One hundred and ninety-three member states who have adopted Agenda 2030 of the United Nations, including India, need to get their act together fast if they intend to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and 169 targets defined under them, by the end of the decade. Two recent reports—one by the United Nations Economic and Social Council and the other published in Nature journal—suggest that most of the countries are way off-course in achieving the stated goals as we approach the halfway point since they were first adopted in September 2015.

In fact, the import of the paper published in Nature on June 20, 2022, goes to the extent of predicting that the SDGs are doomed to fail for a number of reasons. The UN’s latest progress report paints an equally grim picture. “Today, we stand on the precipice of a critical moment. Either we fail to deliver on our commitments to support the world’s most vulnerable or together we turbo-charge our efforts to rescue the SDGs and deliver meaningful progress for people and the planet by 2030—stepping up our work to transform the international financial architecture; driving major economic transitions and renewing the social contract, and investing in data systems,” says the UN’s latest progress report.

The two primary factors identified by the UN that have reversed decades of progress are the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that has sent massive shockwaves and disrupted the global supply chain of foodgrains. With Russia blocking Ukraine’s Black Sea port, export of millions of tonnes of wheat and other foodgrains from the beleaguered country has virtually come to a standstill.

The impact of the pandemic has been particularly devastating, upending years of progress. “Global health systems were overwhelmed, and many essential health services were disrupted, posing major health threats and undermining years of progress fighting other deadly diseases,” says the report.“Furthermore, an additional 75 million to 95 million people will live in extreme poverty in 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic level. Billions of children significantly missed out on schooling and over 100 million more children fell below the minimum reading proficiency level and other areas of academic learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of $17 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value.”

The war in Ukraine has triggered an unprecedented refugee and food crisis, which will have a long-lasting effect on the SDGs. “As of April 2022, more than 5.3 million refugees had fled Ukraine (most of who are women and children) and a further 7.7 million had been displaced inside the country. Another 13 million were stranded in conflict areas. Added to this, Russia and Ukraine are large producers and exporters of key food items, fertiliser, minerals, and energy. These two countries represent more than half of the world’s supply of sunflower oil and about 30% of the world’s wheat. At least 50 countries import at least 30% of their wheat from Ukraine or Russia, with 36 importing at least 50%, and most of them are African and least developed countries.”

The closure of schools due to the pandemic has had a severe impact on SDG 4, which focuses on ensuring quality education and lifelong learning for all. “The COVID-19 outbreak has caused a global education crisis. Most education systems in the world have been severely affected by education disruptions and faced unprecedented challenges. School closures brought by the pandemic have had devastating consequences forchildren’s learning and wellbeing. It is estimated that 147 million children missed more than half of their in-class instruction over the past two years. This generation of children could lose a combined total of $17 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value. School closures affected girls, children from disadvantaged backgrounds, those living in rural areas, children with disabilities and children from ethnic minorities more than their peers,” notes the latest report.

The two primary factors identified by the UN that have reversed decades of progress are the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

On gender equality, the report clearly states that the “world is not on track to achieve gender equality by 2030”. Though the pandemic has worsened the situation, chronic failures like policy implementation, weak laws and other systemic flaws remained unaddressed even before the global emergency. “Over 100 million women aged 25-54, with small children at home, are out of the workforce globally in 2020, including the more than 2 million who left the labour force due to the increased pressures of unpaid care work. Women’s health services faced major disruptions and undermined women’s sexual and reproductive health. And despite women’s effective and inclusive leadership in responding to COVID-19, they are excluded from decision-making positions.”

The peer-reviewed paper published inNature—for which 61 scholars analysed 3,000 scientific studies—concluded that “the goals have had some political impact on institutions and policies, from local to global governance. This impact has been largely discursive, affecting the way actors understand and communicate about sustainable development. More profound normative and institutional impact, from legislative action to changing resource allocation, remains rare” and had “limited transformative political impact”.

