It is the 48th day of the NREGA Sangharsh, or agitation, at Jantar Mantar, the well-known protest site in Delhi. One set of speakers from West Bengal is making fiery speeches in Bengali, demanding dearness allowance arrears, filling of vacancies in government schools, colleges and offices, and permanent positions for contract employees. Another group wants reversion to the old pension scheme for teachers and school staff.

The third set are National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) workers. Every week, a batch from one state protests and then passes on the baton to a batch from another state for the next week. They intend to do this for 100 days. When I visited them, a group of 80 from Chhattisgarh had yielded place to 42 from Gujarat. They had been preceded by batches from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, West Bengal and Jharkhand. In the evenings they retire to a rainbasera, or shelter for the homeless, in East Delhi. On the day of my visit, their lunch was contributed by a donor.

Rap from app

The workers have been drawn to the capital by the requirement, made mandatory from the beginning of this year, for photos of each worker to be uploaded twice a day, one during each half, from geo-tagged worksites as proof of attendance. NREGA Mates, or women employed by panchayats, are required to do the uploading via an app called the National Mobile Monitoring System (NMMS) through their smartphones. This was mandatory at all worksites with more than 20 workers since last May. From this year, it has been extended to all worksites.

The workers want this requirement to be withdrawn. If the photos are not uploaded, they do not get paid despite working. Thakur Prasad of Bankesma village in Udaipur block of Chhattisgarh’s Surguja district says he has been doing NREGA work for many years. He was marked present for seven of 14 days he worked this year. His wife worked for as many days but there is no evidence of it. According to him, the app is acting up and he says, “Gapla ho raha hai” (something is fishy). They had levelled the field of a farmer who belongs to the Korbo Primitive Tribal Group (PTG). This is among the list of approved NREGA works. Prasad had worked for 40 days last year and was paid in full, though he cannot recall how much the amount was. With NREGA wages and his rice harvest from a family plot (of 20 khandis or 400 kg last year), he feeds his family of six, including four children.

Kanta Devi from Ajmer,Rajasthan

The main grievance of Kaanta Devi is the NMMS app and provision of online attendance imposed on the NREGA workers. She says that due to this workers are not getting paid their legitimate wages as they get low attendance against the work… pic.twitter.com/GUNs3etJ5f

— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) March 30, 2023

Dharamsai from District Surguja, Block Lundra, Panchayat Bilhama, Chhattisgarh – he has still not been paid for 38 work days done back in Nov & Dec 2022 – was sent for #NREGA work to forest department area in Dhourpur – online attendance not marked properly pic.twitter.com/x1k3TpJCXq

— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) April 10, 2023

Name: Rupi

Rupi has worked for 20 years. The #NREGA work site is 3 km away from her home. She has said that if the photo and network issues occur during attendance her labour for the day goes to waste as she is not paid at all. pic.twitter.com/Qp3N2MQpqj— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) March 30, 2023

Vandana Tirkey, a social worker from Lundra block in Surguja, associated with the Right to Food campaign, says people like Prasad live in forested areas where Schedule 5 of the Panchayat (Extension of Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA) applies. The Act is meant to protect the traditional way of life of tribals in areas they dominate. Telecom connectivity is poor in these areas, so people have suffered “bahut, bahut, bahut nuksaan” (huge losses) because of the app. When the pandemic was raging there was little NREGA work and people died of hunger, Tirkey says. Now NREGA work is available, but the app comes in the way of people getting their dues.

The NREGA Sangharsh Morcha platform, that brings together civil society groups engaged in Right to Work and Right to Food campaigns, has quite a few tweets about the disruption that the NMMS has caused.

“The app does not address a felt need,” says Sudha Narayanan of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Narayanan has tracked the evolution of NREGA through surveys and academic studies since it was rolled out nationally in April 2008. NREGA work is paid according to a schedule of piece rates on the basis of output measured by panchayat officials deputed for the purpose; people are not paid according to time worked. The job cards are a record of attendance; they show the hours worked, the amount of work done and the wages due. Narayanan wonders how photos in a central repository from 2.6 million worksites (currently) can help in monitoring the programme. “It is a solution in search of a problem,” she says.

In a statement in the Lok Sabha on March 14, the rural development ministry said it had modified the photo uploading requirement on the request of some state governments. The photos can be recorded offline and uploaded when connectivity is established. In exceptional circumstances, it said, the district programme coordinator can upload manual attendance. Narayanan says workers are uploading all kinds of photos, even those that show them at places other than the worksite, and even the same photo multiple times.

