Nirmal Prajapat from Churu, Rajasthan, claims that farmers like him face an uphill task when claiming the amount payable to them under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY). In most cases, he says, they are forced to resort to protest demonstrations to secure compensation even as the vagaries of nature continue to destroy standing crops. Avinash Kumar, a farmer from Bihar’s Nawada district, complains of phone connectivity problems in his area, making it extremely difficult for farmers to inform the nearest agriculture officer or the nearest CSC Centre via a call or through the Crop Insurance App within 72 hours of suffering crop damage as mandated by the scheme. Others point out the difficulty in operating the app to file intimation of crop damage within the stipulated period.

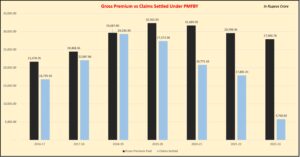

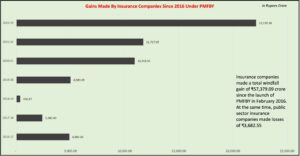

Meanwhile, insurance companies are raking in huge windfall gains with claim disbursement consistently falling over the past few years (see Graph 1), according to government data placed in Parliament during the Monsoon Session.The gains made by insurance companies increased from less than ₹5,000 crore in 2019-20 to a whopping more thanr ₹22,000 crore in 2022-23 (see Graph 2). Since February 2016, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his showpiece scheme for the agriculture sector, insurance companies have raked in a whopping windfall of ₹57,379.09 crore. In other words, the insurance sector has made gains in excess of 350% in the past seven years.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare (MoAFW), 20 general insurance companies, including five public sector units, have been empanelled by the Government of India for the implementation of PMFBY. A ministry statement added that “specific insurance company is selected by the concerned State Government through a transparent bidding process”.

In the written answer tabled in Parliament in July, the ministry stated that the public sector general insurance companies are the Agriculture Insurance Company of India Ltd (AIC), National Insurance Company Ltd (NIC), New India Assurance Company Ltd (NIA), Oriental Insurance Company (OIC), and United India Insurance Company Ltd (UIIC). The private sector players include Bajaj Allianz, HDFC ERGO, IFFCO-Tokio, Reliance General, ICICI Lombard, Universal Sompo, Royal Sundaram, Chola MS, Future Generali, SBI General, Shriram General, TATA AIG, Go Digit, Kshema, and Raheja QBE. Of these, private players like Shriram General and Royal Sundaram have significantly scaled back their operations.

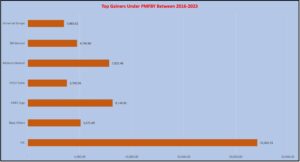

Between 2016 and 2023, AIC topped the list of gainers, followed by HDFC ERGO and Reliance General (see Table 3). Some farmers might have benefited from PMFBY since it was launched in 2016, but a clutch of private insurance companies and a couple of public sector operators have benefitted the most. Official data suggests that in the past seven years, insurance companies have collected premia worth ₹1,97,657 crore and paid out ₹1,40,036 crore to farmers in claims. The total collection as gains works out to approximately ₹57,379.09 crore.

Interestingly, the data also shows that public sector insurers have picked up the bulk of losses. They paid out more claims than premia collected. Oriental Insurance racked up losses of ₹2018.17 crore, while New India Insurance’s losses amounted to ₹1,499.31 crore and National Insurance lost ₹165.07 crore. Explaining this peculiar skew, farmer-activist Ramandeep Singh Mann says, “Most of the private players have very high-quality data of long-term risks of crop damage and weather patterns at the block level. They bid for blocks (regions) where the weather is not erratic, say, Patiala or Ambala. They identify the risk-free blocks.”

PMFBY only covers food crops (like cereals, millets, and pulses), and oilseeds and some commercial and horticultural crops, subject to certain parameters. It is the concerned state government that is responsible for the assessment of crop damage and the insurance companies then make the payment.

For crops not meeting the parameters, the state is free to notify them for coverage under the Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) for which payment of claims is being structured on the basis of weather index parameters.

For example, the Himachal Pradesh government is notifying apple crop under RWBCIS. Being a central sector scheme, state-wise allocation or release is not made under PMFBY and RWBCIS. Funds are released to the central fund routing agency (AIC), which in turn releases the central government’s share in premium subsidy on receipt of respective state government’s share, to the concerned insurance companies. The scheme involves so many separate players that several claims are awaiting disbursal, ranging from between two years to six months, as reported by Tatsat Chronicle recently.

