A law which Parliament approved in early April to replace a 102-year-old piece of legislation and give legal backing to the collection of measurements of convicts and other persons is so wide in its ambit regarding both personal data points that can be collected and persons covered that it seems designed for a regimented society rather than for the exercise of liberty. The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022, is so sweeping in its scope and span that it has all the hallmarks of legislation befitting a police state.

Yet, the bill was rammed through by the government with very little pre-legislative consultation or debate in the House. The government introduced it in the Lok Sabha on March 28 and got it passed on April 4 by voice vote, ignoring the Opposition’s demand to have it scrutinised by a parliamentary committee. The Rajya Sabha approved it two days later in a similar manner and on April 18, the government notified it in the Gazette of India as an act.

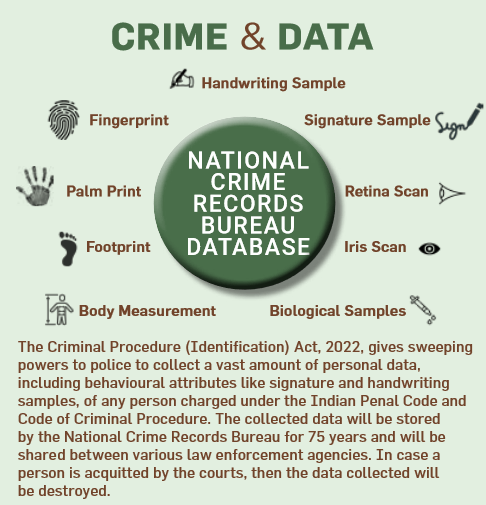

The measurements that the new law allows to be collected are extensive: fingerprints, palm prints, footprints, photographs, iris and retina scans and physical and biological samples and their analysis. It also includes ‘behavioural attributes’ like signature and handwriting or any other examination under Sections 53 and 53A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). Section 53 provides for medical examination of an arrested person on the request of a police officer with the intention of obtaining evidence of the commission of the offence the person has been charged with, while Section 53A allows the police to get a person charged with rape to be medically examined.

The new law also allows measurements to be collected of any person that the State chooses. This includes those convicted of any offence, arrested in connection with any violation of the law, detained under any preventive detention law or ordered to furnish bonds of good behaviour. The bonds are required to be furnished under sections of the CrPC by those who have breached public peace, distributed seditious material, concealed their presence preparatory to committing a crime or are habitual offenders.

The law is sweeping compared to the British-era law it replaces. The Identification of Prisoners Act, 1920, allowed fingerprints, footprints, and photographs to be collected only from convicts, those directed to furnish bonds of good behaviour or arrested for offences punishable with a jail sentence of one year or more. The new law has no such compunctions, except that it restricts the collection of biological samples to those charged with offences against women or children or crimes carrying a jail sentence of seven years or more. Other persons required to give measurements “may not be obliged to allow the taking of their biological samples”. It is not an express prohibition, which leaves it open to interpretation by the investigating agencies.

Updation of the colonial law was needed to account for scientific advances in forensics. In 1980, the Law Commission had examined the 1920 law in detail and had suggested improvements

This is a “tremendous” expansion from the colonial law, says Apar Gupta, executive director of the Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation and a lawyer who writes on the interplay of technology and democratic rights in India. He says that even those charged with petty offences like traffic violations, jay walking, or even being caught in a public park after 8 pm can be directed to give their personal measurements. Speaking on the bill in the Rajya Sabha, Congress leader and former Home Minister P. Chidambaram asked whether there was any political person, trade unionist, social activist or progressive writer who had not violated any law. He ridiculed the sweep of the act. Even those committing petty offences like a bus driver in Delhi straying from the bus lane, or a breach of the prohibition of unlawful assembly (Section 144 of the CrPC) can now be asked for measurements. Chidambaram also pointed out that politicians, who routinely court arrest or are detained temporarily, might also fall within the ambit of the new law. In response, Home Minister Amit Shah gave a verbal assurance that political detainees would not be required to give measurements if there were no criminal charges and the rules would provide for this.

In an impassioned speech in the Rajya Sabha, Trinamool MP Mahua Moitra chided “an elected government which claims to be more nationalistic than the British” for bringing in a law that is “more intrusive, that collects more data than the original law and has fewer checks and balances and fewer safeguards than even the British-era law did”. The law “is for a police state,” she said, and the “vagueness and overbreadth of several provisions are extremely concerning”.

Updation of the colonial law was needed to account for scientific advances in forensics. In 1980, the Law Commission had examined the 1920 law in detail and had suggested improvements. The commission had done so after the Supreme Court, in State of UP v Ram Babu Misra, in February 1980 held that the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, does not allow a magistrate to direct a person under investigation for an offence to provide their handwriting specimen, though a court could direct a person facing proceedings before it to provide it.

