Agriculture anywhere in the world consumes a great deal of water, but Indian agriculture particularly is a water guzzler. Its usage is among the highest in the world. Satellite data and surveys of deep wells by the Central Groundwater Research Board show that the quantity of water used for cultivation in India, at 688 billion cubic metres (BCM), exceeds that in China (385.2 BCM) and the United States (176.2 BCM). About 91 percent of the water consumed in India is for agriculture, compared to 64.4 percent in China and about 40 percent in the US.

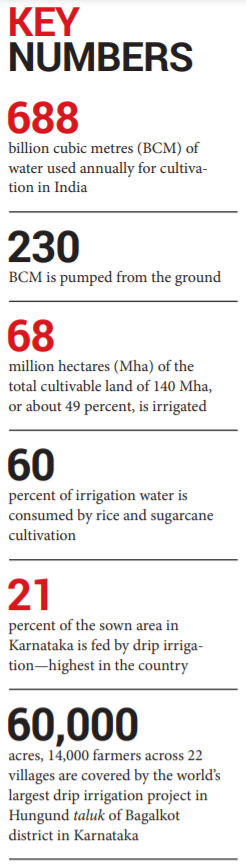

Of the 688 BCM of water used for irrigation, around 230 BCM is pumped from the ground. In 2019, there were about 30 million electric and diesel pumps. The number of tubewells has risen steeply from one lakh in 1987 to 2.6 million in 2014.

India is already categorised as a water-stressed country. A rising population has reduced the per person freshwater availability from 1,820 cubic metres (1,000 litres) in 2001 to 1,544 cubic metres (cu.m) in 2011. This may reduce to 1,340 cu.m by 2025, and still lower as India becomes the largest populated country. The share of the urban population has risen to 35 percent in 2019, from 31 percent in 2011, as per the World Bank. As the population increases, industrial activity rises and urbanisation expands, there will be increased demand for water for producing food, feed and fibre, for drinking and sanitation, and for industrial purposes.

The Green Revolution happened in parts of the country with well-developed irrigation systems, because rice and wheat varieties that could absorb higher amounts of nutrients to deliver better yields need water to do so. Further, a growing population will require expansion in coverage of the irrigation system for food and nutrition security. Of the 140 million hectares (Mha) of sown area, 68 Mha, or about 49 percent, is irrigated. The rest depends on rainfall. Of the irrigated area, 40 percent depends on canals and the rest is irrigated with groundwater.

Along with expansion of the area irrigated, we also need to reduce the water used to grow crops. Rice and sugarcane occupy a quarter of the gross cropped area (GCA), which is area sown multiplied by the number of crops harvested per year. But they consume 60 percent of irrigation water. This is because they are mainly grown in areas which are less suitable for them. Punjab grows a lot of common rice. Its productivity at five tonnes per hectare is the highest in the country. But it is hot and receives low rainfall. A lot of this water is lost due to evaporation. In the 2013-14 cropping cycle, an analysis by the Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP)—the body that recommends the procurement prices of crops—revealed that Punjab used 5,389 litres of water to produce a kilogramme of rice. Humid and rainy West Bengal needed just 2,713 litres to produce the same quantity. Punjab’s water productivity is the lowest in the country; it uses one lakh litres to produce 19 kg of rice while West Bengal produces 37 kg. As Punjab receives low rainfall, it uses up a lot of groundwater, which is pumped in abundance as electricity for agriculture is free. This makes Punjab’s irrigated water productivity (IWP) low compared with the eastern states, says a study done by agricultural economist Ashok Gulati and his team for Nabard, the agricultural refinance bank.

The same can be said for sugarcane. Much of it is grown in the sub-tropical states such as Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu though the eastern states are more suitable. For the eastern states to emerge as the rice and sugar bowls of the country, they will need to have an efficient rice procurement system and be able to attract sugar mills as well. Concurrently, procurement of rice from the north-western states needs to be disincentivised by charging for electricity. This will force Punjab farmers to adopt water-saving technologies to grow rice like direct-seeding (without flooding and transplantation) or shift to other crops.

More crop—and nutrition—can also be extracted from a unit of water with micro irrigation. The use of drips and sprinklers can minimise wastage of water. In the canal irrigation system, approximately 60 percent of water is lost while transporting to the fields due to evaporation, percolation and seepage, particularly if the canals are not lined. They take up a lot of land, cause water-logging and make the soil saline. Farms at the tail end tend to receive less water than those at the head.

Micro irrigation is more efficient, particularly drip irrigation, as it delivers just the required amount of water to the root zone. Dissolved nutrients can also be delivered in the precise amounts. Less humidity results in lower incidence of pests and diseases and water is made evenly available to plants across the field, unlike in flood irrigation, which leads to uneven distribution, resulting in uneven yield from the same field.

Micro irrigation has been promoted in India since the early 1990s. Maharashtra-based Jain Irrigation has been a pioneer though Netafim of Israel has been the global leader. ‘More drop per crop’ used to be the slogan then. Given his penchant for changing nomenclature, Prime Minister Narendra Modi changed it to Per Drop More Crop in 2015-16. As per the CACP’s Kharif report of 2021-22, Karnataka has 21 percent of its sown area covered by micro irrigation, followed by Gujarat (15 percent), Andhra Pradesh (14 percent), Tamil Nadu (14 percent) and Maharashtra (12 percent). CACP observes that the progress of micro irrigation is comparatively better in water-scarce states, while Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have a very low share of four percent. “As water crisis is looming large, it is imperative to expand area under micro-irrigation in all states,” the report says.

