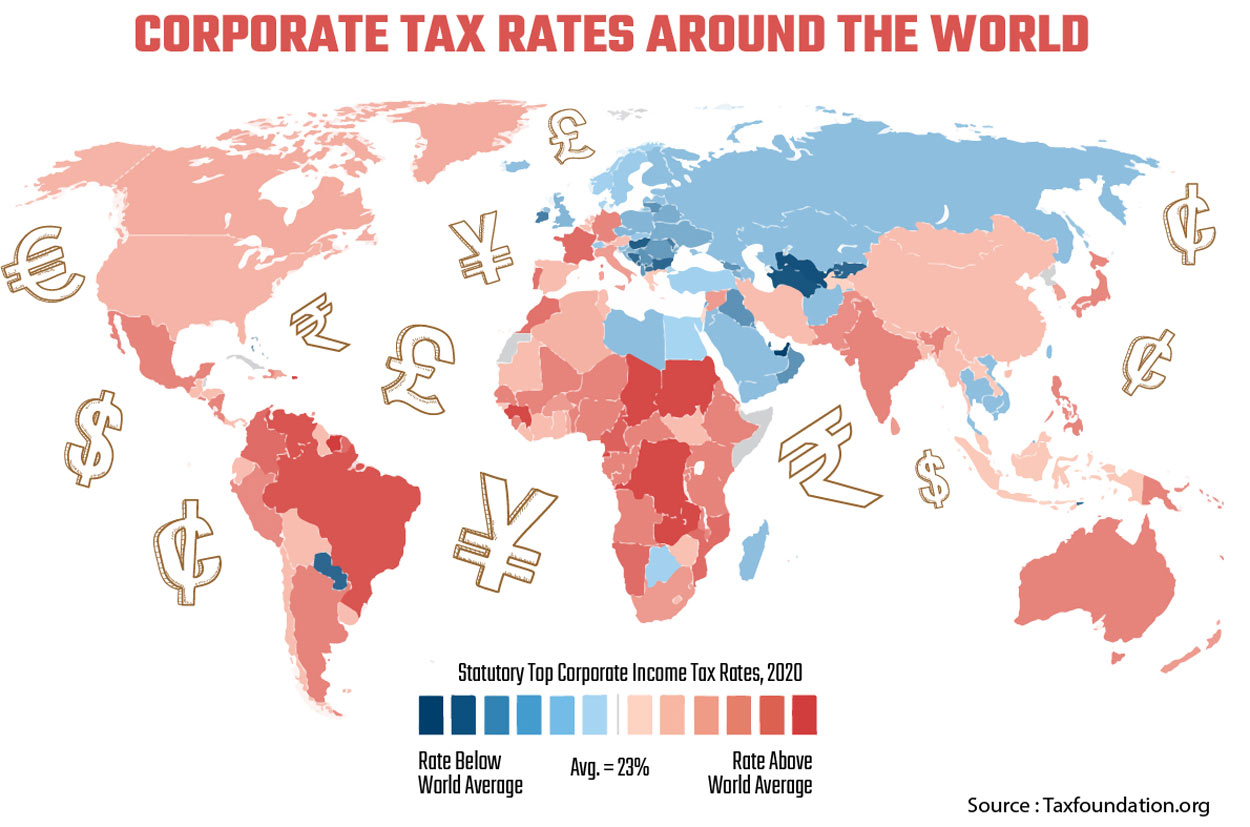

When Janet Yellen, the US Treasury Secretary, suggested in April this year that it was time to impose a global corporate tax on multinationals to end the ‘race to the bottom’, very few would have said that matters would move ahead with such speed. But, in quick succession, finance ministers from the group of G7 countries, a club of the richest, gave backing in June to a ‘minimum’ rate of 15 percent global corporate tax, followed by a green light from the G20 group — where global tax matters are discussed — comprising India, China and Russia. That approval provided the incentive for the larger group of countries, 136 of whom have given their assent in the matter at last count.

India was a last-minute signatory, with Brazil, Ireland and China agreeing to the deal reluctantly. Ireland okayed it after others agreed to change the “minimum” tax norm to “maximum” tax. China came on board only after an agreement to limit the impact of the new norms on companies which are beginning to expand globally-thus protecting its upcoming domestic companies.

Many called it a ‘tax revolution’, bringing to heel the top global corporates by forcing them to pay 15 percent in taxes on profit, changing the practice for decades when many of them could get away by paying zero or low taxes. This they could do by locating or relocating to jurisdictions where taxation is low or non-existent.