Interestingly, even as discussions around the SDGs continue to gain traction at various forums and levels, researchers have suggested that they have not found any substantial evidence that adoption of the goals has “advanced the position of the world’s most vulnerable countries in global governance and in the global economy”. The evidence on record highlights that the global legal and policy frameworks have not been altered that will allow such countries to have a greater say in global governance. However, on the brighter side, adoption of the SDGs has given a tool to civil society organisations to hold their governments to account, which to some extent has led to affirmative action on the ground.

On gender equality, the report clearly states that the ‘world is not on track to achieve gender equality by 2030’. The pandemic has worsened the situation

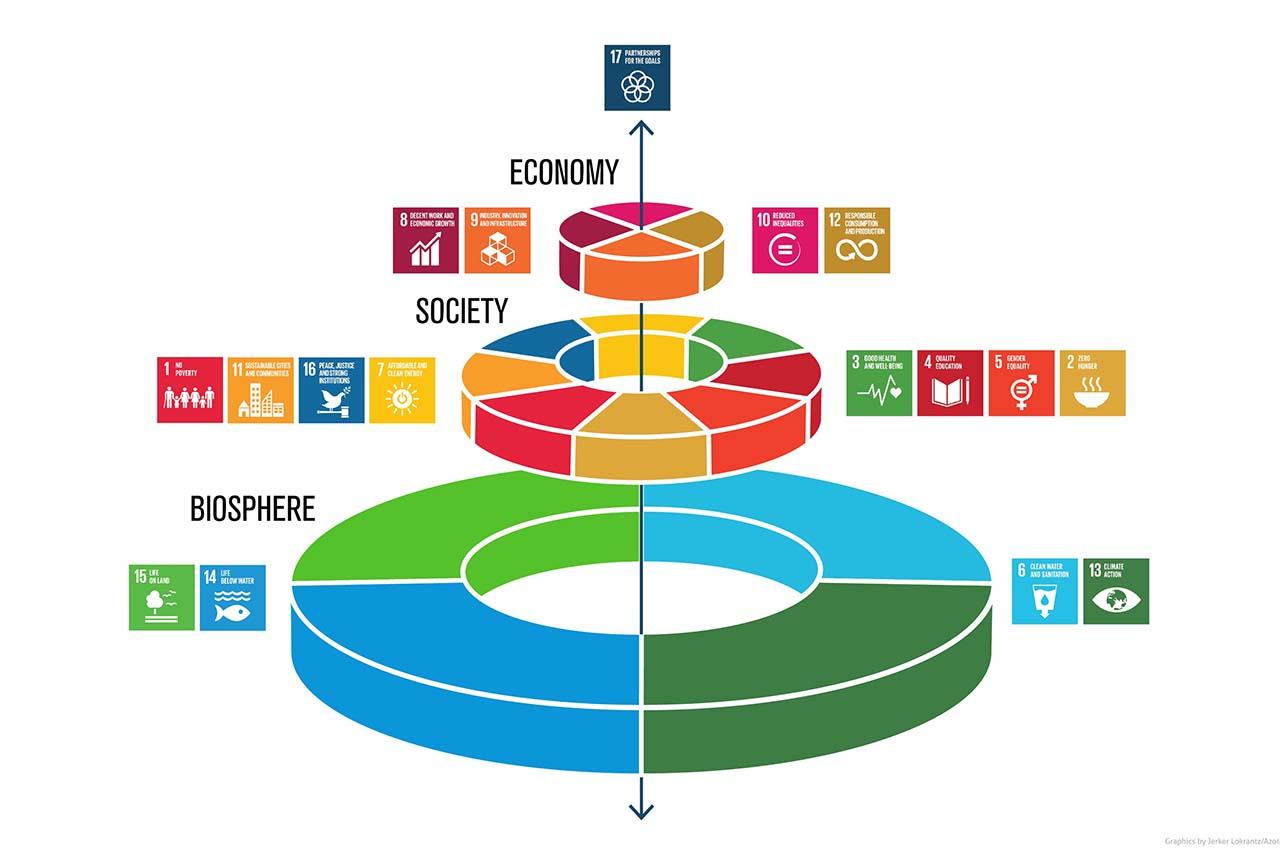

The authors of the paper have put the spotlight on some of the inherent contradictions that are built into these goals. The primary aim of the SDGs when they were framed was to ensure the long-term sustainability of life on the planet by creating or enhancing life-sustaining conditions. One such contradiction is maintaining economic growth while protecting the environment. As data and history show, these two objectives sit at opposite ends of the development matrix.

