Will the central government give effect to the four labour codes by notifying the rules, now that the ruling BJP has been endorsed by voters in four out of five states in the recent elections? Hope among employers of this happening had dimmed after the central government decided to withdraw in November 2021 the three farm laws it had enacted in September 2020 on agricultural marketing, stockholding and contract farming, following a 378-day protest by farmers who established a siege on Delhi’s borders. With the BJP winning a decisive mandate, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and even in the eight assembly constituencies in Kheri—where farmers protesting against the farm laws were mowed to death—it is unlikely to be on the back foot.

The Lok Sabha had passed the Code on Wages in July 2019. The Rajya Sabha gave its approval the following month. Bills pertaining to three other codes on occupational safety, health and working conditions, industrial relations, and social security were passed in September 2020. These codes meet the long-voiced demand of employers. They replace 29 pieces of central legislation and make life easier for employers with fewer compliances. There is provision for inspections, especially those related to safety like those of boilers by third parties approved by the government. Approvals are deemed given if a decision, adverse or otherwise, is not communicated within a stipulated time. There is a provision for compounding some offences with a fine in place of a jail term.

Radical changes

The first drafts of these codes were published for public comments in 2014. There were several rounds of consultations with industry, trade unions, and government representatives thereafter. Two committees of Parliament examined them. Despite the consultations, there was push-back from some state governments and the trade unions, including the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, affiliated to the ruling party. But consultation does not mean consensus, says Pradeep Bhargava, co-chair of the Confederation of Indian Industry’s (CII) Committee on Industrial Relations. He expects the rules to be notified and the codes to be operationalised in this calendar.

Approvals are deemed given if a decision, adverse or otherwise, is not communicated. There is provision for compounding of some offences with a fine

Since labour is a concurrent subject with the Centre having the authority to enact legislation for employees in industries under its domain, like banking, railways, mines and oilfields, and the states having authority regarding others, the laws have to be separately enacted by the states and the rules notified by each of them for the codes to take effect in their domains. According to Bhargava, out of the 36 states and Union Territories, 23 have issued draft rules on wages, 20 on occupational safety, 19 on social security, and 15 on industrial relations. Fifteen states and Union Territories have published the rules for all four codes.

Among the key highlights are fixed-term contracts under which employees enjoy all the rights and benefits of permanent workers. This will help industries where demand varies with fashion like those engaged in garment exports, or those executing projects. In the absence of this flexibility, employers were said to hesitate to take workers on their rolls for fear of not being able to lay them off, when not needed. Bhargava says fixed-term contracts will aid the formalisation of the workforce. Employers will have an incentive to invest in upgrading their skills. This should improve the general skill level, nationally. In the absence of fixed-term contracts, employers would take people on contract for, say, 90 days, after which they would be re-employed with a break in service. Contract workers have truncated rights and benefits. The difference between them and permanent workers is stark.

Fixed-term contracts are “good”, says Santosh Mehrotra who was director-general of the National Institute of Labour Economics Research in the erstwhile Planning Commission from 2009 to 2014. But the contracts will have to be of at least two to three years for them not to be exploitative, he says.

The Parliamentary committees had wanted the conditions and areas of fixed-term employment to be specified. They also wanted the law to state the minimum and maximum tenures. These recommendations were not accepted.

The code on industrial relations has exempted establishments employing less than 300 workers from seeking government permissions in case they need to lay off workers. Under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (IDA) the limit was 100 workers. But governments would invariably deny permission for dismissal owing to pressure from trade unions, and to avoid being perceived as anti-labour.

Removing regulatory cholesterol

In a chapter on the structural changes that the Indian labour market needed to create ‘good jobs’, the 2015-16 Economic Survey identified ‘regulatory cholesterol’ or the difficulty of dismissing workers under IDA as a principal reason that came in the way. As a result, the formal sector was adding very few safe and well-paying jobs. Of the 10.5 million manufacturing jobs created between 1989 and 2010, the Survey said only 3.7 million or about 35% were formal. And of the 4.2 million establishments added during this period, the formal sector accounted for just 1.2%. But there was a change in trend from 2000 onwards. The informal establishment count flattened, and employment actually fell, while formal employment picked up.