The commission recommended that palm impressions, handwriting specimens, signatures and voice samples be added to the list of measurements—fingerprints, footprints and photographs—that could be collected under the 1920 Act. But it was alert to the “conflict between the interest of the citizen to be protected from invasion of his physical privacy and the interest of the state to secure evidence for investigation and prosecution of crimes”. It observed that “a balance has to be struck between the rights of an individual and the imperative need to prevent crime and to punish it”.

Such balance is missing in the new law, say its critics. Chidambaram faulted it for allowing the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), as the repository of the measurements, to share and disseminate the records with “any law enforcement agency”, which has not been defined, and could include any organ of the government. A panchayat, he said, would be such an agency as it administers panchayat law. Experts have pointed out that making records widely available would be very intrusive and without any checks and balances.

The government is within its rights to collect the expanded list of measurements. The Law Commission in its 1980 report had said that the Supreme Court in many judgments had held that collection of “non-communicative” evidence does not violate the Constitution. The criminal investigation is an exception to privacy law, but even that exception has limits. In 2010, in Selvi v State of Karnataka, the Supreme Court prohibited involuntarily subjecting a person to narcoanalysis, polygraph or lie detector tests or brain mapping or Brain Electrical Activation Profile (BEAP) as it would amount to testimonial compulsion and a violation of the right against self-incrimination. To a question from Chidambaram whether the law would allow such tests, the home minister replied that it would not, and the rules would prohibit them.

Criminal investigation is an exception to privacy law, but even that has limits. In 2010, in Selvi v State of Karnataka, the Supreme Court prohibited involuntarily subjecting a person to narcoanalysis

Critics of the law also say that it violates the Supreme Court’s 2017 judgment in Justice K S Puttaswamy V Union of India, where a nine-judge bench unanimously affirmed that privacy was a fundamental right and an intrinsic aspect of dignity, autonomy, and liberty. They had said that any legalised erosion of the right to privacy must satisfy a legitimate state aim and the means adopted must be proportionate to the objective sought to be achieved. In Chidambaram’s view the new law violates the Puttaswamy judgment. On the face of it, seeking these measurements from any person arrested or detained for violation of any law does not meet the test of proportionality or legitimate state aim.

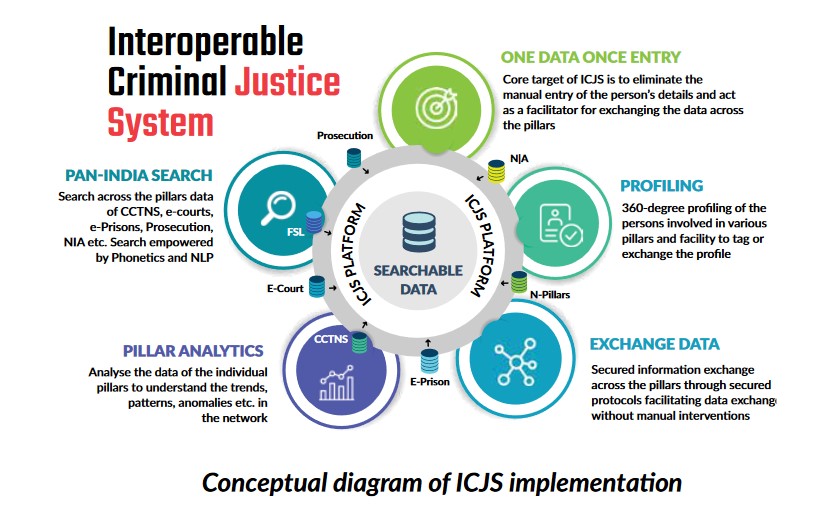

However, the home minister disagreed. He said the law did not violate the Puttaswamy judgment as there was a need to improve the conviction rate. As per the NCRB, only 44% of murder trials completed in 2020 resulted in convictions and for human trafficking it was 10.6%, while for rape it was 39%. Shah said lack of evidence resulted in prolonged litigation as courts sought more and better evidence. This law would strengthen the criminal justice system. Reliance on forensics would eliminate resorting to torture and extraction of confessions. It was part of a broader modernisation project that has seen digital technology initiatives like all 16,390 police stations in the country being connected toCCTNS (Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems).