Economic growth always results in increase in consumption, which in turn fuels production. Increased production leads to additional consumption of raw material and energy. This is a self-feeding cycle that has kept expanding throughout the industrial age. Therefore, to place them in the same basket ofSDGs is untenable. Science too points towards this inherent flaw in the SDG framework. “Many studies concur that the SDGs lack ambition and coherence to foster a transformative and focused push towards ecological integrity at the planetary scale,” note the authors of the paper.

The reason for this lackadaisical approach is easy to understand. “There are indications that this lack of ambition and coherence results partially from the design of the SDGs, for example, global economic growth as envisaged in SDG 8 (notwithstanding regional development needs) might be incompatible with some environmental protection targets under SDGs 6, 13, 14 and 15.”

The scientists note that national priorities often result in putting the various goals at odds with oneanother. “Experiences from the implementation of the SDGs in domestic, regional and international contexts provide little evidence of political impact towards advancing ecological integrity, as countries in both the Global South and the Global North largely prioritize the more socioeconomic SDGs over the environmentally oriented ones, which is in alignment with their long-standing national development policies.”

Increased production leads to additional consumption. This is a self-feeding cycle that has kept expanding throughout the industrial age

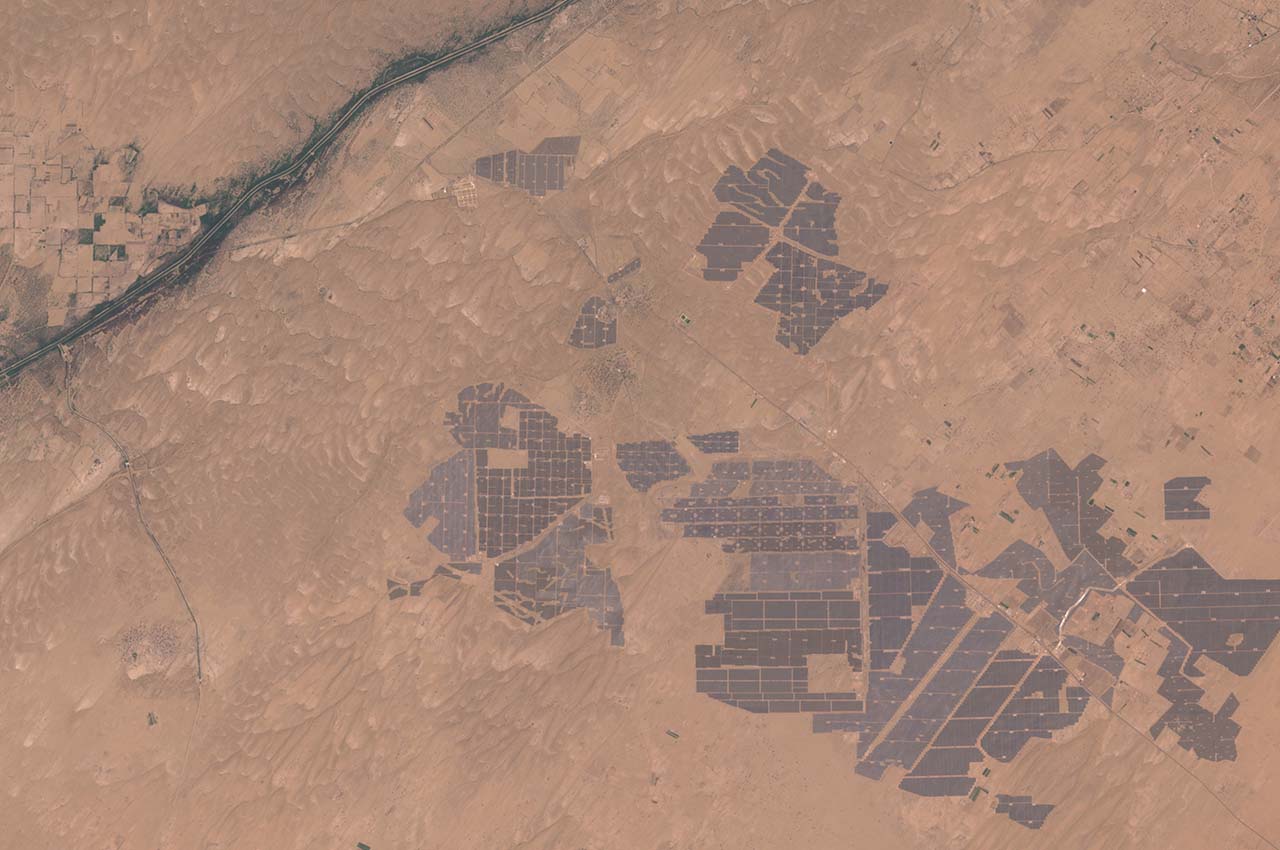

A typical example of this inherent contradiction between economic development and ecological integrity built into the SDGs was highlighted in the March issue of Tatsat Chronicle. India has embarked on an ambitious project of producing 500 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy as part of its energy transition strategy toward fulfilling the obligations under SDG 7.2. The article detailed how, in the race to increase generation of the green power to meet the target of 500 GW by the end of the decade, setting up mega solar power generation parks have become the order of the day. The case of the Solar Park spread over 14,000 acres in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan is a textbook example of conflicting SDGs.

According to the publicly available information, this mega solar power generation complex has been developed on what has been officially classified as wasteland in the land records. In other words, this piece of real estate has no practical use. But a perusal of long-term district land records revealed that the so-called “wasteland” was used by the local people as pasture for their cattle and livestock, besides being the natural habitat for a variety of wildlife such as chinkara, blackbuck,jackals and jungle cats, to name a few. The case study highlighted the clash between SDGs 7.2 and 15, which states: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. There is no doubt that the Bhadala Solar Park has resulted in biodiversity loss.