Micro irrigation projects have been implemented on individual farms. Horticulture farmers like those growing grapes, pomegranates or bananas are most keen. Micro irrigation equipment is heavily subsidised by the government. In Karnataka, the government reimburses 90 percent of the investment for farmers owning up to five acres, the share of the central and state government varying as per the caste of the beneficiary (non-SCs/STs get a lower share from the central government). The subsidy for farmers owning in excess of five acres is lower.

In Maharashtra no new sugar mill licences are given unless the farms that supply cane to them are entirely drip irrigated. The sugar mills guarantee repayments to the drip irrigation companies from cane dues to farmers.

As governments bear most of the cost, it is more efficient to have community-wide lift and drip irrigation projects. They can cover wide swathes of land and make scarce water available to a large number of farmers in a short time. Karnataka is implementing six such projects. The one across the Krishna river in Bagalkot district’s Hungund taluk is touted as the world’s largest drip irrigation project. It covers 60,000 acres and 14,000 farmers across 22 villages. The project was awarded to Netafim and Jain Irrigation and was commissioned in 2017.

Micro irrigation is more efficient, particularly drip irrigation, as it delivers just the required amount of water to the root zone. Dissolved nutrients can also be delivered in the precise amounts. Less humidity results in lower incidence of pests

The videos uploaded on YouTube by the two companies claim huge savings in water, fertiliser and energy, besides substantial increase in crop yields. They speak glowingly of farmers prospering by growing cash crops and preferring to stay back in the villages rather than migrating to cities. A note on the project uploaded on the website of the water resources ministry says that though it cost ₹750 cr, amounting to 25 percent more than a comparable and conventional canal irrigation scheme, there is 90 percent increase in area irrigated. Therefore, the cost of irrigation per hectare is ₹3.13 cr compared to ₹2.5 cr for a conventional project.

The entire irrigation project is a closed loop, pressured system. Water is lifted from a reservoir and pumped into a sump, where it’s filtered for silt and debris. It is wirelessly controlled with instrumentation that regulates supply based on feedback from pressure and flow sensors. The entire area is divided into zones of about 1,200 acres and further into 10 subzones, to which water is supplied in shifts, the maximum being up to 72 minutes a day at a rate calibrated for rainy and winter seasons. Water user associations are supposed to collect the maintenance charges of ₹1,000 per acre.

But what’s the ground reality? Ravi Sajjanar, 31, the founder of Hunagunda Horticulture Farmers Producer Company, says he is “very disappointed”. He owns 50 acres and supplies chillies on contract to ITC and Olam. His organisation has 1,000 members, he says, who own 3,640 acres across 18 villages in the footprint area. Some of the farmers have got 40 percent of the promised supply, he says, some not even that. Farmers who invested in adapting crops to the new irrigation system lost money, he observed.

Rafiq Mulla, 40, of Sullibhavi village in Hungund taluk said he never got the “correct” amount of water even once. The pipelines broke and were not repaired. The trenches that were dug to lay the pipes were not covered. There is no assured supply in August and September when water is most needed. Mulla grows pigeon pea (tur) and chillies. Abdul Khader Jeelani, 33, and Mahantesh Patil, 45, also of Sullibhavi, had the same complaints. “The project is not a success,” Patil said.

Sanmesh Hosur, 28, an advocate, whose father has a farm in Chittargi, says they do not get water when needed. The pipes burst because water is supplied at a pressure higher than they can bear, he says. Basuraj Shankarappa Tatod, 46, of Sullibhavi who has a little over one acre of land, says he has not got water since the inception of the project. He could harvest just 50 kg of maize from his 1.5-acre farm in the past season. “We are tired of complaining,” he says. Of the many farmers spoken to, only Shankargroud Dadmi of Timmapura said he was satisfied with the project and was able to harvest two crops a year.

Company executives VL Nikam, Jain Irrigation’s VP (Projects) for Karnataka, and Girish Deshpande, who looks after six projects in Karnataka for Netafim, have their own sob story. They say farmers have not been able to switch mindset from rainfed irrigation to micro irrigation.

They don’t have the patience to abide by the supply schedules. Some farmers tap the mains illegally to draw extra water, which reduces the pressure in the system and deprives others. There is no sense of ownership, because the equipment was provided free. Even user charges are not collected. The laterals or pipes in the fields are damaged during land preparation for sowing and farmers blame the companies as they have responsibility for operations and maintenance for five years.

The drip pipes need to be protected from rodents, but farmers don’t follow advice. The companies say they have engaged security services at enormous cost to prevent vandalism, but it has not helped. Complaints lodged with the police are not acted upon under political pressure. Farmers are yet to receive compensation from the government for land acquired for the pump house and other common utilities.

It’s clear after assessing the facts on the ground that farmers need to abide by the discipline that community-based projects require for the benefits to percolate down the entire chain of beneficiaries.

The executives of the company say that they are applying the Ramthal learnings to the other projects under execution. Making farmers aware is critical for project success, they say. They have engaged external agencies like NGOs and government horticulture and agriculture departments. Farmers are being trained in cultivation of profitable cash crops with the appropriate package of agronomic practices.

The drip pipes need to be protected from rodents, but farmers don’t follow advice. The companies say they have engaged security services at enormous cost to prevent vandalism, but it has not helped. Complaints lodged with the police are not acted upon

The Ramthal experience reminds one of India’s programme to end open defecation where it was found that mere construction of toilets on a major scale would not end the practice. Behavioural change and sincerity of purpose are needed. Micro irrigation must be seen not only as a necessity for areas without irrigation, but also for those which have it. If electricity were priced properly in Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh and preference was given to the procurement of rice from the eastern states, the north-western states would be compelled to embrace micro irrigation and grow the crops that India needs—oilseeds and pulses—which are also socially useful because they consume less water and subsidised urea fertiliser.

For Current Affairs, Follow Tatsat Chronicle on Facebook, Twitter and get connected to us on LinkedIn