The world is threatened by global warming and India, as expected, is attempting to play a leading role. In the short foreseeable term, it aims to meet half of its energy requirements from renewable sources and reduce carbon emissions by one billion tonnes by 2030. India hopes this will put it firmly on the path to achieving the relatively long-term goal of zero net emissions by 2070. The objectives that India has set are laudable, particularly since they tie in well with commitments under the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and its climate change targets. Serious doubts, however, begin to creep in as soon as details of the roadmap are subjected to closer examination.

It makes more sense to consider the 2030 targets first since they are likely to fall within the lifetime of the present generation. Like many other countries, India has chosen to concentrate its focus on reducing carbon emissions from the power sector because it is the sector easiest to control and manage. Besides, electricity generation is the single most important source of emissions, accounting for around 40% of the global energy-related CO₂ emissions. Though SDG 7 covers the overall goals of the energy sector, it is 7.2 that specifically deals with renewable energy. The other sections of SDG 7 are concerned with clean cooking fuels and improving energy efficiency, but they are more difficult to achieve.

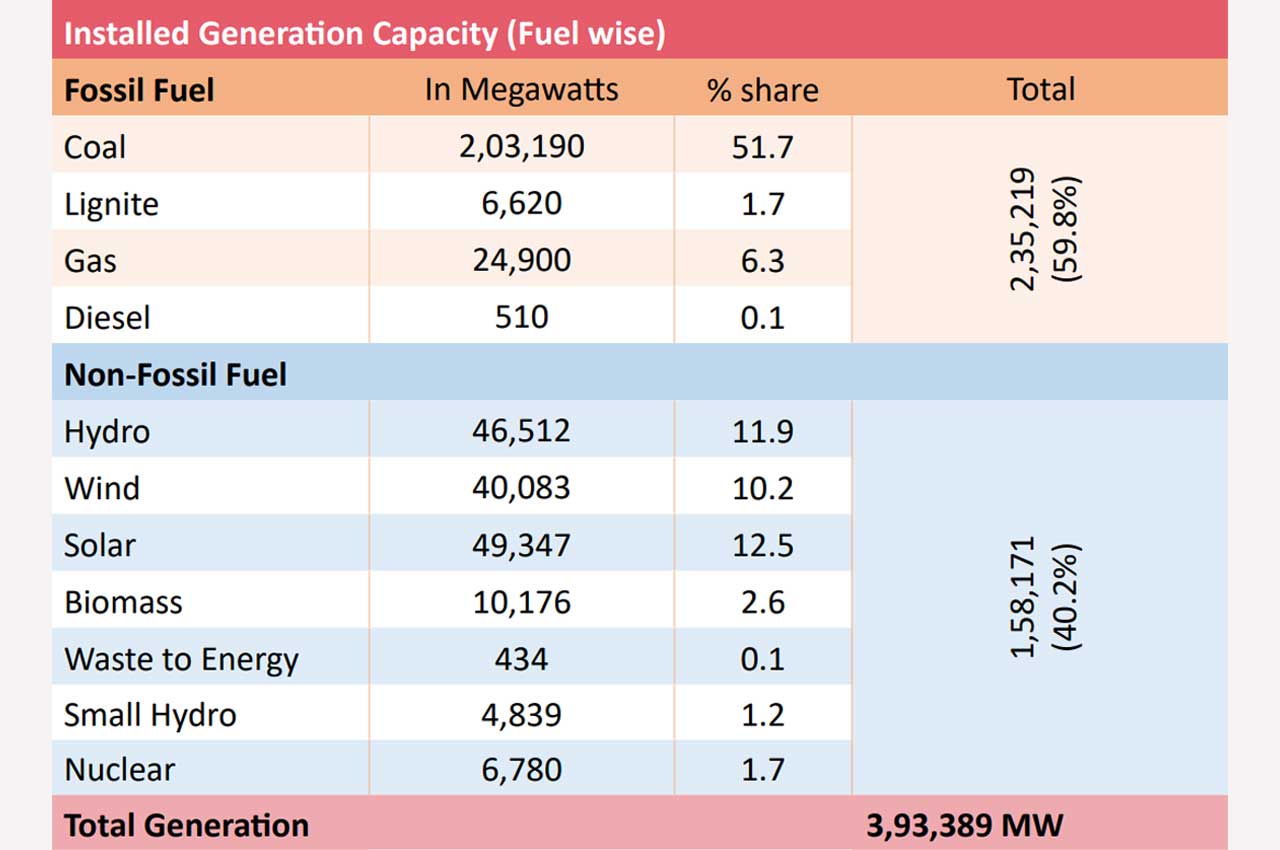

To focus, therefore, on the power sector, as per the latest figures, the total installed capacity from all sources is 393 gigawatts (GW). Assuming that this figure would have approximately doubled by 2030, given current levels of growth in demand, it would mean that the capacity of renewable energy would have to increase to 50% or around 400 GW. Therefore, the targeted renewable capacity of 450 to 500 GW seems to be just right.

It makes more sense to consider the 2030 targets first, since they are likely to fall within the lifetime of the present generation. Like many other countries, India has chosen to concentrate its focus on reducing carbon emissions from the power sector because it is the sector easiest to control and manage

The obvious way of weaning the country away from fossil fuels, essentially coal and petroleum-based fuels, is to meet energy needs stemming from economic growth by the rapid increase in green sources of energy — mainly solar and wind power. And the problems lie at this juncture.

To start with, considering the rate at which the creation of renewable energy capacity has been progressing, is 2030 a realistic date for achieving a capacity in this sector running to between 450 to 500 GW? Perhaps it will help to break up the components of the renewable energy sector to remove confusion