Invest in social audits

The NMMS is supposed to be “improving citizen oversight and increasing transparency in NREGA works”, but it’s hard to see how this is being achieved. Earlier, works were geo-tagged and there were ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures to assess the work done. “The Act provides for social audits by third parties as a monitoring and compliance mechanism. But the government does not release enough funds for social audits,” says Rajendran Narayanan, who teaches mathematics at Azim Premji University and is a founding member of LibTech India, an organisation that works on transparency and accountability in welfare schemes.

In a statement in the Lok Sabha, the rural development ministry said it had modified the photo uploading requirement on the request of some state governments

32nd Day of 100 days of Dharna at Jantar Mantar

Nirmala from Banaras, Uttar Pradesh

We are very poor, we work in every difficult condition without complain, our demands are very simple, we want to work and to be paid for our work. pic.twitter.com/MI8Hsw0g96— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) March 27, 2023

Surekha Ji from Chapuli village, Khanapur Taluka in Belgam District of Karnataka is here to protest against Digital interventions in the #MGNREGS. She informs that her village is situated in a forested region where network is extremely poor and their attendance are not marked. pic.twitter.com/UorrN1M9NX

— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) March 28, 2023

Gangaben has come all the way from Panchmahal district of Gujarat. She says, that she worked for eight weeks last year but not paid for two weeks and now she's not being given work anymore. On complaint to the panchayat, she got to know that her aadhar is not linked. (1/3) pic.twitter.com/HIObHcgKiI

— NREGA Sangharsh (@NREGA_Sangharsh) April 11, 2023

The flexibility that women had of working on NREGA sites and attending to household chores has eroded with the app-based attendance. Earlier, women workers would report to work early in the day, do the set tasks and return home. This encouraged women’s participation. The share of active NREGA women workers is 50.53%, which is more than the Act requires (a third) and higher than the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) of rural women—24.7% in 2019-20. LFPR is the proportion of rural women in the working age group who are either working or seeking work.

The other grievance that has drawn NREGA workers to the capital relates to the Aadhaar and bank account linking, which was made mandatory for receipt of wages from April 1. Aadhaar biometrics have made identity verification easy and transformed banking. But among NREGA workers they have some way to go. According to the NREGA dashboard, of the 150 million active workers, about 104 million or 69% are eligible for Aadhaar-based payment systems. Right to work activists say there are multiple issues with Aadhaar linkage. There are a sizeable number of workers who do not have the documentation for Aadhaar IDs. To meet bank KYC requirements, they have to make a couple of trips to bank branches, which is not easy when long distances have to be traversed on foot and bank computers are often down. Errors happen while linking Aadhaar with bank accounts. Though Aadhaar linkage is meant for convenience — workers don’t need to remember their bank account numbers — it’s often a deterrent, as these tweets show. Hence the NREGA Sangharsh Manch (NSM) suggestion that workers should also be given a choice of getting money transferred to accounts without Aadhaar linkage.

