India is no stranger to railways being carried up steep hilly slopes with three such 19th-century rail projects finding a place on the UNESCO World Heritage List. When steam locomotion was combined with rails in the first third of the 19th century by Robert Stephenson, it aroused the world’s awe and wonder and India was no different. In those days of empire building and the industrial revolution, the railways were viewed as the key to prosperity and development. The imperial types emphasised the role of railway engineers as harbingers of ‘civilisation’. So dominant were the technology and development narratives that the social and environmental issues were ignored.

The technological ‘triumph’ of the worldwide spread of railway networks also led to an unprecedented exploitation of human and other resources. “The initial cost in human life and misery were all too often appallingly high,” according to British Museum curator and historian Anthony Coulls. He wrote this in his introduction to a paper on heritage railways written for the World Heritage Convention organised by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Though there has been a steady decline in railway networks across the world, in India they are still held out as showpieces of technology and development as new railroads are being built in unstable hilly regions to bring prosperity and development to areas that were hitherto not part of the network.

The environment, however, is often forgotten in the haste to obtain such dubious distinctions as the world’s highest railway bridge or the longest tunnel. The devastating landslide in Manipur in June-end in which more than a hundred people lost their lives is emblematic of the disregard for both the environmental and human consequences of such a path. The pattern has become all too familiar—disasters strike regularly, occupy the media centre-stage for a few days, inquiries are ordered and then things continue as before until the next big one.

