Last year, Indian Railways invited applications for 35,000 posts it had created for non-skilled workers called Non-Technical Popular Categories. A total of 12.5 million (1.25 crore) candidates, mostly youth, applied. They included some holding master’s degrees and PhDs when the requirement was Class 12 pass for undergraduate posts and graduation for graduate posts. Almost 360 persons applied for each post which was not even high-paying.

This January, when the first shortlist was declared, most of those who did not make it blamed the Railway Recruitment Board (RRB) for messing up the exams. The anger soon led to violence, with thousands blocking railway traffic in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh — the states to which the maximum number of applicants belonged. At least one empty train was torched. When the RRB offered to set up a committee to examine the issues involved, some of the anger subsided, but the incident underlined the tinder-box unemployment scenario across the country.

The youth feels betrayed by a government that came to power in 2014, and again in 2019, promising to expand job opportunities by the millions. Not only did the promise to create 20 million jobs fail to materialise, but unemployment has also risen, exacerbated by several retrograde government policies and a raging coronavirus that laid waste the hopes of millions. The joblessness is fast giving way to hopelessness.

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the unemployment situation worsened in December 2021 to 8% from 7% the month before. A total of 53 million people are looking for jobs in a country of 1.35 billion where only a little over 400 million people are employed. This does not include many more frustrated millions who do not care to look for employment because none is available.

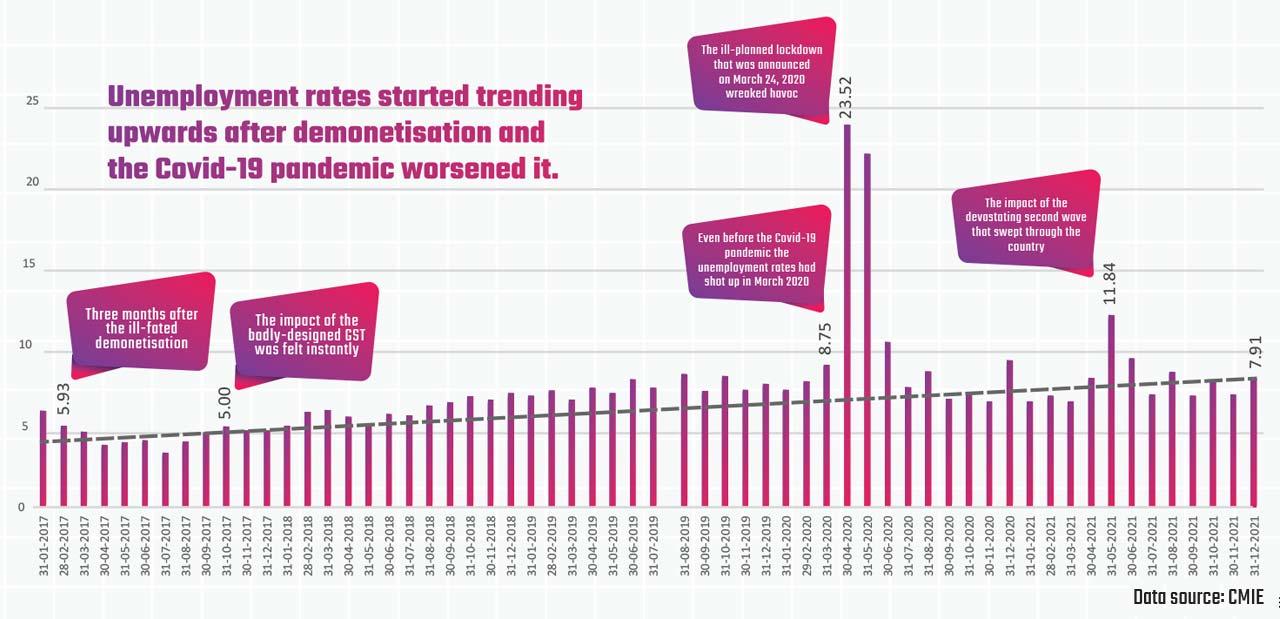

India’s unemployment rate was not too encouraging at 5.6% in 2014 when the Narendra Modi government came to power. Before the Covid-19 pandemic caused widespread devastation, the rate was already in the ascendancy. This January, it had gone over the 8% mark. By 2018-19, the labour force participation rate increased only marginally to 50.2% from 49.8% the previous year. In 2011-12, it was 55.9%, according to the survey by the National Statistics Office.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey of the government, set up to provide better statistics, submitted a report for 2017-18 which was suppressed by the Centre despite two high-level officials resigning in protest against the government’s refusal to make the report public. After completion of the 2019 general election, the government released the report which showed that the unemployment rate for 2017-18 was the worst in 45 years. The labour force participation touched a low of 36.9%, according to the report, but the central government rejected the findings of one of its own statistical arms, saying the figures were not comparable with the old numbers.