Constant underfunding of NREGA

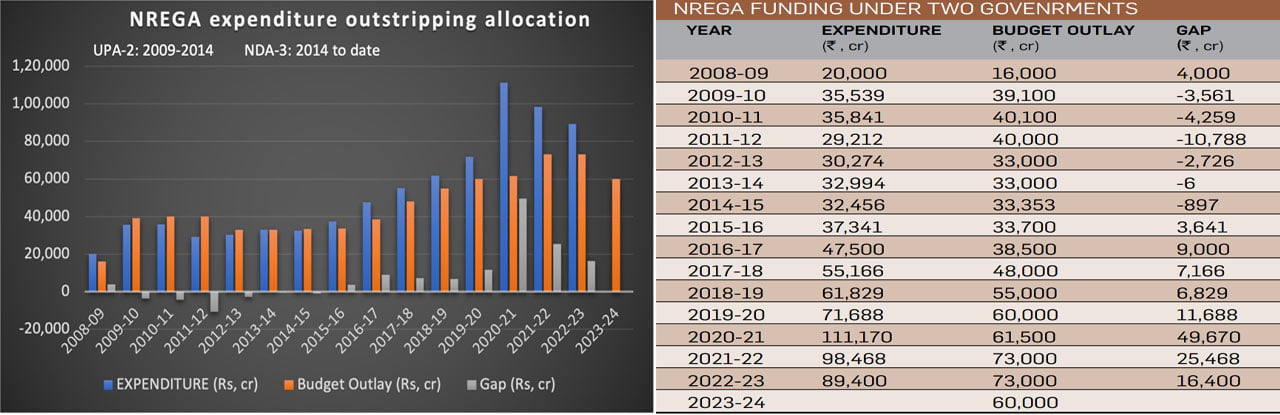

The third grievance being voiced at the protest site is the cut in NREGA budget allocation to ₹60,000 crore—61% of the amount spent on NREGA work last year. The finance minister says NREGA is demand-driven, so the outlay can be increased through supplementary demands later in the year. But this government has consistently underprovided for it (see table and graph). Last year’s budget estimate was ₹73,000 crore. It was revised to ₹89,400 crore at the end of the year. The actual expenditure is about ₹9,000 crore more, according to NSM. It will have to be met from this year’s reduced outlay. In 2021-22, the expenditure of ₹98,467 crore was 35% more than the budget estimate.

So the question that arises is, is the government trying to discourage NREGA workers? NREGA is a unique scheme in that it gives each rural household the right to demand 100 days of work a year. Work has to be given within 15 days of demand, failing which compensation has to be paid (seldom done).

In a 2017 study, Narayanan and three other researchers observed that implementation delays in NREGA works caused what they call the “discouraged worker effect”. Using data from National Sample Surveys of 2009-10 and 2010-11, they found that administrative rationing or the unavailability of NREGA work when sought, turned off workers from the scheme. A 10% rise in a district’s administrative rationing rate reduced the probability of a household seeking work by 3.4% to 3.5% percent. For poor households the discouragement effect was slightly higher at 3.8% to 3.9%. The district-level demand rate decreased by 8.9% to 9.2% in response to a 10% rise in the rationing rate. The rationing was caused by lack of administrative and technical capability at district and sub-district levels to create a shelf of works.

Asked whether producing the “discouraged worker effect” through the NMMS app was a policy objective, Narayanan said she could not read the government’s intentions but the app was a “disaster”. If payments become uncertain and there are strong chances of not being paid, people will not take the gamble of working in the first place. They can live with delayed payments, but not denied payments.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not warmed to NREGA. In October 2014, 28 economists wrote to him, expressing dismay at moves they felt would dilute or restrict the Act

Reluctance from the top for NREGA

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not warmed to NREGA. In October 2014, 28 economists wrote to him, expressing dismay at moves they felt would dilute or restrict the Act. In February the following year, he said he would let NREGA continue as a “living memorial” to the failure of Congress governments to provide gainful employment.

Government’s view: Technology is meant to help workers

The joint secretary in charge of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), Amit Kataria, said it was “laughable” when told that the implementation of the attendance marking software without extensive testing in the field, as well as the budgetary cut, had roused suspicion that demand restraint may be a policy goal.

He said NMMS, the attendance marking app, will expedite wage payment as on-site presence of workers is registered instantaneously. He admitted that it is not humanly possible to sift through the thousands of photographs that pour into the database every day. They serve as records for the moment, but software is being developed to match the photos with Aadhaar IDs. The app will not deny flexibility to women workers, as they can report for work early in the day and mark attendance in the first instance until 12 noon, and in the second instance after four hours.

Kataria said connectivity was an issue in 10% to 15% of the country. In any case, photos could be in queue in the smart phone and could get uploaded when network connectivity was established. He said the app would prevent ghost work and the deployment of earth-moving machines in place of manual work. Asked why he had not met the activists and workers of the NREGA Sangharsh Morcha, the group coordinating the protests, and stated his point of view, he said he had but the activists seem to be technology averse.

Kataria admitted that social audits had slowed because of the pandemic but this year the target was to audit all gram panchayats. Social audits are “top priority,” he said. On the West Bengal stalemate, he said there were irregularities which had been repeatedly pointed out but the state had not acted to correct them. Hence, a decision was taken to halt payment by invoking a section in the NREG Act in March last year. He said a final decision would be taken “very soon”.

Contrary to the PM’s claims, NREGA is a safety net. The wages are lower than the minimum wages. Hard manual work makes it self-selecting. The best days of NREGA were under the Manmohan Singh government. Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader Raghuvansh Prasad — who died in September 2020 from post-Covid complications a few days after resigning from the party — was enthusiastic about it as minister of rural development.

The scheme was continually tweaked to fulfil its objective of providing livelihood security through the creation of durable community assets

Proponents of the scheme like economist Jean Dreze and activists like Aruna Roy of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sanghatan were in the National Advisory Council headed by Congress chairperson Sonia Gandhi. People were perceived as rights holders and not just beneficiaries or supplicants. The scheme was continually tweaked to fulfil its objective of providing livelihood security through the creation of durable community assets. It was also envisaged as a programme to put a floor on rural wages and a channel for democratic assertion. A decentralised programme on such a vast scale would provide scope for corruption. This was sought to be reduced through third-party social audits, information walls (project details painted on the walls of panchayat offices, anganwadis and schools), and Right to Information disclosures.

