In the summer of 2019, a small but combative cricket club from the outer rim of Delhi was in for a great surprise. The girls’ cricket team from Shahabad Dairy in Outer Delhi was meeting none other than Virat Kohli, then the Indian cricket captain. In a swanky hotel in Aerocity, these girls between the ages of 11 and 19 got a once in a lifetime chance to be up, close and personal with the Indian cricket icon.

“How do you manage your team as a captain and how are you able to inspire them to perform at their best and maintain unity in the team?” was the question of 17-year-old Kavita, captain of her side. “You have to treat every team member as equal and support them in their highs and lows,” was Kohli’s answer in a nutshell.

Some players wanted to know how to build innings, while others posed questions on technique and physical fitness. Kohli happily answered them all. The impromptu question and answer session was followed by a well laid out meal. The event, organised and managed by non-profit CRY, concluded with a photo opportunity with Kohli, something the girls were eagerly awaiting.

So, what was so special about this band of girls that they got a chance to spend time with the Indian captain who has such a busy schedule? To answer the question, one needs to rewind to Shahbad Dairy of 2014.

It was the first tough day for the girls as well as their mentor and coach, Santlal, as they toiled for hours, trying to clean up a section of a local park and prepare a temporary cricket pitch. By the evening the pitch was ready and the girls from Shahbad had their first cricket team, all set to play the ‘gentleman’s’ game. The irony in gender representation was hardly missed.

Santlal, who runs Saksham, an NGO that works for education and upliftment of girls in Outer Delhi, had a nightmare building a girls’ team in the area. He would go from house to house, seeking permission from parents to allow their young girls to come and play. Initially he could get only one girl who was allowed. Santlal would do some knocking and other skills practice, with only one girl.

Gradually, after seeing her play in the ground, more girls joined in and finally Santlal was able to muster about half a dozen players.

As the girls started to play, youth from the area gathered around. It was a matter of time before a scuffle broke out as the boys objected to the girls playing cricket on what they claimed was their ground. Santlal had to pull back with the girls as they saw the pitch readied with their sweat and toil getting dug up and strewn with broken beer bottles. In a highly patriarchal society, coming out and playing games like cricket wasn’t a girl’s option. At least, that’s what the boys in the area thought.

Dark alleys of Outer Delhi

Shahbad Dairy is one of the most crime-prone areas in Delhi. Year after year, it registers among the highest rates of crime against women and children. The moment one steps out of the Metro station, one gets drowned in the cacophony of rickshaws and honking motorcycles, jostling for space with pedestrians and stray animals. The maze of narrow lanes is lined by claustrophobic houses built on small patches of land that rise three or four storeys. Most of the residents in the area are daily wage earners, vegetable sellers, masons, and so on. Most of them are migrants from other states, who come to Delhi to seek employment or work. It is a no-brainer that making girls from such a grimy neighbourhood play cricket was always going to be an uphill challenge.

This band of girls started playing various tournaments in Delhi. They also got invited to play in tournaments in Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Telangana

For Kavita, coming out to play cricket was never going to be easy. “I used to get up at 4 am and do all the household chores like washing clothes and utensils, preparing breakfast, and so on. After that I would go to the ground to play cricket and be back by the time my parents woke up. They didn’t even know that I had come back after completing my practice,” she recalls. But her surreptitious cricket outings in the morning were soon busted. “One day, my brother caught me and complained to my parents, yelling how could a girl play a boy’s game. I was locked up and not allowed to play. Somehow, Santlal Sir got to know and spoke to my parents. I don’t know what he said but after that I was allowed to continue playing the sport I loved.”

After persisting for a few months Santlal was able to cobble together a team of a dozen girls, who started practising every evening. Soon, Saksham started providing meals to the girls and assistance with their studies. It was a complete package for the girls. This band of girls started playing various tournaments in Delhi. They also got invited to play in tournaments in Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Telangana. This exposure turned out to be immensely beneficial to the girls as they grew in confidence and became better players. Above all, they developed a keen sense of right and wrong in their society. With time, they started getting media coverage and along the way got the chance to interact with top flight international cricketers such as Kohli, Ishant Sharma and Michael Clarke, to name a few.

With the girls making notable progress in their game, there was a palpable change in their homes and in the neighbourhood. Earning a modicum of respect within their society meant people stopped questioning them about their desire to play cricket. “My brother who used to get angry seeing me play in the ground started going around town proudly with the picture of Virat and me and telling the world this is my sister,” says Priya.