Demonetisation and GST

On November 8, 2016, at 8 pm, Prime Minister Modi announced a government decision that would have consequences far and wide, reverberating over subsequent years in the economy, the job market and citizen trust in the government. The government demonetised or rendered illegal the ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes, thus undercutting the trust of citizens in the fiat currency.

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the unemployment situation worsened in December 2021 to 8% from 7% the month before. A total of 53 million people are looking for jobs in a country of 1.35 billion where only a little over 400 million people are employed. This does not include the frustrated millions who do not care to look for employment

The government’s three avowed objectives were to fight black money, remove corruption, and cut down terror funding. The government estimated that around ₹3 lakh crore of the total 15.4 lakh crore high denomination currency notes would not come back into the system, thus eliminating much of the black money. However, 99.3% of the total high denomination currency in circulation (86.4% of the total currency in circulation) came back into the banking system, in exchange for the new notes. Only about ₹10,720 crore did not come back into the system. But the government brushed this aside without any discussion or explanation. The impact on corruption or terror funding remains unknown. In December 2021, the total currency in circulation shot up to ₹29.84 lakh crore, which is almost double the pre-demonetisation level.

Additionally, according to CMIE estimates, about 1.5 million people lost their jobs. An estimated 1.5% of the GDP or ₹2.25 lakh crore vanished and, according to the former finance minister, P. Chidambaram, about 15 crore daily wage earners lost their livelihoods. Besides, over 100 people lost their lives, linked directly to demonetisation.

The job loss estimate will always remain a guess because a vast percentage of the Indian economy in the informal sector depended on the cash economy. Overnight, a tsunami ripped through this sector, rendering millions without the means to carry out their work or informal business. The real price paid for a largely misconceived policy of the government can never be measured.

The government’s three avowed objectives were to fight black money, remove corruption, and cut down terror funding. The government estimated that around ₹3 lakh crore of the total 15.4 lakh crore high denomination currency notes would not come back into the system, thus eliminating much of the black money. However, 99.3% of the total high denomination currency in circulation came back into the banking system

In July 2017, the government brought in a far-reaching policy of consolidating many taxes into one Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India. The hasty introduction meant that over the next several months the tax rates kept getting tweaked; the online system that had dozens of glitches kept being reworked, and the government kept changing its approach from week to week. The result was a disproportionate impact on small and medium companies, resulting in closure of thousands of businesses.

The CMIE said that 2017-18 was difficult because of the effects of demonetisation and GST, which also reflected in the high unemployment rate. “So ideally, 2018-19 should have shown an improvement, but it has not changed significantly,” officials of CMIE said.

Writing in the New York Times, Kaushik Basu, professor of economics at Cornell University and former World Bank chief economist, said that demonetisation proved to be a “terribly misguided” policy, and the introduction of GST was “a move in the right direction but poorly executed”.

The twin disastrous policies of demonetisation and the hasty introduction of GST will leave their mark for many years to come. The policies have severely impacted the informal sector in the country, and the small and medium enterprises, which together provide jobs to about 90% of the gainfully employed, have been left severely bruised.

Basu, who also served as the chief economic advisor to the Government of India from 2009 to 2012, said in a recent interview to Business Today TV that the economic policy framework followed by Modi has worked well for the top-end of India, which is doing well but has misfired for the bottom segment, which is worse off than before. “From 2016, India’s growth every year is lower than the previous year. For the past five years, each following year is doing worse…this has not happened since 1947, creating a pretty grim situation for workers, farmers and even for the middle class,” said the renowned economist.

Job-killing virus

Even though the job scenario remained sluggish till the end-2019, the next year saw an event for which the world was not prepared, although scientists had predicted for years that a pandemic was likely to hit. From January 2020, things moved pretty fast, enveloping an unwary nation in challenges it had never faced.

A government’s response can either ameliorate or worsen a situation. In March 2020, when the government announced the first nationwide lockdown, it seemed to not have thought through its decision or prepared itself to face the consequences of its action. Lockdown meant that most people had to prepare to stay at home and let the tide brought by the virus wash over.