The government says that to resolve complaints over unpaid or delayed claims, the Stratified Grievance Redressal Mechanism has been put in place. The layers of the dispute resolution involve District Level Grievance Redressal Committee (DGRC) and State Level Grievance Redressal Committee (SGRC) under the Revised Operational Guidelines of the scheme. The concerned state governments can also take suitable punitive action against defaulting insurance companies. But it appears that farmers like Prajapat and Kumar have to run around in circles to get their claims.

In August 2021, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Agriculture recommended action against defaulting insurance companies “so as to make sure that the whole process of penalisation is completed within a fixed timeframe”. It also suggested that a timeline be fixed for the companies to settle claims and “in case of non-adherence to the timelines the insurance companies be penalised”. It also added, “when the reason for delay is non-payment of subsidy by the state, the premium paid by the farmers be returned along with interest within a fixed timeframe”.

When this Standing Committee sought to know if any insurance companies had been penalised, the agriculture department officials said Chola MS, ICICI Lombard, New India Assurance Company and State Bank of India General Insurance were fined for the rabi season of 2017-18. The cumulative fine worked out to around ₹22.17 crore. Yet, most of the pending claims are weighed under layers of disputes and red tape. Not many companies have been pulled up for failing to settle claims in reasonable time.

The government also claimed that to better resolve grievances and complaints, a portal and a Unified Krishi Rakshak Helpline have been developed. “The beta version of the portal was launched in Chhattisgarh on July 21, 2022,” Narendra Singh Tomar, minister for agriculture and farmers’ welfare, informed the Rajya Sabha on July 21. But will it help farmers get quick compensation, because the fundamental problem of poor connectivity in large parts of rural India remains, is the question.

The All-India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), one of the leading farmer unions, says that privatisation of crop insurance through PMFBY has resulted in taking crop insurance out of the purview of public regulation. “While insurance companies have been made the main vehicle for providing crop insurance, the government has created no regulatory mechanism to ensure that the insurance companies and other private agencies involved in the process do not indulge in any malpractice,” it said in its resolution.

Where do funds come from?

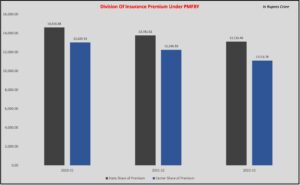

Under the PMFBY, farmers have to pay a nominal 2% of the sum insured as premium in kharif season and 1.5% for the rabi crops and 5% for cash crops in both seasons. The rest of the premium is shared equally by the central and state governments. Thus, a major part of the premium is borne by the tax-payer (see Graph 4). Another aspect that has raised concern among farmer unions, irrespective of their political affiliations, is the provision for adjusting disaster grant amounts in the PMFBY. Opposition-ruled states have urged the Centre to amend the rules issued in October 2022 to end the inclusion of assistance given to farmers from the State Disaster Relief Fund for crop damage.

They argue that diverting disaster grants defeats the whole concept of crop insurance and drains the fund meant for relief and sometimes rehabilitation in case tragedy strikes elsewhere. In addition, farmers are only protected when losses are incurred by a large numberof them in the area.

The unions argue that crop losses mostly occur because of localised problems affecting individual farmers such as invasion by wild and stray animals, pests and disease attacks, disadvantageous crop terrain, poor drainage and irrigation facilities, and differences in crop schedule. No crop insurance is provided to such farmers who suffer crop losses individually, they say.

The scheme has been reviewed periodically for improvement, but the latest data shows that it needs a major revamp if it is to provide adequate compensation to farmers, who bear the maximum risks and losses. When Modi launched the PMFBY on February 18, 2016, he blamed the previous UPA governments for failing to improve the lot of farmers and promised that the scheme would play an important role in doubling their income by 2022. However, a cursory look at the data reveals that the average monthly income of farmers in India is a mere ₹10,218 with wide variations from state to state. For example, in Punjab the average monthly income is ₹26,701; in Meghalaya it is ₹29,348; in Jharkhand it is ₹4,895. Meanwhile, PMFBY is helping the insurance companies, especially the private sector ones, to fatten their bottomline.

(With inputs from Vivek Mukherji)