Farmers are protesting again. Just a little over two years after they withdrew their year-long siege on Delhi’s borders following the withdrawal of the three farm laws and assurance provided by Prime Minister Narendra Modi through a nationwide, prime-time television address of redressal of their issues, they have revved up their tractors—this time to hold the government to account for failing to fulfil the promises made in November 2021.

Even before Farmer Protest 2.0 started to gather momentum, India’s cultivators have been agitating, albeit on a smaller scale, in the villages, blocks, and towns of rural India. But the issue has remained the same — providing them remunerative prices for their produce.

Since Independence, farmers in different parts of the country have risen up in protest to demand their rights at different points in time. In the late 1940s, sharecroppers in Bengal launched the tebhaga movement, demanding two-thirds of the produce. Spurred by the Left political parties, the agitation spread across villages. It was, perhaps, the most intense peasant revolution in India. The movement culminated in 1950 with the introduction of the Bengal Bargadars Temporary Regulation Bill, 1950.

But it was not until the Mahendra Singh Tikait-led agitation in 1988 which brought Delhi and the Rajiv Gandhi government to a grinding halt that a farmer agitation occupied centre stage. The sheer optics of lakhs of agitating farmers occupying the lawns of the Boat Club and Vijay Chowk in the heart of the capital made India’s cultivators a political force to reckon with. Tikait catapulted to fame in 1987 following a campaign in Muzaffarnagar demanding waiver of electricity bills for farmers. The next year, Tikait sprang a surprise by holding a well-attended dharna outside the office of the Commissioner at Meerut—then divisional headquarters—demanding a hike in sugarcane prices.

Some three decades later, it was his son, Rakesh, who managed to keep the sit-in demonstration at Delhi’s borders going when thousands of protesters began the long trek home after a tractor march went awry on Republic Day in 2021. They turned their vehicles around after a clip of a sobbing Rakesh Tikait rending an emotional speech went viral. The siege on Delhi’s eastern and northern borders by multiple farmer bodies lasted until the government of the day repealed the three farm laws.

Why are farmers agitating?

Just like the last time, people are wondering why farmers are agitating. Why this recurring show of strength? The general perception among people is that Modi has introduced a slew of measures to improve the lot of farmers. The Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) of ₹6,000 per annum to cultivators has been cited by supporters of the government as an example of it being pro-farmer. Some point to the formation of the Inter-Ministerial Committee (IMC) in 2016 for doubling of farmers’ income (DFI) as a weathervane of the government’s good intentions. As it turned out, the 3,000-page, 14-volume report prepared by the IMC leaned heavily towards “corporatisation” of agriculture, though it recommended continuation of Minimum Support Price (MSP) along with other market reforms.

But, except for the corporatisation part, which found its way into the repealed farm laws, all other suggestions were ignored. Instead, under instructions from the government, NITI Aayog set up a task force headed by a software entrepreneur and stacked it with representatives of the corporate sector without including a single member representing the farmer bodies. The recommendation of this task force resulted in the three contentious farm laws, which forced the agriculturists to hit the streets and lay siege to the capital. Ultimately, with an eye on the approaching UP Assembly elections in February 22—a key state in the BJP’s political calculus—Modi announced withdrawal of the three farm laws in November 2021 and promised to enact a law that would codify MSP.

Rhetoric and numbers don’t add up

While the government misses no opportunity to wax eloquent about its intent of increasing the income of farmers, its actions, reflected in the Budget, tell exactly the opposite story. The Budget Estimates (BE) for 2023-24 for the agriculture ministry was ₹1.25 lakh crore. Food subsidy in the BE has been pegged at ₹1.97 lakh crore, which is 31.2% less than the revised estimate (RE) of 2022-23. Meanwhile, fertiliser subsidy has been estimated at ₹1.75 lakh crore, which is again 22.2% less than the RE of 2022-23. Similarly, the BE for several of the Centre’s flagship schemes for agriculture were less than the RE of the previous year (see Table 1).

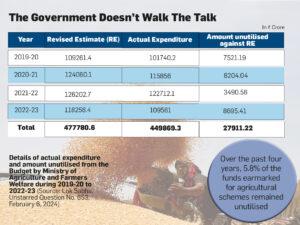

Additionally, a cumulative ₹27,911.22 crore remained unutilised by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare from the RE during 2019-20 to 2022-23. This was stated by Minister of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Arjun Munda in reply to a question in the Lok Sabha on February 6 (Unstarred Question No. 653).

In a separate answer (Lok Sabha, Unstarred Question No. 472, February 6), the minister informed the House, “The procurement of foodgrain has increased from 761.40 lakh metric tonnes in 2014-15 to 1,062.69 lakh metric tonnes in 2022-23, benefitting more than 1.6 crore farmers. The expenditure incurred (at MSP values) on procurement of foodgrains increased from 1.06 lakh crores to 2.28 lakh crores, during the same period.” Considering the number availing of MSP (minimum support price), it is a minuscule proportion of the total number of farmers in the country. The one issue that features in every draft of demands that farmer unions put before the government is revision and legalisation of MSP for various foodgrains.

MSP is the price offered by the government to farmers for 23 crops which it buys at a promised rate. This price is determined by the Union government on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). It recommends MSPs of seven cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, sorghum, pearl millet, barley, ragi), five pulses (gram, tur, moong, urad, lentil), seven oilseeds (groundnut, rapeseed-mustard, soyabean, seasmum, sunflower, safflower, nigerseed), and four commercial crops (copra, sugarcane, cotton, raw jute). In the case of sugarcane, Fair Remunerative Prices (FRP) is offered by the Centre and states give Advised Price (SAP), whichever is higher. However, in some cases, the price for the same crop may differ depending on its quality. It is sold at mandis or Regulated Market Committee Yards.

It’s all about fair price

Agriculture being a state subject, many states do not follow this method. For example, Bihar has a separate system for determining the price of a particular crop. In 2006, within months of assuming office, Nitish Kumar’s government repealed the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act in Bihar. It was said to be an attempt at ensuring better prices for farmers in the state and attracting large sums of private investment. Farmers sell produce to the state-run Primary Agriculture Credit Society (PACS), which procures at MSP. But procurement by PACS has been extremely low in Bihar, and farmers approach commission agents where the major share of crop goes.

But such is the dependence on mandis that every year hundreds of farmers—and even some agents—travel to Punjab from Bihar to sell wheat and paddy in the mandis. The administration, however, takes steps during buying season to keep such sellers away at the borders of Punjab. There are reports that some middlemen sometimes buy the produce from poor and marginal farmers and take it to mandis in search of higher prices.

The majority of farmer unions are demanding MSP be given 50% over the weighted average cost of production (CoP), which the National Commission of Farmers also known as the Swaminathan Commission, recommended. It refers to it as C2 cost. But, they say, the government is offering 1.5 times the all-India weighted average CoP (1.5 times of A2+FL).

A2 is costs incurred by the farmer in production of a particular crop. It includes inputs such as expenditure on seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, leased-in land, hired labour, machinery, fuel, etc. The equation A2+FL stands for adding the costs incurred to the value of family labour. Whereas C2 is the comprehensive cost, which is imputed rental value of owned land plus interest on fixed capital, rent paid for leased-in land plus A2+FL cost.

A committee set up by the government to look into the legalisation of MSP as well as other aspects related to the benefit of farmers after the withdrawal of the three laws is yet to submit its final report. Such is the complexity of the issue that even after the sub-committees formed to resolve other subjects have almost concluded their sittings, the MSP demand remains unresolved.

And with the general election weeks away, the standoff is again snowballing into a major political issue.