Much before the urgency of transitioning to renewable energy dawned upon us to combat global warming and climate change, the idea of harnessing the sun to generate electricity had taken root in a small village called Tilonia, about 50 km northeast of Ajmer in central Rajasthan. In a little over a quarter of a century, the idea has assumed impressive dimensions.

The beginnings were modest, but its subsequent worldwide impact shows that a community-based model to adopt solar energy can be as successful, if not more, as mega solar power projects, covering thousands of acres of land, that are funded by the government and aid agencies. Initially, the experiment of installing solar power systems was limited to Tilonia, but serious efforts to scale it up began in 2000.

Since then, the women of the village, who lacked formal education, overcame age-old social taboos and stereotypes to end up helping to set up an astounding 1.4 gigawatts (GW) solar power generation capacity in thousands of villages across the world

Since then, the women of the village, who lacked formal education, overcame age-old social taboos and stereotypes to end up helping to set up an astounding 1.4 gigawatts (GW) solar power generation capacity in thousands of villages across the world. The immensity of their achievement can be grasped when this is compared with the fact that just 46 GW was added to India’s renewable energy capacity in the same time frame with the combined efforts of the government, aid agencies, and private companies.

The Tilonia experiment is not just about the physical production of renewable energy, but also about arming underprivileged sections of the population with the self-confidence to solve their own problems. About half a million villagers in 96 countries, who had remained outside their national grids, are now able to access electricity to light up their homes and cook by implementing this unique model of self-sustenance. Significantly, backup after-sales service was provided at their doorstep by one of their own.

They discovered that a bottom-up approach instead of a top-down one would work better in India, but the professed experts in the field at that time differed with Roy and his fellow travellers

Humble origins

The uniqueness of the programme is that it was led not by electronics engineers trained at leading technology institutes but by barely educated women who had learnt to handle advanced technologies like integrated circuits, condensers, diodes, multi-meters and printed circuit boards with great dexterity through the unique ‘barefoot’ method of training. Approximately 3,000 women in India and abroad, styled as ‘solar mamas’, have managed this feat at an unbelievably meagre cost of $15 million. The ‘barefoot’ solar engineers have learnt to set up solar cookers and heaters alongside.

