India is on the cusp of becoming a digital society. Decades of investment in the telecommunications and information technology sectors, in conjunction with global factors, have brought us here. The Government of India, over the past decade, has been building information, digital, platform, and surveillance infrastructures such as Aadhaar, UPI, Digital Locker, GST Network, and various other digital platforms or stacks to power a data economy. The core idea behind this centralised digital infrastructure is to collect all the data of citizens and share it with the private sector to turn us into consumers. India is adapting to global changes in capitalism with the dawn of the fourth Industrial Revolution or the age of surveillance capitalism. The keystone of the fourth Industrial Revolution is 360-degree data profiles of people.

The digital infrastructure that will ultimately drive the surveillance capitalism model is not entirely being built by the government. It follows the public-private partnership model, involving the private sector—a policy of the Government of India since liberalisation in 1991. The private sector, led by its representative, Nandan Nilekani, is not only proposing these systems but also building them by calling themselves, volunteers. These platform infrastructures are also referred to as the digital versions of public goods and the APIs (Application Programming Interface) to access these platforms as information highways. The public-private partnership has always been the model for privatisation of the commons, whether it is real-world public goods like airports, seaports, and railways, or now, our personal data, which is being treated as commons.

In this information age, information is the currency. When data is compared to oil what people might not be entirely explaining is that it is wealth. The question then to ask is whose wealth? It’s the data holders’ wealth; in this case, we the people of India. As the representative of the people of India, the Government of India is staking a claim to ownership of people’s personal data. It is with this idea that the government is forcing people to part with their personal data, to be stored in common national digital infrastructure. This model of digitisation also involves the creation of a new credit economy, primarily led by gathering everyone’s personal data.

Digitisation as a process serves both the economic and political interests of those in power, irrespective of their political ideology. Depending on which department of the Government of India wants to collect your personal information, there are multiple interests and groups that it can serve. All of these interests intersect at Aadhaar, the foundational digital identity, which powers surveillance capitalism in India. The digital identity as a digital artefact was designed to power this entire economic ecosystem to allow consumer acquisition electronically, to prove their identity, to authorise transactions using e-sign, and to share data with e-KYC, to name a few elements. The scope and span of exploitation of personal data for commercial gain are enormous. The contours of the emerging surveillance capitalism are yet to be discerned in detail and its impact fully ascertained.

National security alibi

The big push for building surveillance databases came after the 26/11 Mumbai terrorist attacks. It shaped some of India’s digitisation policies and created a new digital infrastructure. The push for the National Population Register and Aadhaar coincided and led to increased data collection by various arms of the government. For example, national security interests provided levers to the Ministry of Home Affairs for building a series of surveillance infrastructures such as the National Population Register, NATGRID, and the Crime and Criminal Tracking Networks and Systems (CCTNS). The Department of Fisheries started issuing biometric identity cards to fishermen and started registering all fishing boats following the attacks.

Digitisation as a process serves both economic and political interests of those in power, irrespective of their political ideology. Depending on which department of the Government of India wants to collect your personal information, there are multiple interests and groups

The legal battle against increased data collection by the Government of India with plans to link every aspect of our personal lives to Aadhaar was important for individual freedoms. It helped people win an important right in this digital age—the fundamental right to privacy. It tried to put brakes on the exponential expansion of Aadhaar. The Puttaswamy Vs Union of India (2017 and 2018) judgment put limitations on both government and private sector use of Aadhaar. What was initially conceived as an identity to provide welfare to the marginalised was being expanded everywhere in our lives. The Supreme Court tried to stop this by restricting the government to only using it for delivering welfare schemes and taxation with no access to data for the private sector. Unfortunately, the Narendra Modi-led government was not interested in following the Court’s order and devised new ways by amending the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) to allow private sector access to Aadhaar data as a money bill. Further, the government brought these new rules under PMLA for sharing Aadhaar APIs by terming them “good governance” practice.