It was a tough day for the girls as well as their mentor and coach, Santlal, as they tried to clean up a section of a local park and prepare a temporary cricket pitch

Cricket and participation

Santlal’s Saksham could be a perfect example of participatory development where sports is used as a tool for social change. According to the International Platform on Sports and Development (IPSD), “Sport for development is about generating social development through the use of sport. It works on three levels: supporting an individual to learn and grow, a community to improve their living conditions, and, in the long term, a nation to overcome conflict or its effects.”

The main aim of Saksham was to get due respect for the children and ensure their rights were honoured. This was achieved locally through cricket. The other big change was that it helped the girls to reclaim their share of public space. Earlier, most of the parks were occupied by boys and it was not possible for girls to play. But as the team grew stronger, not only did it get a chance to play on the same field, it also started getting invitations from the boys to join their team for local matches. Santlal says that the social benefits of the movement became apparent after some time. The biggest change that people of the area started experiencing was the decline in crime against children. “Not only has society started respecting the girl child, the crime rate involving children too has come down in the area,” he says.

2013 ans 2022

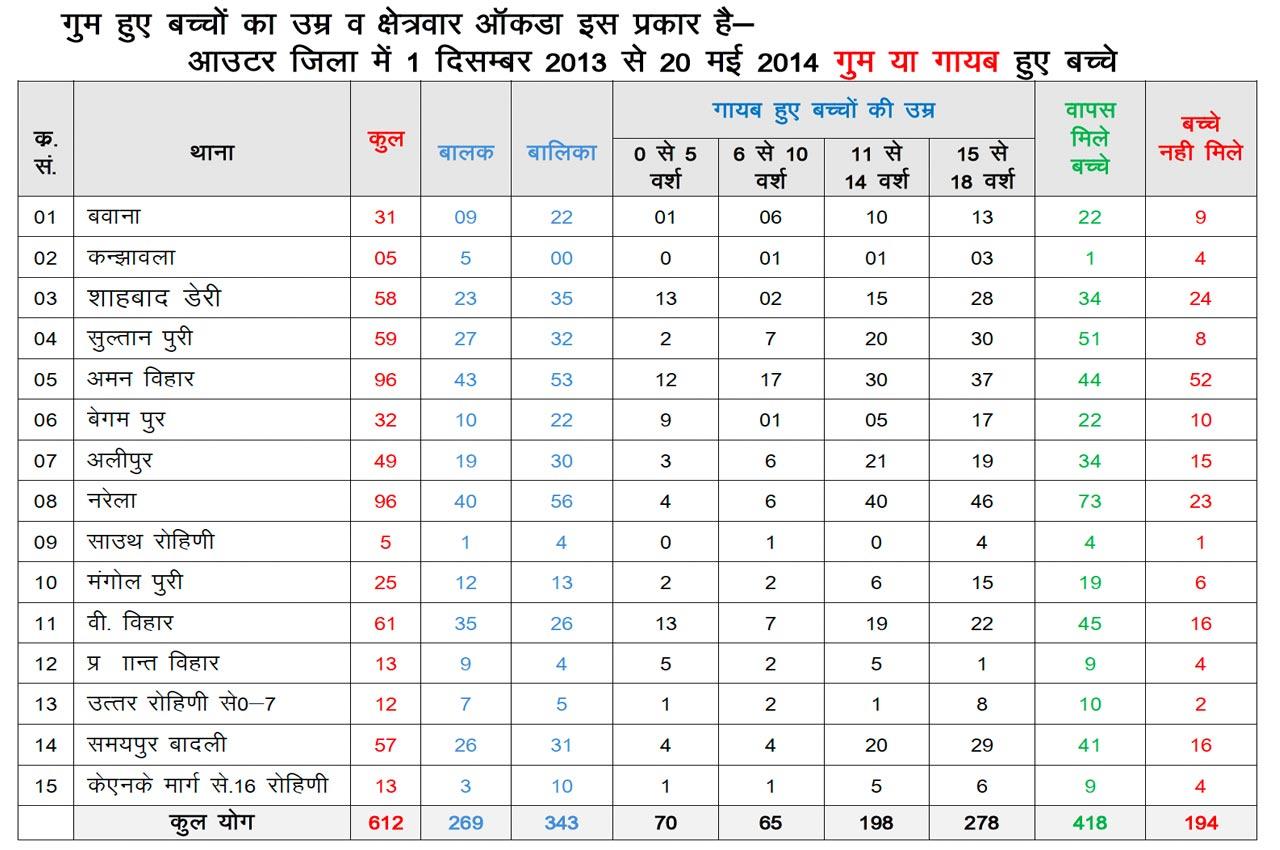

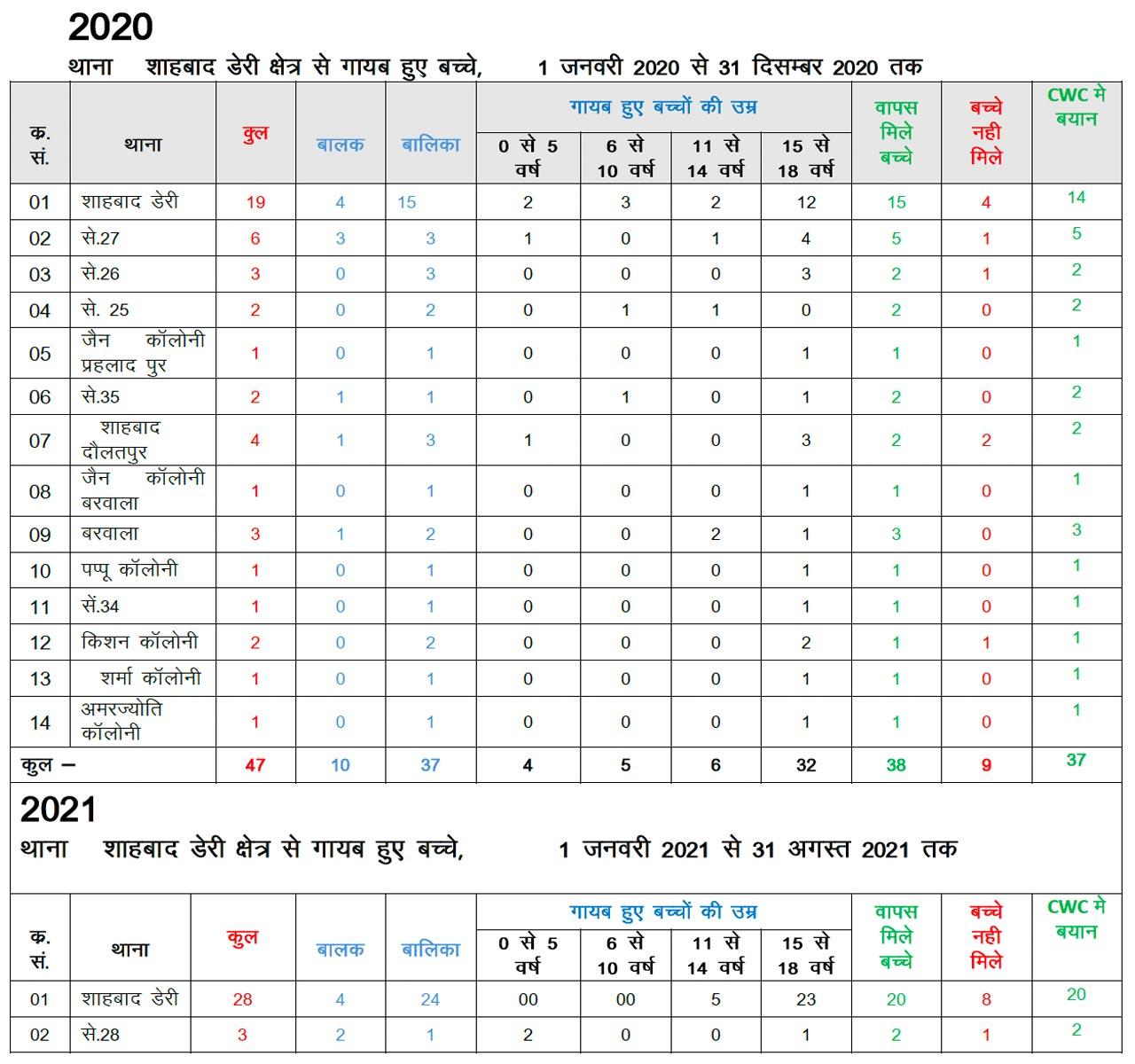

Every year, since 2013, Santlal has been filing an RTI application to obtain information about crime in the area. The downward trend of the crime graph is proof of the social change that the NGO was able to usher in.