Budget outlays under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh were always higher than the actual spend, except in the first year of national rollout. Currently, under-provisioning has become the norm. The difference between budget outlay and actual expenditure was the highest in 2020-21 at ₹49,670 crore — 80% of the budget outlay. In the next financial year, when the full impact of the pandemic was felt, the outlay fell short of expenditure by ₹25,468 crore.

The outlay of ₹60,000 crore this year seems to be on the lower side, given that the economy is expected to grow slower than last year because of global contraction

The outlay of ₹60,000 crore this year seems to be on the lower side, given that the economy is expected to grow slower than last year because of global contraction. Rainfall is also expected to be deficient. Officially, the monsoon is forecast to be ‘normal’ with total precipitation at 96% of the Long Period Average — that is, at the lower end of the reference range. But there are chances of rainfall being less than normal because of the increasing probability of El Nino, a warm water phenomenon in the east-central equatorial Pacific linked to drought in India. If that happens, there will be more rural distress and more demand for NREGA work.

Not a make-work programme

Critics of NREGA among economists and policymakers see it as a make-work programme where people busy themselves digging holes and filling them up. But Narayanan says it has created durable assets of use to the community and for agricultural resilience like farm ponds to store rainwater and recharge aquifers, bunds to check flooding and seawater ingress, trenches along slopes to prevent soil erosion and conserve rainwater, and dirt tracks to connect remote farms with main roads. NREGA wages have also been used for mangrove restoration, construction of bamboo greenhouses and to level the fields of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe farmers for more productive agriculture.

Critics of NREGA among economists and policymakers see it as a make-work programme where people busy themselves digging holes and filling them up

But corruption cannot be dissociated from NREGA. In 2015, I visited Agra and Mathura as a TV news reporter to check whether crop insurance had helped farmers recoup losses to the wheat crop caused by a fierce hailstorm. When an elderly farmer showed me his bank passbook so I could verify that he had paid the insurance premium, I found payments for NREGA work he had not done. Later, I came across another instance of corruption in NREGA in a Dalit basti in Bihar.

“Even the greatest fan of NREGA will admit that there is a lot of scope for corruption,” Narayanan says. But it is not on a scale that undermines it. In 2014, she says, she did an evaluation of NREGA assets in sample districts across Maharashtra for the state government as a researcher at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research. Eighty percent of the 4,600 works existed and they were good assets. Of the remaining, 12% were protective structures like sand banks that had collapsed but could be inferred from the ruins, while 8% were ghost works.

Of late, NREGA is being used to advance government schemes like construction of toilets or low-cost housing. The 60:40 ratio of wages to material is getting skewed towards more expenditure on material. The new works also have lower employment potential. And they provide scope for contractors to collude with officials.

But never before have allegations of corruption been used to deny funds to a state. In a first, the Centre has not paid NREGA workers in West Bengal since the last week of December 2021. The state has a 10th of NREGA’s active workers. The ruling parties at the Centre and the state see themselves as adversaries. The workers have been caught in the crossfire for more than a year.

Of late, NREGA is being used to advance government schemes like construction of toilets or low-cost housing. The 60:40 ratio of wages to material is getting skewed towards more expenditure

NREGA is not being implemented strictly according to the Act. For all its shortcomings, it provides a lifeline. In 2020-21 and 2021-22, when the country was wracked by waves of the pandemic, NREGA — and huge buffer stocks of food grains — saved people from hunger. That crisis showed that cancellation of job cards after three years of non-use was a mistake. Returning migrants whose job cards had been cancelled had to go through the process of re-enrolling — and lost wages they were in dire need of. Interventions like these, which are not thought through, cause real harm. Narayanan says some of the technological innovations address the anxieties of administrators, without improving the efficacy of the scheme. They also help clever people without scruples to game the system.

The irony of the two groups of government employees protesting at the Jantar Mantar site was not lost on the NREGA protesters. “6 mahine aaram, 6 mahine kaam. Phir bhi pao poora daam aur bonus alag se” (Six months work, six months off, but full pay and bonus too) taunted their banner in a reference to the number of days that public officials can gainfully take off from work. But when NREGA enrolees demand work, not paid leave, the government breaks into a sweat.