The home minister allayed fears of data leakage, despite plenty of evidence available in the public domain. He said that the NCRB would securely store the data and the records, when disseminated, would leave electronic trails. He said the law was brought in at the suggestion of experts, but he did not explain the hurry in enacting it and why it could not be scrutinised and improved upon in a parliamentary committee. The DNA Technology (Use and Application) Regulation Bill, 2019, was referred to a standing committee on science and technology, but the bill has not been taken up for enactment even though the committee has given its report. Nor did Shah say why the records had to be kept for 75 years, beyond the average life expectancy of Indians, which is about 70 years. For most of his 50-minute reply, Shah attacked the Opposition for privileging the human rights and privacy of criminals, as he put it, over those of the victims. Freedom has its limits; it cannot be used to curb the freedom of others, he said. The government was concerned with the rights of the majority that was law-abiding. By harping on human rights, the Opposition was tying the hands of the police and “throwing it in a swimming pool” while expecting it to bring “gold medals”. He decried the tendency of the Opposition to mistrust the government.

The home minister said the law was brought in at the suggestion of experts, but did not explain the hurry in enacting it and why it could not be improved upon in a parliamentary committee

This was in reference to Moitra’s mention of the Unlawful Activities Prevention (Amendment) Act during the debate, when she said she wished she could trust the government. During a debate on the UAPA Bill in July 2019, she had warned that the government would use it against those it disliked. That Bill allows an individual, and not just an organisation, to be designated as a terrorist, and put in jail. It makes bail virtually impossible to obtain. She said her apprehensions were right. Between 2016 and 2019, about 5,000 cases were registered under UAPA and about 7,000 persons were arrested, but the conviction rate was 2.2%.

In his reply to the UAPA Amendment Bill, Shah had, as with the criminal identification bill, sought “unanimity” of support in the House. He had dwelt at length on terrorism and why the amendment was necessary to curb it. Then, as now, he had justified the amendment by saying the United States, the EU, Israel, and Pakistan had laws to declare individuals as terrorists. But the fears of the Opposition were not misplaced. UAPA has been used against students protesting against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA). Dalit intellectuals and those working among tribals like the late Fr. Stan Swamy have been branded urban Naxals (he was locked up until his death in a Mumbai hospital, where he was shifted on court orders).

Scientific techniques do greatly help in detection and prosecution of crime. The United States Department of Justice, for instance, says on its website that new-generation identification which the criminal justice division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has deployed is a step up over the automated fingerprint identification system. It provides the criminal justice community, it says, with the world’s largest and most efficient electronic repository of biometric and criminal history information. But there are safeguards. The collection and storage of such data is governed by the US Privacy Act.

In September 2021, the Karnataka assembly passed a bill to allow collection of blood, DNA and voice samples and iris scans of those convicted or arrested

Fingerprints, for instance, can be collected only of “wanted persons”, that is, those who have committed an offence or been identified with an offence classified as a felony or serious misdemeanour; those against whom a temporary felony charge has been entered; juveniles charged with the commission of a delinquent act that would be a crime if committed by an adult; members of violent criminal gangs or terrorist organisations; and unidentified persons who are deceased, or living but whose identity has not been ascertained. The US National DNA index system mentions the categories of individuals covered, and the agency that maintains DNA samples. Moitra pointed out that the EU has strict laws governing privacy, including purpose limitation, that is, the measurements can be collected for a specific purpose and used only for that purpose. The Indian law has no such restrictions and there are no signs of this government enacting a suitable data protection law.

The fears expressed over the collection of an expanded list of measurements should also be seen in the context of policing practices and police attitudes in India. There is a tendency among the police to see certain communities like the Pardis, whom the British had designated as a criminal tribe, as having a greater propensity for crime. The 2019 report of Common Cause, a Delhi-based NGO, on the “State of Policing in India” said that 14% of police personnel surveyed felt that Muslims were “very much” prone to committing crimes, while 36% felt they were “somewhat” prone to committing crimes. The report was based on a survey of 12,000 police personnel and an additional 10,595 of their family members. It was prepared by the Lokniti programme of the Delhi-based Centre for Study of Developing Societies, which has a track record of credible surveys. Though this is not an argument against advanced crime investigation techniques, it makes a case for policies and training to scrub out police biases.

Some states have been a step ahead of the Centre in ‘upgrading’ the 1920 law. In September 2021, the Karnataka assembly passed a bill to allow collection of blood, DNA and voice samples and iris scans of those convicted or arrested for offences punishable with a jail sentence of one month or more (from one year earlier), or held under any preventive detention law. The authority to order such collection was extended from magistrates to superintendents of police. The object clause of the bill says the purpose is “effective surveillance” for prevention of crime and breach of peace.

The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022, is yet another cog in the gigantic surveillance machinery that is being built in India by linking various databases under the guise of developing a digital ecosystem. The latest law is part of the Interoperable Criminal Justice System (ICJS), which received the government’s nod in February this year.