For example, the number of children who went missing from Shahbad Dairy between January 1, 2013, and May 20, 2014, was 58, of which 34 never returned or were never found. But by 2020, the number of such disappearances dropped to 19, out of which 16 were traced. Similarly, between June 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015, 19 cases of molestation, rape and attempt to rape of children below 18 years of age were reported; while 15 alleged perpetrators were arrested, four are still at large. However, by 2020 there was a significant drop in the number of rape cases with four cases reported in which all the perpetrators were arrested and convicted under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO).

Santlal attributes this change to two factors. The first and most important is that girls reclaiming public spaces through cricket brought about a significant mindset change among the people, especially young boys, of the area. They are no longer harassed by the boys and can safely move around after dark, which was not possible earlier. The other is that the police became proactive in registering and prosecuting the cases.

Covid changed all

By 2020 the team looked settled in and the girls were getting invitations to play in various leagues and competitions across the country. Society too had embraced their desire to play the sport. Ever since the meeting with Kohli, the girls had gained new respect among their peers, mostly boys. But then the Covid-19 pandemic struck and, like everybody else, the team found its fortunes turning topsy-turvy.

Due to the lockdown and subsequent slowdown of industry, many earning members of the families of these girls lost their jobs. Even after the pandemic ebbed, they were not able to go back to their earlier jobs and their earning capacity took a significant hit. Many of the girls who had played cricket were forced to take up jobs to support their families. “Initially, during the lockdown, we arranged for online classes so that the girls could do their daily exercises and practise a few skills. Later, when we reopened, some of the girls returned but a few were forced to take up jobs in factories or at petrol pumps. The girls who returned to play carried the physical impact of Covid-19, which is reflected in the progress charts that we maintain,” says Santlal. His NGO diligently maintains the progress charts in neat excel sheets for each girl. “We also suffer from a lack of funds. Though we are very thankful to CRY for supporting us throughout and sponsoring a lot of our activities, we are still short on resources for the team to grow as more girls are keen to join our NGO’s team.”

Due to the disruptions caused by the pandemic and the funds crunch, the team could not participate in any tournament. Most of these tournaments have match fees ranging from ₹500 per match to a few thousands, apart from travel and logistics costs. As such, in the current situation, the team doesn’t have the means to pay the participation fees, resulting in their absence from competitive tournaments. “During the pandemic, CRY donated food, medicine and hygiene related items to us, which we passed on to the families of the girls. Later, after two years, we got some money from them and now we have started sending three to four players to play in some tournaments outside Delhi as part of other teams, but we lost two years,” says Santlal.

Another big challenge for Santlal and his girls is that they don’t have a dedicated ground with different types of pitches for practice. “It is still our biggest challenge. It’s a different thing to play on proper pitches and at the nets as compared to a make-do pitch in a park. When our girls go out to play, they face this issue of adapting to proper pitches. When we analyse why we couldn’t do better, most of the time the points raised are that the players couldn’t adjust to the turn and bounce of a true pitch,” says Santlal.

Future prospects

Santlal has high hopes of his girls. He is hopeful that the issue of a proper training ground will be resolved and with that a number of other problems can be taken care of. He says his girls will be more competitive in the age-group trials conducted by the Delhi District Cricket Association and is confident that one of the NGO’s wards will represent Delhi soon.

Another focus area of the NGO is to train the girls in other aspects of cricket so that they are able to exercise different options should they choose to pursue a career in the sport. The NGO also trains the girls in coaching, pitch and ground management, and commentary. Priya has started a new girls’ team in another block of Shahbad, while Kavita is trying to build a team in the Hyderpur area. The idea is to develop a number of teams in the surrounding areas so that they can play amongst themselves.

Due to the lockdown and subsequent slowdown of industry, many earning members of the families of these girls lost their jobs. This forced them to give up cricket

“We want to set examples for other kids in the locality. We want them to change their thinking and behaviour in the same positive manner as we have done. We want to prepare a number of junior teams so that our initiative becomes a movement in the Shahbad area and beyond,” explains Priya.

The girls know meeting Virat Kohli was a high point in their short career so far, but they don’t want to rest there. They want to emulate Mithali Raj, who had a long and illustrious career with the Indian women’s team. “My aim is to play for India one day,” says Kajal. For most of the girls, cricket is more than just a sport, they see it as a path to becoming better human beings.