They are essentially two-fold. The first is whether it is realistic to assume that the target of 500 GW non-fossil fuel energy can be achieved by 2030 — a deadline which is barely eight years away, particularly in view of the fact that to date just a fifth of the ambitious target has been reached. The second is more serious and is concerned with the uncertain long-term environmental impact of the large up-scaling of renewable energy capacity, to which little thought appears to have been given.

It stems from the government’s plans to utilise what is officially described as “wastelands” to set up mega solar power parks covering thousands of acres. But what under the official gaze are classified as “wastelands” are in fact made up of grasslands and wetlands, which support complex ecosystems. The big question that arises therefore is whether the remedy itself is worse than the disease since it could result in the destruction of the very environment it professes to be saved. This is likely to run counter to SDG 15 which aims, among other things, to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems”. While setting out the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015, the UN made it clear that the 17 goals, including the three relating to the environment (13, 14 and 15) have to go hand-in-hand and cannot be pursued in exclusive silos.

To start with, considering the rate at which the creation of renewable energy capacity has been progressing, is 2030 a realistic date for achieving a capacity in this sector running to between 450 to 500 GW? Perhaps it will help to break up the components of the renewable energy sector to remove confusion. But first a look at the meanings of the terms green energy, non-fossil energy and renewable energy. For the uninitiated, the term ‘non-fossil sources’ is not to be confused with solar and wind alone. Non-fossil energy sources include, in addition, small hydropower, biomass power, waste to energy, and even nuclear power. Strictly speaking, the term ‘clean energy’ can be applied only to two categories — solar and wind — since the harmful effects of nuclear and hydropower are well known. And even biomass and waste-to-energy are carbon emitters. But often the term ‘non-fossil’ is used alongside ‘clean energy and solar and wind power though there are important distinctions between them.

An 11-fold increase in solar power capacity between 2014 and 2019 may look good. But scrutiny of absolute numbers shows that the picture may not be that rosy. The increase has been from 2.6 GW (2014) to 28 GW over five years — total growth of a little over 25 GW in five years. By August 2021, the total installed capacity of solar plus wind power had reached 85 GW of which the share of solar was 46 GW. So, despite the addition of 18 GW within two years, the target of 100 GW of installed solar power capacity appears to be well beyond reach.

In 2016 the government found a way out of the problem by developing at least 25 mega solar power parks of minimum 500 MW capacity each. Initially, the target was to create an additional capacity of 20 GW but this was raised within a year to 40 GW and the deadline was extended by two years to 2021-22.