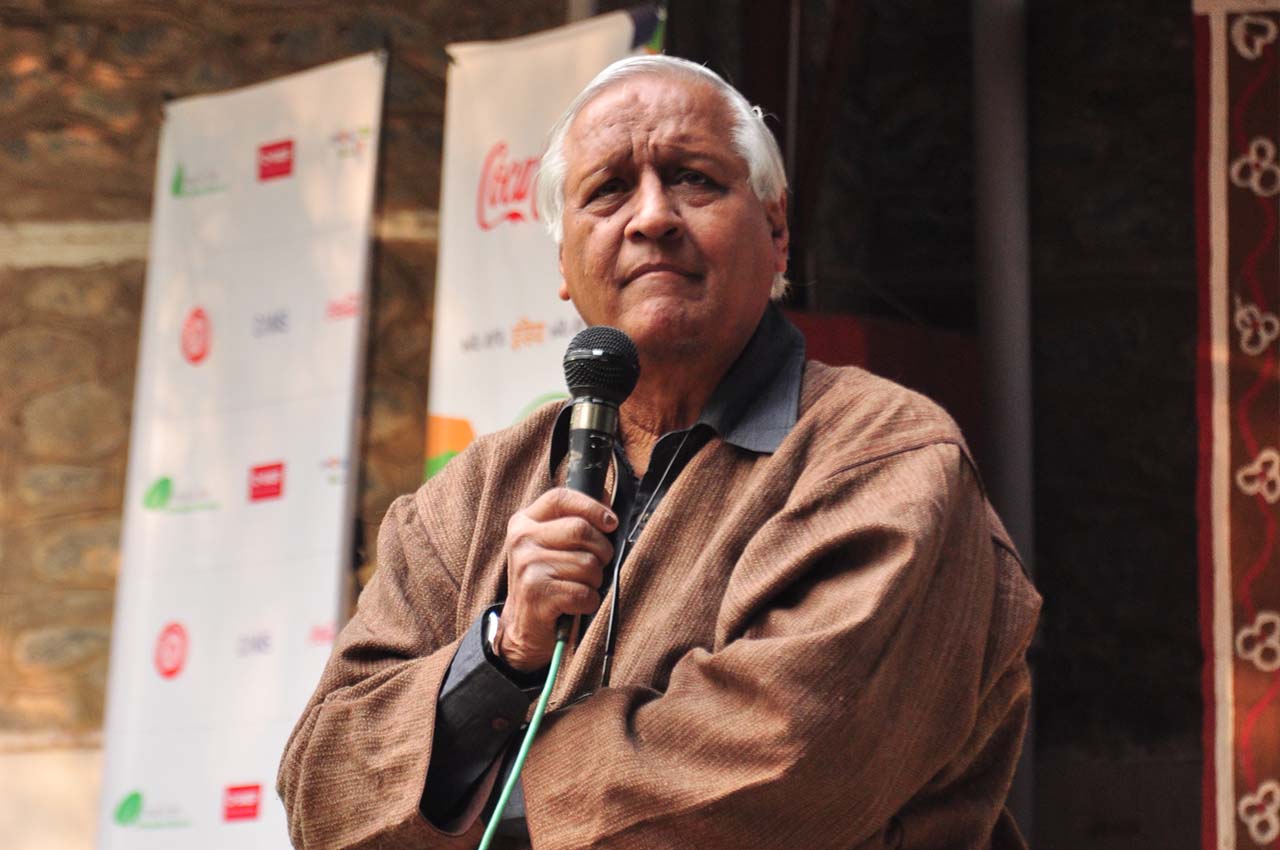

The secret of this success belongs to what has come to be known as the ‘Barefoot College,’ formally known as Social Work Research Centre (SWRC), founded in 1972. The moving spirit behind the college is Sanjit ‘Bunker’ Roy, who gathered a band of idealistic, highly-qualified ‘crazy but daring’ friends who set out for the rural hinterland to discover alternative models of development after finding that the urban-centric efforts were failing to deliver benefits where they were most needed. Just out of college, these youngsters were disturbed by the stark contrast between their own privileged lives and the abject poverty in which a majority of Indians were mired.

In the early days, the founders of the Barefoot College did not set out with any clear plan or idea since they did not know the answers to solving the problems of rural people. They came up with solutions as they went along. In the early ’70s, Roy learnt the ways of the rural people, assimilating their indigenous knowledge and skills from his farmer friend, Meghraj. This led to the realisation that the way forward was harnessing the traditional knowledge of the rural people and combining it with modern techniques. The key was instilling a sense of participation, community ownership, and asset management among the people of rural India.

They discovered that a bottom-up approach instead of a top-down one would work better in India, but the professed experts in the field at that time differed with Roy and his fellow travellers. According to Roy, the big mistake that international development agencies make is believing that professionals from outside will be able to solve the problem better. “That isn’t the case…it cannot happen. Take the community into confidence and let them manage it, control it, and own the process….that is the way forward. Billions have been spent by experts and engineers, but they have not been able to provide clean, inexpensive and non-polluting electricity to millions across the developing world. But they still haven’t learnt,” says Roy.

Though most of his friends dropped out, succumbing to parental or peer pressure for settled lives and regular jobs, Roy persevered and has completed half a century in this remote Rajasthan village, helping the local community solve its problems by combining modern technology with traditional skills. In the initial days, the urban youngsters led by Roy weren’t exactly welcome in the villages and were viewed with a degree of suspicion, being suspected of being agents of Christian missionaries whose real aim was conversion.

Roy’s persistence eventually overcame their scepticism. “The biggest challenge I faced was convincing people that it was possible for an illiterate man or woman to be anything—architect, solar engineer, communicator, designer,” recalls Roy, who got his nickname ‘Bunker’ from his habit of skipping classes. “If what you do benefits the community, you can certainly win their confidence,” he said in an interview recently.

Roy adopted a Gandhian approach to build what became well known as the Barefoot College— a concept borrowed from the barefoot health workers of China, who were villagers trained to work among rural communities in the 1960s. The central idea was self-reliance and the use of sophisticated technology in rural areas on the condition that control should remain in the hands of the poor communities. The campus, therefore, was set up in a rural area of Rajasthan on a 45-acre plot of government land and 21 buildings of an abandoned tuberculosis sanatorium were leased in 1972 at ₹1 a month. At that time, the population of Tilonia was just 2,000.

Model of empowerment

According to the SWRC website, the Barefoot College (not to be confused with Barefoot College International) is a space “where the poor, the deprived, and the dispossessed feel that they can talk and be heard with dignity and respect, be trained and given the tools and the skills to improve their own lives”.

Explaining the reason behind the use of the term Barefoot College, Roy says that millions of underprivileged people in India, who pass on the knowledge, skills, and wisdom of their forefathers, live and work barefoot. They sit and work on the floor. “It is symbolic of the importance that we give to the collective knowledge and skills that rural communities have. It is far more valuable than any paper qualification…the biggest challenge I faced was to convince people that it was possible for an illiterate man or woman to be anything….one does not need to be literate to be able to provide these professional services. You do not need to go through a formal university to have the skills and the experience to provide the service to communities,” he says.

Though the college has produced barefoot professionals like health workers, midwives, dentists, teachers, water conservation experts, architects, masons, mechanics and artisans, it attained worldwide fame through its solar power training programme. It has been so successful that in 2011 the Dalai Lama, during his visit to the campus, said, “Now that you have shown the Barefoot College working in practice, let us see if the experts can make it work in theory.”