But what about the migrant workers? The daily wagers? The odd-job workers? These were not a minuscule number. They amounted to several millions all over the country. For the next several days, the migrant workers from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and other states made their way — on foot, on bicycles, on motorcycles — towards their homes. Unable to sustain themselves and their families without a job or help, they preferred to go home. There was no response from the government when these millions trudged hundreds of miles on the country’s roads with family members, several of them dying on the way. Suddenly, the dimension of the problem was visible on news screens across the nation, every day. Yet the government kept quiet. The response came from private individuals and organisations, whose move to help with food and transport had a limited impact, though.

On the unemployment front, worse — much worse — was to follow. The monthly unemployment rate went up to 23.5% in April 2020 and 21.7% the next month, according to the CMIE data. The number of people with jobs saw a drastic decline from 407 million in 2016-17 to 378 million in 2020-21. Except for agriculture and non-financial services, the industrial sectors saw employment decline between 2016-17 and 2020-21. Instead of pulling out workers from farms into factories — as has been the trend over decades all over the world — India witnessed a sharp drop in factory employment and a slight increase in farmworkers. Was this a retrograde step or a desperate response by those who could not find any work in urban settings?

There was no response from the government when millions trudged hundreds of miles on the country’s roads with family members, several of them dying on the way. Suddenly, the dimension of the problem was visible on news screens, every day. Response came from private individuals and organisations, whose move to help with food and transport had a limited impact, though

The joblessness did not impact the sexes equally. Women were the worst sufferers. According to the Economic Survey, while 9.52 million women actively searched for work every month in 2019, that number declined to 8.32 million the next year and 6.52 million in 2021. Many millions gave up searching and reconciled themselves to not finding any job. This hopelessness is writ across the nation’s brow. Innumerable young persons are withdrawing from the job market. No wonder the frustration of the youth seeking jobs, as in the Railways recruitment fiasco, turns into a violent protest.

The growing hopelessness

The latest budget professes to create six million jobs over the next five years. But looking at the promises made by this government, time and again, on job creation, the chance of that materialising seems low. The Modi government came to power in 2014 on a plank of development along with job expansion. But it soon meandered into self-defeating policies such as Atmanirbharta (self-reliance), which generally results in an insular polity. The Made-in-India mantra resulted in protectionism making it’s way back into the system.

The Congress pursued the policy of self-reliance for decades, only to jettison it, with its back to the wall, in 1990 when the nation was on the verge of becoming a basket case. That Modi would re-adopt such a policy is ironic. The Swachh Bharat Mission, Smart City Mission, Start-Up India were merely tinkering with the system, not steps towards bold reforms. The annual growth rate of per capita net national income went down from 6.29% in 2016-17 to 2.5% in 2019-20 and to –8.4% in 2020-21 (due to the Covid-19 pandemic) with recovery in 2021-22 to above 8% likely, according to the latest Economic Survey. Given that the projected growth would be on a low base, this would mean the economy won’t be expanding significantly. At best, it will reach the pre-pandemic level.

After 1990, liberalising policies resulted in around 1.4% of the population moving into the middle class until 2015-16. But millions were pushed into poverty in the years that followed. According to a report by Oxfam, over 46 million Indians fell into poverty in 2020, while the number and wealth of billionaires surged. The figures may be debatable, but many economists agree that rural wages declined in the past five years. The rising demand for jobs under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee programme underlines the job distress in rural India. According to CMIE data, unemployment woes have dogged the nation since 2016. In January of that year, the unemployment rate was 8.7%, sharply increasing to 23.5% during the first wave of the pandemic in April 2020 only to recover to a still serious level of 8% in December 2021. Unemployment has been even worse in the younger age group. During October-December 2021, the unemployment rate was 41.31% in the 20-24 age group. If this does not sound alarm bells, very little will.

Manufacturing, the backbone of the employment structure, has been neglected by the Modi government while paying only lip service to this sector. According to the latest Economic Survey, the share of manufacturing in employment dropped from 5.65% of new workers added in 2018-19 to 2.41% in 2019-20. The CMIE says that over 50 million people were employed in manufacturing in 2016-17, which dropped sharply to 27.3 million in 2021. Similar snapshots of decline were seen in construction and mining, which generally boost employment. In the end, the joblessness situation turning hopeless for many can be laid at the door of the government. A failure of governance combined with severely debilitating policies like demonetisation, ignoring the plight of migrant workers during the pandemic, a cranked-up atavistic Hindutva movement against minorities and a government making piecemeal changes while ignoring bolder policy reform would obviously result in millions going without a job while millions more would just stop looking for employment. If this government doesn’t respond to the job crisis knocking on its doors, its raison d’etre will come under a big question mark.