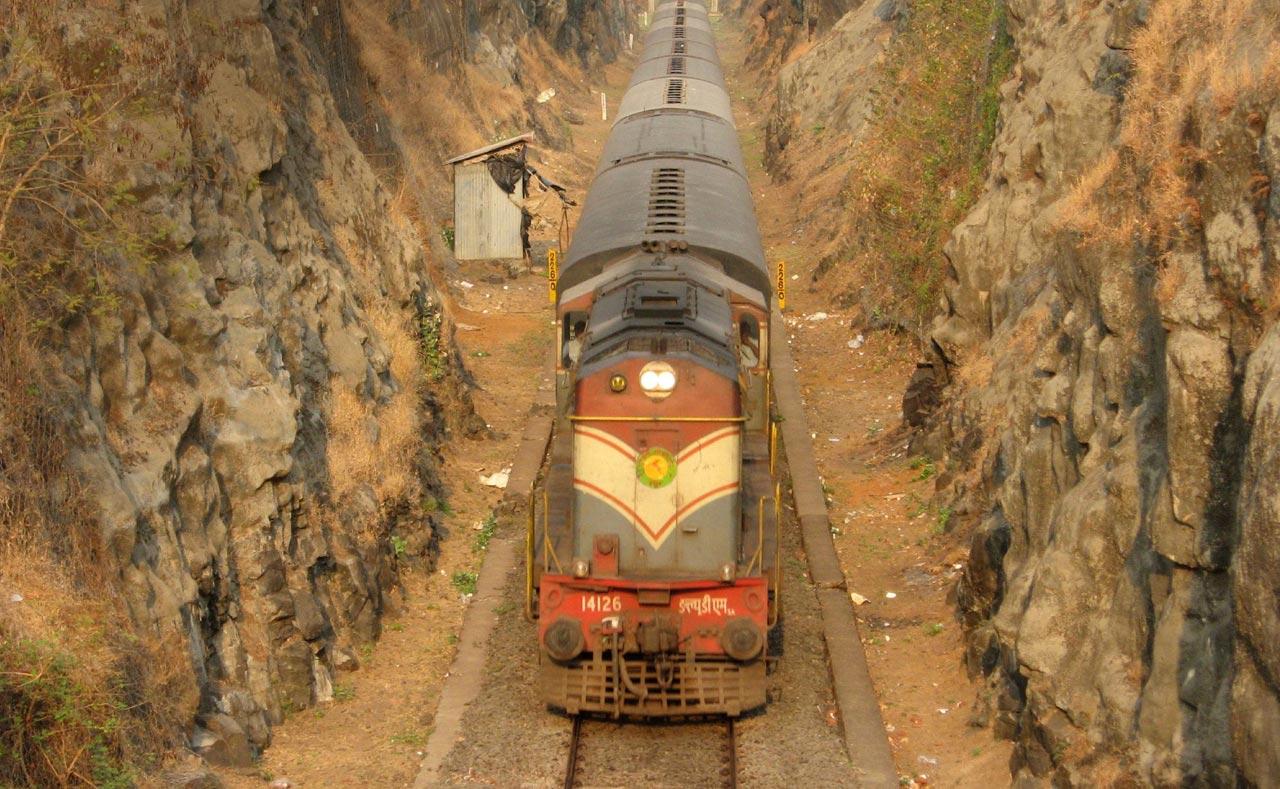

Currently, three major projects are underway in the ecologically sensitive Himalaya—one in Kashmir, another in Uttarakhand and the third in the Northeast. They are, of course, following in the trail of the much-acclaimed Konkan Railway built along the Western Ghats. Unlike the early railroads in the hills laid out by the British rulers in their enthusiasm, which were narrow gauge, the ones that have been built or are being planned post-Independence are broad gauge. Construction of broad gauge is quite a different kettle of fish in unstable mountainous regions.

The first railroads in hilly regions in India by the British were the Darjeeling Hill Railway, the Kalka-Simla Railway and the Neelgiri Railway. The first two were built out of multiple motives of strategy, commerce and as affordable means of transport for those British employees and their families who wanted to escape to the cooler environs of the Himalaya during Indian summers that they found oppressive. The projects were also looked upon as challenges of nature that were to be overcome by the superior engineering talents of Englishmen. Incidentally, all of them coincided with the expansion of the British Empire in India.

The Darjeeling Hill Railway was the first hill railway built by the British, partly for strategic reasons to back their expansion in India and partly to enable travel to a summer resort by their officials and civilians. Acquired by the British from Sikkim in 1833, Darjeeling became contiguous with the Bengal Presidency by 1850. After slow initial growth, Darjeeling’s fortunes began to look up after the start of tea plantations. The only drawback was the lack of transport. Both the major railways that operated in the area—the Eastern Bengal Railway (EBR) and the Northern Bengal Railway (NBR)—hesitated to provide a rail connection to Darjeeling.

Though there has been a steady decline in railway networks across the world, in India they are still held out as showpieces of technology

Finally, an agent of the EBR, Franklin Prestage, prepared a scheme to build a narrow gauge (two feet or 600 mm gauge) rail connection between Siliguri in the plains and Darjeeling at 2,000 metres. The highest point was Ghoom at 7,402 feet (2,256 m). Started in 1879, the project was completed within two years using some unique innovations that allowed the rail line to reach the higher elevations without excavating tunnels. The steep climb was achieved through zigzags and loops to save expenditure. The project was completed within two years and hailed as a feat of civil engineering, much as many Indians these days view the building of tunnels and bridges in the Himalayan rail projects.

Encouraged by the success of the Darjeeling rail project, the British undertook to build another line—this time connecting Simla and Kalka in the foothills of northern India that in turn was the terminus of a broad gauge line from Calcutta (then the capital of British India). Simla (now Shimla) had become by that time the summer capital of the British government in India. The project started in 1898 and was completed in 1903, but this time on a wider two feet and six inches (760 mm) or narrow gauge line. But, unlike the Darjeeling project, this one included more than a hundred tunnels and several hundred bridges and viaducts.

Though the Darjeeling rail was hailed as an engineering feat, it was not free from troubles. In the cyclone of 1899, says an EBR handbook, From the Hooghly to the Himalayas, long stretches of the railway were completely destroyed. The same handbook, published in 1913, mentions that the line always faced the hazard of being breached by “torrents and land slips”.

Though these three essentially light railways have survived the vagaries of time, even making it to the UNESCO list, not all hill railways did. For instance, the Cherra-Companigunj State Railways that was built in 1886 to connect the coal mining areas in the hilly regions of the Khasi and Jaintia hills (now Meghalaya) with Companigunj in Sylhet district (now in Bangladesh) had to be shut down after a major portion of the tracks was destroyed in the earthquake of 1897.