This legislative sleight of hand allows the Modi government to circumvent the Puttaswamy judgment without providing any explanation to India’s citizens about the need for a unique digital identity, except for receiving government subsidies. The answer to this probably lies in how the government wants to use Aadhaar to build technology architecture for India. The National e-Governance Division (NeGD) has a flagship project to build what it terms India Enterprise Architecture. It’s a unified technology platform that will interlink all government databases using Aadhaar to give a 360-degree view of citizens to the government.

Introduced as State Resident Data Hubs (SRDH) by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), the project quickly transformed into State Enterprise Architecture in Andhra Pradesh. Leading this transformation was the then UIDAI chairman, J Satyanarayana, proposing a 360-degree profile database for everyone in Andhra Pradesh, calling it People Hub. Under Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu and Satyanarayana, Andhra Pradesh collected everyone’s personal details regarding every aspect of their life and interlinked these databases using Aadhaar. The privacy implications of this project were disastrous when Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party used this data to profile voters during the 2019 general election.

The lack of legal protection for personal data even with a fundamental right to privacy stems from the government’s interest in promoting a data economy. Any push to penalise companies for lacking safeguards will be seen as a strict regulation, hurting business and investor sentiments. In the entire history of digitisation in India, no private company, including Cambridge Analytica, has been penalised for data breaches. Investigations might have been opened but to no end and the India Computer Emergency Response Team does not deign to even respond, let alone investigate cyber incidents when they are brought to its notice.

The India Enterprise Architecture is the final phase of digitisation under the Digital India project. It interlinks several segments of national digital infrastructure, including State Enterprise Architecture, to create a giant inter-connected governance platform

Myth of real-time governance

The rationale for interlinking various government databases to build 360-degree profiles of citizens was justified by a new form of governance, termed “real-time governance”. Coined by Satyanarayana, this was a form of predictive governance, where the government collects citizens’ entire personal data and provides them everything they need before they ask for anything. In simple terms, it means mass surveillance by the State. Unfortunately, when presented with evidence of the problems with State Resident Data Hubs, the Supreme Court did not look into this digital infrastructure as part of the Puttaswamy judgment. This is now coming back in its full glory with the India Enterprise Architecture.

The India Enterprise Architecture is the final phase of digitisation under the Digital India project. It interlinks several segments of national digital infrastructure, including State Enterprise Architecture, to create a giant inter-connected governance platform. An exercise to standardise all governance activity with multiple digital standards will power this technology architecture. True to its name, the India Enterprise Architecture is a national architecture that will not only unify all governance structures but will also centralise them, giving the central government enormous control over its citizens and making India a full-fledged surveillance state. This push for a unified architecture is to enable a single digital market for private companies that want to be part of the data economy.

This final phase of digitisation marks the completion of a process that started decades ago, and the technology architecture determines how Indians will be impacted by this. The complex architecture allows third-party, private players to use Open APIs to access citizens’ personal data for governance and private commerce. But for this to happen, the government first needs to collect all of our data and centralise it. Some of the sub-systems in this ecosystem of technology databases and platforms include the National Digital Health Ecosystem, the National Urban Innovation Stack, the India Digital Ecosystem for Agriculture (IDEA), the Integrated Criminal Justice System, the Public Credit Registry, and e-voting infrastructure, to name a few prominent ones.

The data protection law is also expected to put a rubber stamp on the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, another structure which will allow you to provide electronic consent to share your personal data