Since the SDG framework is a set of guidelines, without any legally binding mechanism, this leaves them open to interpretations according to the convenience of nations, say the authors of the paper. “The SDGs are a non-legally binding and loose script, purposefully designed to provide much leeway for actors to interpret the goals differently and often according to their interests. Hence, many actors seem to use the SDGs for their own purposes by interpreting them in specific ways or by implementing them selectively.”

The interim UN report underlines the speed-breakers that are hampering energy transition that has been accorded priority in European countries

The interim UN report too underlines the speed-breakers that are hampering energy transition that has been accorded priority in almost all European countries and in some in Asia, including India. “The impacts of climate change are already being felt across the world and COVID-19 further delayed the urgently needed transition to greener economies. While the economic slowdown and COVID-19 lockdowns led to the temporary reduction of CO2 emissions in 2020, global energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 6.0% as demand for coal, oil and gas rebounded with the economy in 2021. Based on current national commitments, global emissions are set to increase by almost 14% over the current decade, which could lead to a climate catastrophe unless governments, the private sector and civil society work together to take immediate action.”

In India’s case, fulfilling Agenda 2030 is looking increasingly remote. According to the State of India’s Environment Report 2022, released by the Centre for Science and Environment in March this year, India’s ranking dropped from 117 last year to 120 this year on the 17 SDG indicators, slipping behind Bhutan, Nepal and Bangladesh. India’s overall SDG score was a mere 66 points out of a total of 100. Poor scores on some of the key parameters such as zero hunger, good health, elimination of poverty, gender equality, well-being, education for all and sustainable cities and communities, dragged down India’s ranking.

Given the volume of evidence that is piling up with each passing year about the failure of the SDGs to make a meaningful normative and transformative impact, it’s clear that the framework suffers from serious design flaws. At the same time, given that it’s not backed by any legal mechanism, countries like India, and other developing nations, are bending it for their convenience, which in realistic terms won’t bring substantiative change.