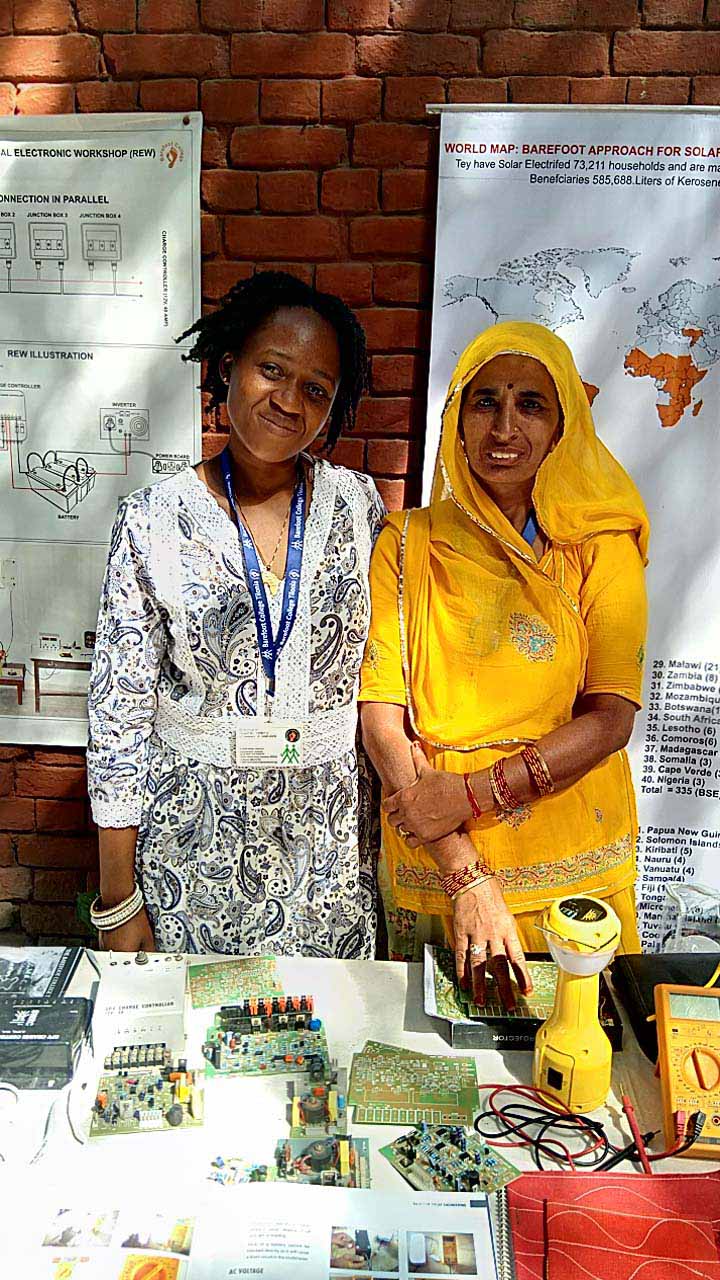

Earlier this year, an exhibition-cum-sale of clothes, crockery and decorative items made by the villagers of Tilonia was held at the Shriram Kala Kendra in Delhi. The villagers manufacture these items to supplement their incomes. But it was the hi-tech items such as home solar lighting units consisting of four lamps, a solar panel, and accompanying hardware and software to run it that drew the maximum number of visitors. Looking at Magan Kanwar, a 50-year-old woman from Bawdi village in Tilonia who gave the demonstration for operating the solar unit, one would be hard-pressed to believe that she carries the designation of ‘solar professor’ and trains women with little formal education about the intricacies of deploying the system around the world. She has travelled to Mexico, Fiji, Senegal and a host of African countries, evangelising the use of solar energy at a micro level.

At the exhibition, standing next to Kanwar, was her pupil, Catharine Matimba, from Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Though Matimba, a scholar at Pondicherry University, can hardly be called illiterate, she is training under Kanwar to become a ‘solar mama’. She says that her background in research will give her the ability to study the impact of the solar energy programme of the Barefoot College in her native Zimbabwe and other African countries. The trained women have appropriately been given the nickname of ‘solar mamas’ by no less a person than Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

These ‘solar mamas’ form the backbone of the solar energy programme of the Barefoot College, which has helped to provide electricity to remote regions of the world. The programme started in 2000, a good decade and a half before the formulation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the UN. Unlike most major government programmes, it meets all sub-goals of SDG 7. “It’s not mass production but production by the masses,” says Roy.

Though, while promoting the SDGs, the UN emphasises the involvement of people in the use of energy from clean sources, governments continue to adopt a top-down command approach and choose the easiest path to the targets without bothering too much about the risks to lives, livelihoods and ecosystems that their “solutions” might pose. India, for example, promised at the recent Glasgow Conference on Climate Change that by 2030 it would reduce carbon emissions by a billion tonnes and meet half its energy requirements from renewable sources, but the roadmap for achieving this target is not clear.

Roy adopted a Gandhian approach to build what became well known as the Barefoot College— a concept borrowed from the barefoot health workers of China, who were villagers trained to work among rural communities in the 1960s