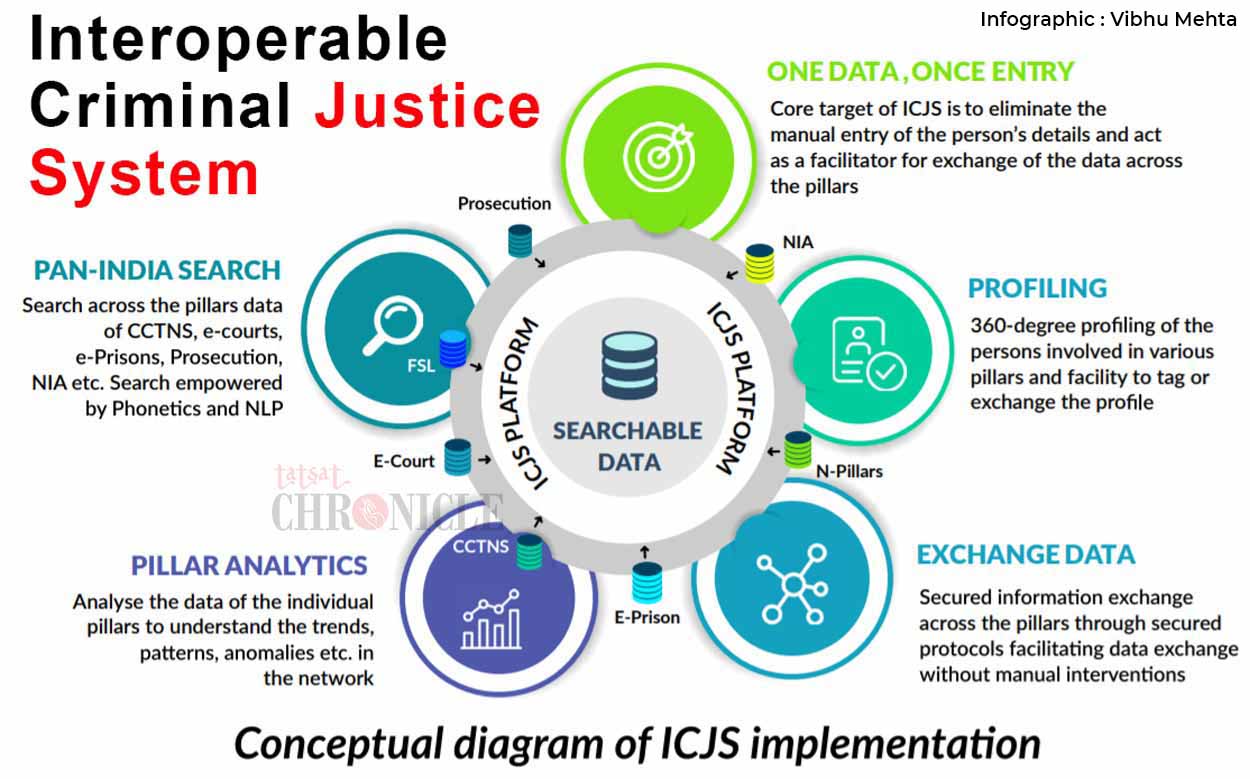

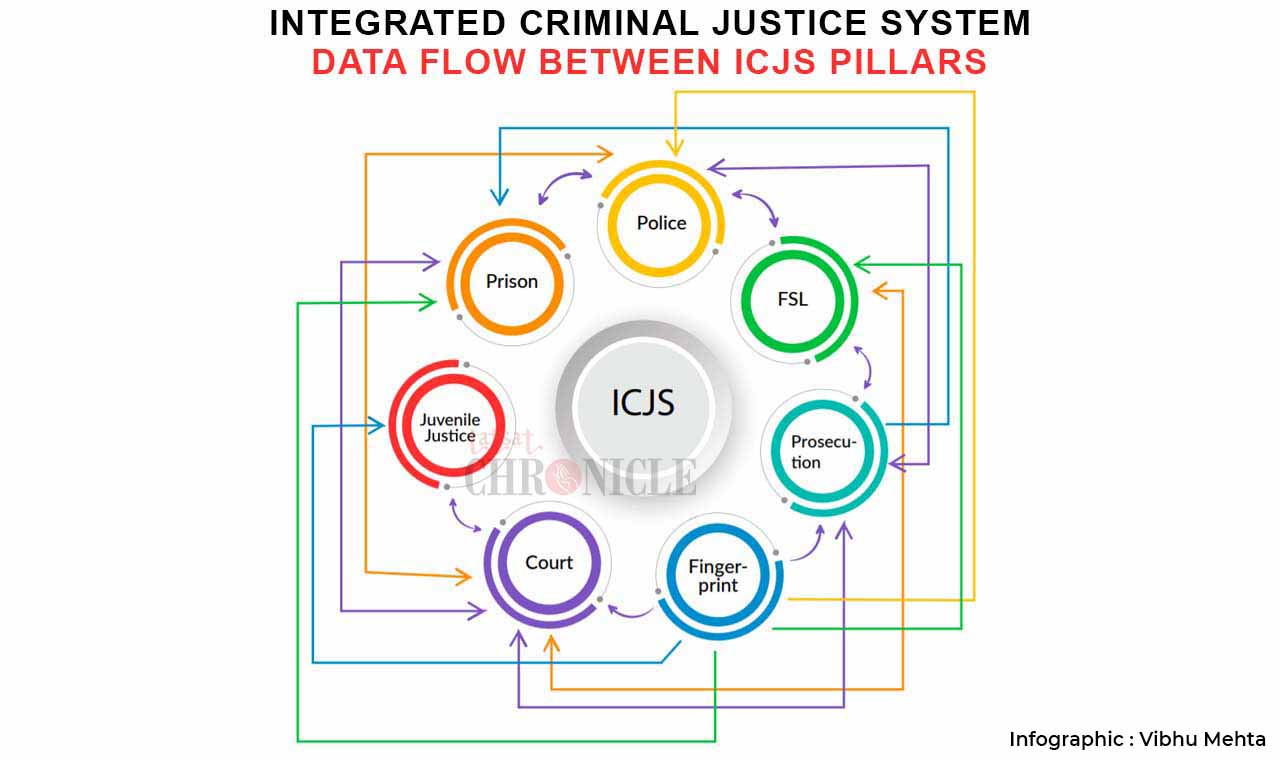

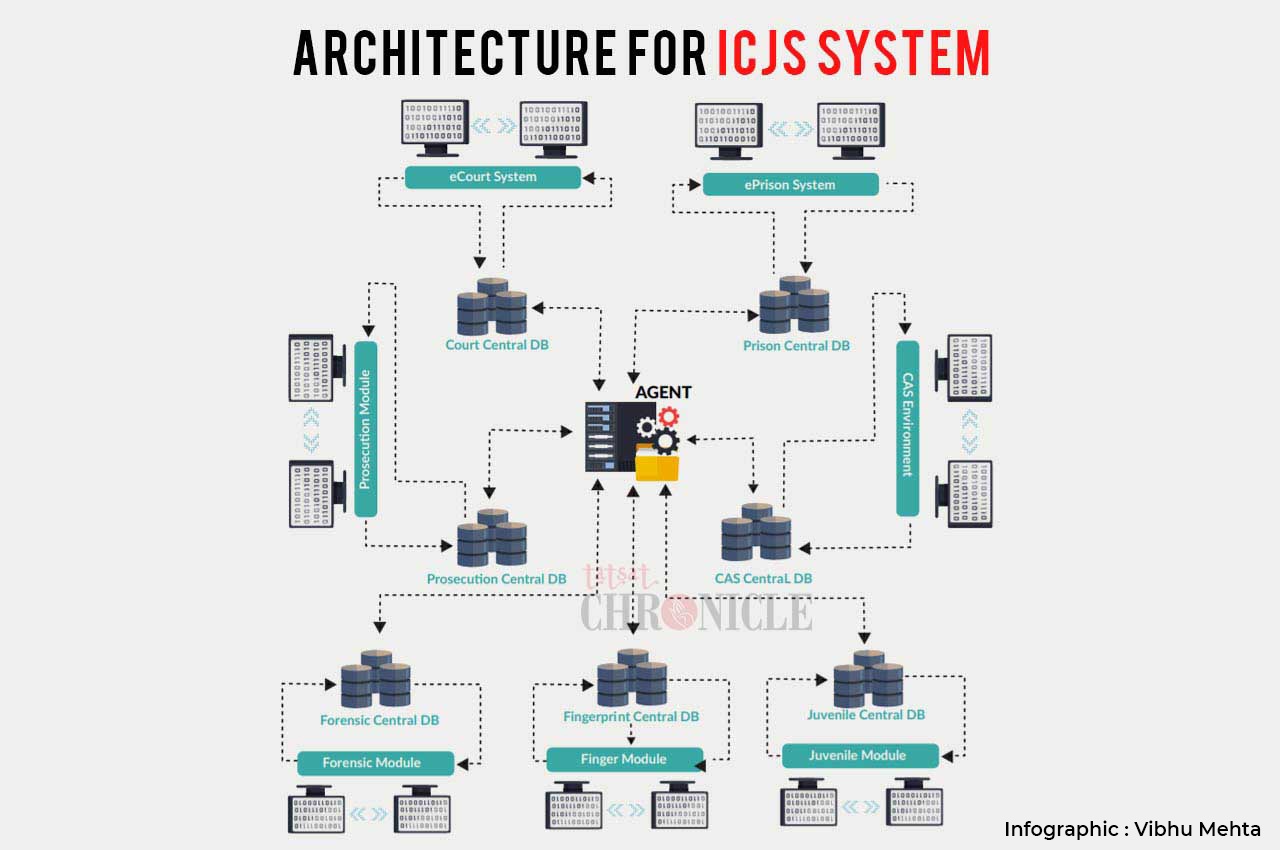

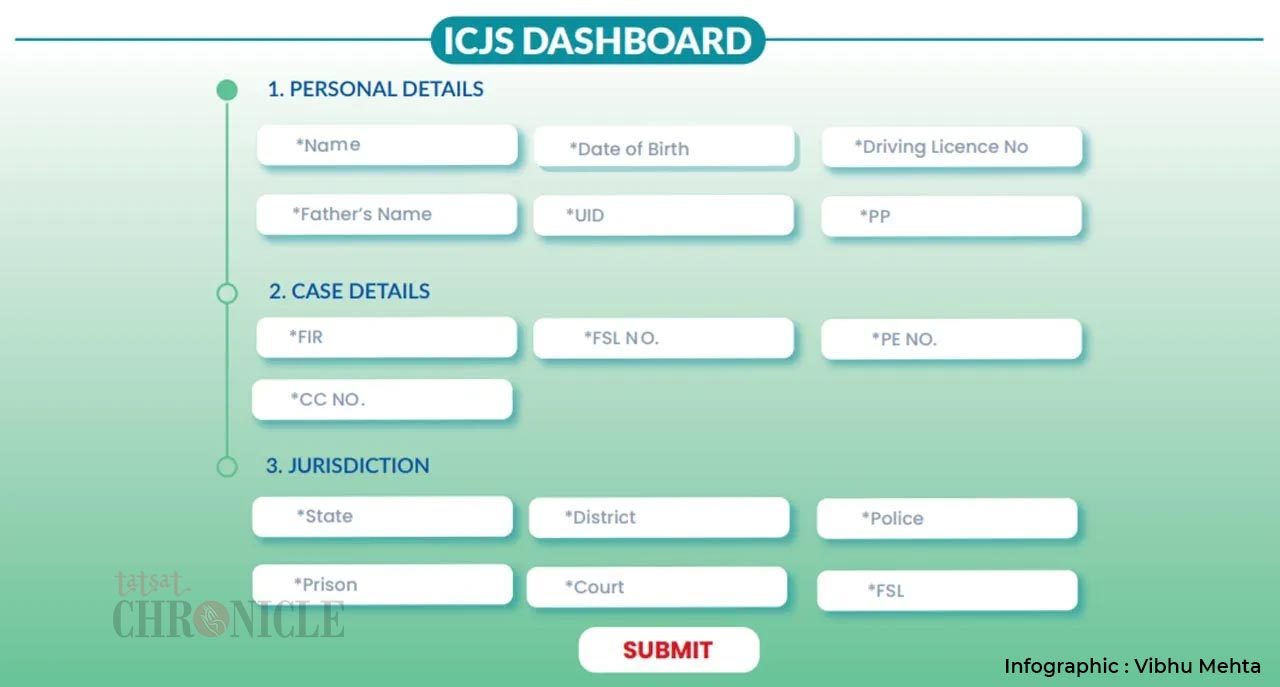

At first glance, it might appear that this digital infrastructure is being built in an isolated manner, but the process of interlinking them and centralisation is giving away control and placing it in the hands of the executive. Consider the case of the Integrated Criminal Justice System, which will integrate information systems of e-courts and e-prisons with that of police (CCTNS) at the Ministry of Home Affairs. This push is being done to break the information silos that exist between the arms of the executive and the judiciary. But how does one explain the concept of separation of powers at the information level? These silos exist for a reason and are designed into every functioning democracy in the world. Decentralised information at various levels of our democracy is a feature and not a problem that is meant to exercise separation of power between the executive, the legislature, and judiciary.