The biggest of the parks, described as ‘ultra-mega solar power projects’, are located in Rajasthan and Karnataka. It would be useful to take a look at the profiles of these parks to get an idea of the size of the projects in terms of area covered and the problems they would pose for the implementation of SDG 15.

The world’s biggest solar park has come up in Bhadla village in the Jodhpur district. Commissioned in March 2020, it is spread over 14,000 acres (45 sq km) and has a capacity of 2,245 MW (2.2 GW). It is said that the park takes full advantage of a “dry and barren wasteland” to produce solar power from the abundance of sunlight available in Rajasthan. But that is only part of the story. What has been left unsaid is that the dry and barren wasteland may be somewhat dry, but is definitely not barren — supporting as it does a complex ecosystem.

It would be surprising to reveal the quantity of flora and fauna that live in what is carelessly described as ‘dry and barren wasteland’, as in the case of the Bhadla Solar Park. According to the district environment plan of Jodhpur, about a twentieth of the total area of the district of 22.5 lakh hectares consists of permanent pastures and grazing lands (1.22 lakh hectares). A little under 16 lakh hectares are under cultivation. The balance, therefore, is roughly five lakh hectares which include non-agricultural (urban) and fallow land (not necessarily waste) and forest land.

But a ‘Degraded and Wasteland’ survey jointly conducted and published in 2010 by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and National Academy of Agricultural Sciences has declared as much as 12 lakh hectares of land in Jodhpur district (more than 50%) to be a wasteland. There is no other explanation for this discrepancy unless permanent pastures and grazing lands have also been included in the category of wasteland. Recent news reports confirm that the pastoralists of Bhadla have indeed been driven out of their occupation and have sold their cattle as there are no pastures left after the establishment of the solar park.

It would be instructive to take a look at the flora and fauna supported by these wastelands. The Bhadla district environment plan says that the animals found there include the jackal, jungle cat, Indian fox, blackbuck, chinkara, and the common hare, to name a few. Birds include the baya, koyal, vulture, jungle crow, bulbul, kite, sand grouse, common quail, grey partridge, and little egret. A special tourist attraction is the GudaVishnoyian Conservation Reserve maintained by the Bishnoi community that believes in the sanctity of animal and plant life. Chinkara, blackbuck, and wild boar thrive in this preserve dotted with Khejri trees and even a lake which attracts migratory birds. Obviously, to use the nomenclature of wasteland to describe such land is grossly misleading.

According to Dr Abi Tamim Vanak, an ecologist and associate professor at the Bengaluru-based Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE), open natural ecosystems like grasslands have been “historically undervalued in India even though they are highly biodiverse and critical ecosystems. Currently, India gives a free pass to promoters of solar and wind energy in terms of environmental regulation. This needs to change. Both solar and wind can have tremendous impacts because of their enormous land footprints”.

Dr Vanak says that most utility-scale solar farms are situated in semi-arid savannah grasslands of India. And solar panels can create “dead zones” particularly if they are mounted close to the ground. Solar farms, he adds, are usually fenced, excluding both wild animals and pastoralists from thousands of acres of habitat.

According to Dr Jayashree Ratnam of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, the savannahs of Asia remain “locally unrecognised” as distinctive ecosystems and continue to be viewed as degraded forests or tropical dry forests. This, she says, is a continuation of the colonial-era legacies that fail to recognise the unique diversity of Asian savannahs and the critical roles of fire and herbivory in maintaining ecosystem health and diversity. In the colonial era, the approach was forest-centric as foresters were trained in the European tradition and tasked with describing Asian vegetation mainly from the point of view of timber and other extractive uses. What was ignored in this view of the savannahs as degraded forests was that they have been used and managed by humans for thousands of years.

That large tracts of land in Rajasthan have been classified as wastelands and therefore could be used for the “useful” activity of renewable energy generation to check global warming seems to be a left-over of the colonial mindset. The lands in Bhadla that have been covered by the solar park are a prime example of the Asian savannah being classified as wasteland and being taken over for a nobler cause of stepping towards fossil fuel-free power generation. SDG 15 can take a back seat.