So, why did the majority of the world’s countries come around to taxing the big daddies of the corporate world?

Two-pillar rule

An estimated $500 billion in tax is avoided by global corporations and their subsidiaries by taking advantage of the legal avenues available to them. Tax avoidance is legal, in contrast to tax evasion which is illegal. The changes being brought about are basically two-one, to allow countries to tax on the basis of economic activity instead of where companies choose to book profits; and two, set a threshold level of tax (Global Anti-Base Erosion or GLoBE). This is known as the ‘two-pillar rule’ of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project.

That means that a company that markets its product in, for example, the United States would have to pay a proportion of the tax there, instead of, say, in Ireland where the company is headquartered, attracted by its low (12.5 percent) corporate tax rate. The larger effort is against the tax havens which offer zero or very low rates of taxation, benefitting from the fees and presence of thousands of lawyers and tax consulting firms who bring in employment and revenue.

Large economies where multinationals sell their goods and services stand to benefit the most with some of the money going to poorer countries where the companies have set up factories because of low labour costs. A global study three years ago found that more than one-third of the global companies have shifted their profit-taking to low-taxation countries.

An estimated $500 billion in tax is avoided by global corporations and their subsidiaries by taking advantage of the legal avenues available to them.

Giants like Apple and Google have also chosen to take advantage of the competitive approach to taxation by several countries. Google alone may have benefitted by tens of billions of dollars over the years by sending profits of subsidiaries to a jurisdiction like Ireland while being registered in a country like Bermuda, according to The Economist. Fair Tax Mark, a British tax-reform advocacy group, estimated that the top six companies based in America’s Silicon Valley paid $155 billion less in taxes in the US in the decade beginning 2010.

According to tax haven expert Nicholas Shaxson, writing for an International Monetary Fund (IMF) publication, the US Fortune 500 companies held around $2.6 trillion in offshore jurisdictions in 2017 although the US tax reforms in 2018 reduced this by a small amount. The corpus held abroad has increased steadily because of changes in the law and higher level of taxation at home. In the 1990s, between five and 10 percent of US multinationals held money in tax havens. This had gone up to 25 to 30 percent till recently, according to a study.

The 2008 global financial crisis first drew major attention towards multinationals stashing money in low-tax jurisdictions. The US and other Western nations started looking at global laws and how to bring home the avoided tax. In 2018, the US learnt that Swiss bankers had helped US corporations evade tax. Instead of putting pressure on the country, the US went after the bankers and banks. This resulted in Switzerland agreeing to share information on their accounts.

In March 2019, Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, called for a fundamental rethink on low-tax jurisdictions. In May 2019, the OECD published a road map on the “two pillars” approach which was highly radical. But once the US put its weight behind the move, other countries followed in what is being termed as the ‘most significant’ change in global corporate taxation in a century.

The Panama Papers in 2019 (and the Pandora Papers in October this year) have brought about a substantial change in public thinking about how tax havens have been used for nefarious purposes. Governments have ridden on this wave of derision to agree to the OECD proposal on taxing global corporations. Already, efforts by OECD’s 38 countries and the G20 have yielded information from 90 countries and 47 million accounts, resulting in tax collection of 95 billion euros, without the benefit of the new law.

India and Global Corporate Tax

Like most other nations, India would have to amend its law on taxing multinationals which do business here or are headquartered in the country. Unlike the OECD nations, India does not have provisions in its income tax laws on a Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) under which passive income like capital gains, interest, dividends or royalties were traditionally taxed. Such CFC provisions were included in the Direct Taxes Code Bill presented in Parliament in August 2010 which lapsed.

According to Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India, part of the global tax consultancy, the average yearly outward foreign direct investment from India was more than $9 billion in the past two decades, largely regulated through foreign exchange regulations. The lack of CFC provisions may come in handy for India in as much as anti-avoidance legislation can be passed without being encumbered by an existing law that may need amending or repealing.

The income tax law in India does have taxation provisions for subsidiaries of Indian companies or those controlled by persons located in the country. An incentive is built into the law for Indian parent companies by taxing them at a lower rate than domestic companies for receiving dividends from foreign subsidiaries.

Additionally, a sort of anti-avoidance rule does exist in the provision on the Place of Effective Management. The global income of a company becomes taxable in India if the effective control and management of such a foreign company is in India. Because its decisions are taken in this country, a company incorporated abroad becomes tax resident in India.