The Integrated Criminal Justice System is a complex 360-degree profile architecture in itself, where several other surveillance infrastructures such as the National Automated Facial Recognition System, the National Automated Fingerprint Recognition System, the National Economic Offenders Registry, the National Missing Children’s Registry, and the National Sexual Offenders Registry, etc. are linked. It also interlinks with other national infrastructure like Vahan-National Transport Registry, from where data about vehicles and licences can be pulled. All of this is a tiny component of the India Enterprise Architecture, which intends to digitise every aspect of our lives and give this information to the government and the private sector. It is a panopticon designed for economic and political control that will underpin the surveillance capitalism.

Each individual digital infrastructure has its own standards and architecture and is digitising individual sectors. In all fairness, one can argue digitisation will help increase economic activity, it will bring transparency and accountability. But the flip side of the coin is increased surveillance, an increase in government control over citizens, and a greater digital divide that we are already seeing. The extent to which the government gets empowered to control every aspect of people’s lives is worrisome. The question is how and what sort of accountability systems are being built into the architecture and standards. Flaws in software design can have a disastrous impact on people’s personal and economic lives and they might not even understand why it is happening. Technology can fail in so many ways, categorising can only happen after the incidents. In the case of Aadhaar APIs, there are over 100 ways an error can occur as per UIDAI’s own manual.

Presenting a fait accompli

A data protection law is on the way and is supposed to offer some comfort to citizens in this data economy. It is supposed to safeguard our interests and put in some checks and balances in the data economy. But I do not share this optimism due to a range of factors, as the data protection law is more about the economy and not about citizen rights anymore. It protects the data that has already been forcefully collected from us, whether it is Aadhaar or our financial or health data to be stored in databases protected behind 13-foot walls. There is no choice but to share your data with the government, which retains the discretion to do whatever it wants. This is one reason for the lack of a precise definition of ownership over personal data by the government.

The data protection law is also expected to put a rubber stamp on the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, another structure which will allow you to provide electronic consent to share your personal data

The data protection law is also expected to put a rubber stamp on the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, another structure that will allow you to provide electronic consent to share your personal data from these national infrastructures to private apps through APIs. A marvellous design where you will be forced to share your data first and asked for permission later when you share it again with the private sector. Section 35 of the draft data protection law is the key clause, which allows this to happen because exemptions are used to collect and use data for any reason by the Government of India.

The government and the Indian IT sector are promising to empower citizens through data, by forcefully taking it away from them. In reality, it’s disempowering them in the process. Aadhaar was promised to empower everyone who received this digital identity, instead, we witnessed a nation-state hounding for personal data in the name of finding duplicates. People have been disempowered literally when Aadhaar was used to remove them from electoral rolls being called duplicates in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated Indian and global efforts for even greater digitisation. It also showed us the digital divide in our digital society, where only certain classes of people can participate through technology design. Technology is a force that is accelerating this digital divide and it is clearly visible in India’s Covid-19 vaccination programme, where another digital infrastructure called CoWin with its Open APIs has caused havoc. These digital-only processes, while seeming revolutionary, are actually causing tremendous problems, which neither the government nor the IT sector is willing to accept.

Industrialisation across generations has caused a series of problems for society, whether it is railroads, cars, or even electricity. Society adapted to these innovations and put checks on them in the form of speed-breakers and circuit-breakers when they tended to overload and cause damage. But without any checks and balances, both in the design of these digital systems and in law, Digital India is a train without brakes at the moment that doesn’t care what lies ahead on the tracks. It will just keep racing ahead, leaving behind a trail of destruction that will become visible in the future.

The writer is a researcher with the Free Software Movement of India.

By Srinivas Kodali