The Parliamentary committees wanted the conditions and areas of fixed-term employment specified. They also wanted the law to state the minimum and maximum tenures

The Survey attributed this to increased resort to contract labour, which had risen from 12% of all registered manufacturing workers in 1999 to 25% in 2010. The trend was striking in establishments employing more than 100 workers, which needed permission to lay off. Though large firms increasingly resorted to employing workers on contract to meet their additional requirements, they did not prefer this mode. Hiring workers through contractors was 14% more expensive, the Survey said, quoting the Indian Cellular Association. Contract workers did not feel loyalty to the firm. It also affected a firm’s future productivity as contract workers did not accumulate “firm-specific human capital”.

Bhargava expects labour-intensive industries like garment-making to shift to India once the code on industrial relations takes effect. These industries had relocated from China, owing to high wages there, to Bangladesh and Vietnam. The Survey said India’s apparel sector was dominated by small firms. About two million establishments employed 3.3 million workers or an average of 1.5 workers, while the formal sector’s 2,800 establishments employed 3.3 lakh workers or 118 each on average. Formal sector apparel firms were 15 times more productive. With relatively low wages, India should have been among the big apparel exporters as wages account for about 30% of the cost, while capital-intensive inputs like power account for 2-3% of the cost.

Mehrotra says unions were not averse to giving flexibility to employers to adjust their employment count as per business demand. They could have been brought around by hiking the compensation payable to laid-off workers from two weeks’ pay for every year of service to six weeks’ pay. This was reasonable as India does not have unemployment benefit and displaced workers (and their families) should have a safety net.

Social security imperative

The social security code brings gig and platform workers within its ambit. It mentions nine categories of aggregators, including taxi hailing, food and grocery delivery, content and media services and e-marketplaces. It provides for their registration and for a board comprising 16 members, including five members of aggregators nominated by the central government, five members of platform and gig worker unions, the head of the Employees’ State Insurance Corporation and five representatives of state governments. It will administer a fund made up of contributions from the central government, state governments and aggregators. The aggregators’ contribution is to be 1-2% of annual turnover, but not more than 5% of their annual payment to gig and platform workers. The law expands the definition of employees to include workers employed through contractors.

Inter-state migrant workers earning less than ₹18,000 a month are entitled to certain benefits like the option to avail of rationed grain either in their home state or the state of employment

Inter-state migrant workers earning less than ₹18,000 a month are entitled to certain benefits like the option to avail of rationed grain either in their home state or the state of employment. States have to maintain a database of migrant workers. The migrant workers can also self-register on the e-Shram portal. As of mid-March, 1.27 million migrant workers were registered. They are entitled to benefits from a fund created out of building and construction cess.

The industrial relations code requires 14 days’ notice for a strike or lockout, which must also be given to the conciliation officer, who will begin proceedings immediately to avert it. If conciliation fails, the dispute will go to an industrial tribunal, whose award must be enforced within 30 days, though the states and the Centre can reject it. Strikes and lockouts are prohibited during and up to seven days after conciliation proceedings and during and up to 60 days after proceedings before a tribunal. Parliament’s standing committee wanted the restriction on strikes to apply only to public utility services and not all establishments. Bhargava says strikes and lockouts are not bilateral matters between employers and workers; in these days of just-in-time inventory, they disrupt the entire supply chain. He thinks the restrictions are fair.

The new law recognises trade unions with at least 51% membership as the sole negotiating union. If there is no such union, there is provision for a negotiating council

The new law recognises trade unions with at least 51% membership as the sole negotiating union. If there is no such union, there is provision for a negotiating council comprising unions with at least 20% membership. But what if membership is fragmented and there are many unions in an establishment with less than 20% membership?