These provisions would have to be incorporated into the changes which would have to be brought about because of BEPS requirements, after wide consultation with the stakeholders. Once the changes are in place, India’s treaty countries with low taxation, like Mauritius and Singapore, are also likely to feel the heat. –H.S.

Attractive options

Tax havens in the Caribbean offer very low to nil taxation, attracting some of the world’s top corporations. Others like the British Virgin Islands or Cayman Islands offer competition to them, while jurisdictions like Hong Kong, Singapore, Ireland or Cyprus compete with them via modern and efficient economies with low taxation.

Fair Tax Mark, a British tax-reform advocacy group, estimated that the top six companies based in America’s Silicon Valley paid $155 billion less in taxes in the US in the decade beginning 2010.

The proposed taxation is likely to affect the business of the zero or very-low taxation more than the moderate taxation ones, but most would feel the pinch. They would have to rejig their business models-some of them get almost two-thirds of their revenue from taxation related matters-or go out of business. Luxembourg, a small nation nestled among big economies in Europe, attracted more than 10 percent of the global foreign direct investment, according to the IMF. This bonanza may be about to end.

Tax havens have existed for a very long time. People have always wanted to hide their income from governments. Among the oldest ones of modern times, dating from 1920, are Lichtenstein, Switzerland and Panama. Apart from low or nil taxation, the havens zealously guard the personal financial information of their clients. They have legal or administrative practices to prevent scrutiny. Further, they do not insist on any local presence. You can buy a shell company in a tax haven by merely naming a consultant locally. In the end, they are marketing enterprises, trying to attract business from high-taxation countries.

The Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), set up in 1961 to stimulate world trade and economic progress, estimates that government incomes could increase by $150 billion once the new rules kick in, possibly by 2023. Additionally, $125 billion of profits could be reallocated to be taxed where the big companies generate revenues but may have little presence.

Among the oldest tax havens of modern times, dating from 1920, are Lichtenstein, Switzerland and Panama.

The multinationals would benefit from a rule which enjoins on the countries agreeing to the new taxation not to impose new digital services taxes and repeal some existing ones. Top digital companies have been raising voices against such taxes in Europe. According to the OECD, Pakistan, Kenya, Nigeria and Sri Lanka have not yet signed up for the deal. Kenya and Nigeria said they did not get enough compensation under the new deal despite its call upon all countries to withdraw their existing digital service taxation.

- $500 billion tax avoidance per year (IMF study)

- $2.6 trillion held offshore by US Fortune 500 companies

- 30% of US multinationals have offshore holdings

- $8.7 trillion to $36 trillion held by individuals offshore

- $10.3 billion lost by India every year to tax avoidance

The European Union is likely to come up with a model law on the BEPS, but each country would have to pass the bill or ratify it in their national legislature. Yellen has urged the US Congress to swiftly pass the proposals by taking the reconciliation route which allows bills to pass the Senate with a simple majority. However, the Republicans have said they would oppose the move which has been called a once-in-a-generation proposal by the Democrats.

The OECD has aimed for such legislation to fight tax avoidance for years, without success. OECD officials said the deal would make the international corporate tax system “fairer and better”, calling upon countries to ensure effective implementation of the reform. The deal would make the largest multinationals with a turnover of more than 20 billion euros to be required to allocate 25 percent of their profits, in excess of a 10 percent margin, to countries where they market their products. The rules on corporate taxation would apply to all multinationals with a turnover above $750 million.

As mentioned, the impact of the BEPS would be the strongest on countries with low- or no-taxation policies. They would have to bring in legislation to bring the level of taxation in conformity with the new rules or see the money being taken away from the multinationals by other countries.

Government incomes could increase by $150 billion once the new rules kick in, estimates OECD.

Apart from the money held in offshore accounts by multinationals, an estimate by the University of California, Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman shows that as much as $8.7 trillion may be in these accounts abroad belonging to individuals. Another economist puts the figure at $36 trillion. After the countries have brought the multinationals within the tax nets, they are likely to look at this larger stash of money, often ill-gotten gains being hidden in tax havens, sometimes belonging to leading politicians, as shown by the Panama Papers leak.

It is possible that some of the low-taxation countries chose not to take a decision to change their laws. But the very nature of BEPS would work against their interests with the consequence that the money they have made by offering tax competition to the big countries may do a quick vanishing trick. The halcyon days of tax havens may just be coming to an end.

(Hardev Sanotra is a freelance journalist based in Delhi-NCR)

By Hardev Sanotra