Fast forwarding to more recent times, the first railway project in an ecologically sensitive zone was the Konkan Railway Project whose construction started 32 years ago. Unlike the previous efforts by the British, this one was an ambitious broad-gauge railway running along the Western Ghats or the Sahyadris through three states—Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka. It was in 1998 that the first train rolled on this much acclaimed 740-km project. But within a few years the drawbacks of such projects started to become clear. In June 2003, the first accident occurred when a holiday special on its way from Karwar to Mumbai collided at night with a rock and debris loosened by a landslide that had blocked the entrance of the Nerle tunnel. The impact was so severe that the locomotive and three coaches jumped the tracks, resulting in the deaths of 51 people.

The Nerle tunnel was among the 92 that were part of the Konkan Rail Project that had as many as 2,000 river bridges built over gorges. Newspaper reports had headlined the accident as ‘rare’ since it was the first after the rail line was opened to traffic. Railway authorities blamed it on the unusually heavy rains that had lashed the area. No mention was made of the generally fragile nature of the landscape through which the railroad had been built. As time passed, the ‘rare’ accident became more commonplace; exactly a year later, in June 2004 the Matsyagandha Express travelling from Mangaluru to Mumbai was pushed off the tracks by a landslide. The locomotive fell off the viaduct into a riverbed with two coaches nearly following it. The accident claimed 14 lives while more than 60 people were injured.

Accidents on the Konkan Railway have occurred at regular intervals—19 people were killed and 132 injured in May 2014 when the locomotive and four coaches of a passenger train between Diwa and Sawantwadi in Raigad district of Maharashtra were derailed. All that B. Rajaram, the then managing director of Konkan Railway, had to say was that the “best foolproof” safety measures did not work against nature’s fury. The latest accident was when a landslide in Goa smashed into a train travelling from Mangaluru to Mumbai during the monsoon last year, though no lives were lost. This year too, in early August train services on the Konkan Railway were disrupted due to a landslide between Murdeshwar and Bhatkal in the Karnataka section.

In June 2003, the first Konkan Railway accident occurred when a holiday special collided at night with a rock loosened by a landslide

Kalis Goppers, development expert from the Swedish International Development Association (SIDA) that assisted in building the line particularly with regard to tunnelling, admitted to the great difficulty posed by the terrain. Soft soil tunnels where water gushed in and mud caved in and collapsing embankments were some of the major problems faced during construction, according to Goppers. In addition, the area is also earthquake-prone with a hundred quakes having occurred in the past 400 years, the most serious being the Koynanagar quake of 1967.

The weakest points in all these quake-prone mountain railways are tunnels as is evident from the experience of the Konkan Railway

But notwithstanding the experience of the Konkan Railway, the ambitious and very popular Char Dham Rail Project for Uttarakhand has been put on the fast track without any consideration for the calamities that have been striking the Himalayan state, beginning with the Kedarnath floods of 2013. Just last year flood waters destroyed the tunnel-based Tapovan-Vishnugad dam in whose vicinity the rail line connecting Rishikesh with Karnaprayag (125 km) will pass. Despite this disaster in which more than a hundred people lost their lives, the rail project is going full steam ahead. This section of the project alone will have as many as 17 tunnels, the longest being of 15 km at Devaprayag.

A third major rail project is underway in unstable mountainous region in Jammu and Kashmir to connect the Jammu region with the Kashmir Valley. More than half the 272-km project was completed a decade ago—from Udhampur to Katra and from Banihal to Baramulla—a total of 160 km. Trains are being run on it. The most difficult part—a 111-km stretch between Katra and Banihal—is understandably taking the longest time since nearly all of it will pass through tunnels (27 in number). The most talked-about part of this section is the 1.3-km Chenab suspension bridge which at 359 metres will be the world’s highest railway bridge.

The weakest points in all these unstable and quake-prone mountain railways are tunnels as is evident from the experience of the Konkan Railway. The major difference, as mentioned earlier, is that the new projects are all broad gauge. According to railway experts, a tunnel has to be at least three times the width of the gauge to accommodate carriage clearance. This in turn means that the tunnel widths have to be at least three times more for broad gauge compared to narrow gauge. That width is roughly five metres. The wider the tunnel dug in unstable rock and soil conditions, the greater the risk of landslips and rockfall as has been witnessed throughout the 25 years that the Konkan Railway has been in operation.

So, while Indian egos may be boosted by the longest tunnels, highest bridges and engineering marvels, the danger that such ego-boosters pose for the environment and the lives of the people are usually ignored since the effects come about only after a lapse of time.