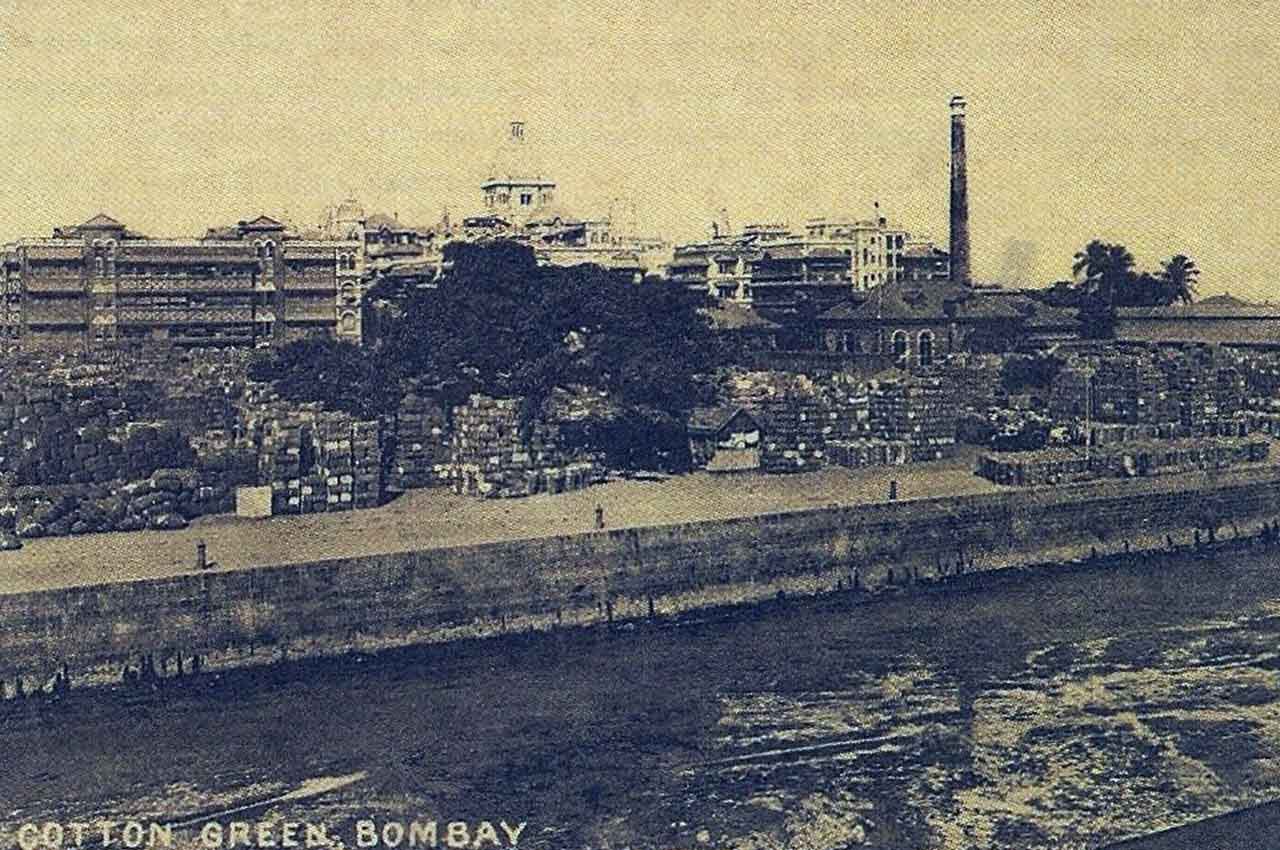

Of course, the power of trade unions has vastly diminished since 1982-83 when about 2.5 lakh textile mill workers in Mumbai struck work for 18 months. According to Maharashtra’s 2021-22 Economic Survey, there were 636 strikes and lockouts in 1981, affecting a little over two lakh workers, resulting in a loss of work of over 95 lakh person-days. In 2020, there were just 64 incidents, involving 6,400 workers and a loss of 16 lakh person-days of work. As a leading industrial state, Maharashtra mirrors the trend.

Not so incidentally, the code on occupational safety, health and working conditions allows state governments to exempt any new factory from its purview to create employment and stimulate economic activity. But should economic and employment growth happen at the cost of workers’ safety? Though establishments using power and employing less than 20 workers are exempt from it, it covers all those engaged in a hazardous activity. Contractors too come within the ambit if they employed 50 or more workers per day on any day in the past year. Contract labour is prohibited in core activities. Non-core activities are listed. There are 11 of them where the prohibition on employing contract workers will not apply: sanitation workers, security services and any activity of an intermittent nature even if it is the core activity of an establishment.

According to Maharashtra’s 2021-22 Economic Survey, there were 636 strikes and lockouts in 1981, affecting a little over two lakh workers, resulting in work loss of over 95 lakh person days

Going by the hope that employers like Bhargava have invested in them, the codes are a step to change. But Mehrotraw says they are “largely a scissors and paste job”. The codes certainly have novel elements in them, but their effectiveness will depend on enforcement in which India has lagged so far. India certainly needs laws that enable the creation of safe and well-paying jobs. But for that, the economy must grow. This is a function not only of enabling laws but also of social harmony.