The year-long farmers’ agitation against the central government’s three farm laws has, to some extent, drawn the country’s attention towards the plight of tillers and the existing lacunae in the agriculture sector. Protests and demonstrations have taken place earlier too, but this was the longest one ever. The general indifference towards tillers and agriculture is ironic, considering that about half of India’s population is engaged in agriculture.

According to World Bank data, employment in agriculture was about 43% in 2019. This was significantly higher than employment in agriculture across the world, which was about 27%. At the height of the lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic, the agriculture sector was the saviour of the country’s economy.

According to National Sample Survey Report No. 587: Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Livestock Holdings of Households in Rural India, 2019, the average monthly income per agricultural household in 2018-19 was ₹10,218. Out of this, income from wages was ₹4,063, income from leasing out of land ₹134, net receipt from crop production ₹3,798, net receipt from farm animals ₹1,582, and net receipt from non-farm business ₹641. Thus, out of their total income, agricultural households earn 39.8% from wages followed by 15.5% from cultivation, and animal husbandry, and about 6.3% from non-farm businesses. The survey revealed a 59% surge in farmers’ incomes. The figures are not adjusted for inflation.

According to World Bank data, employment in agriculture was about 43% in 2019. This was higher than employment in agriculture across the world, which was about 27%

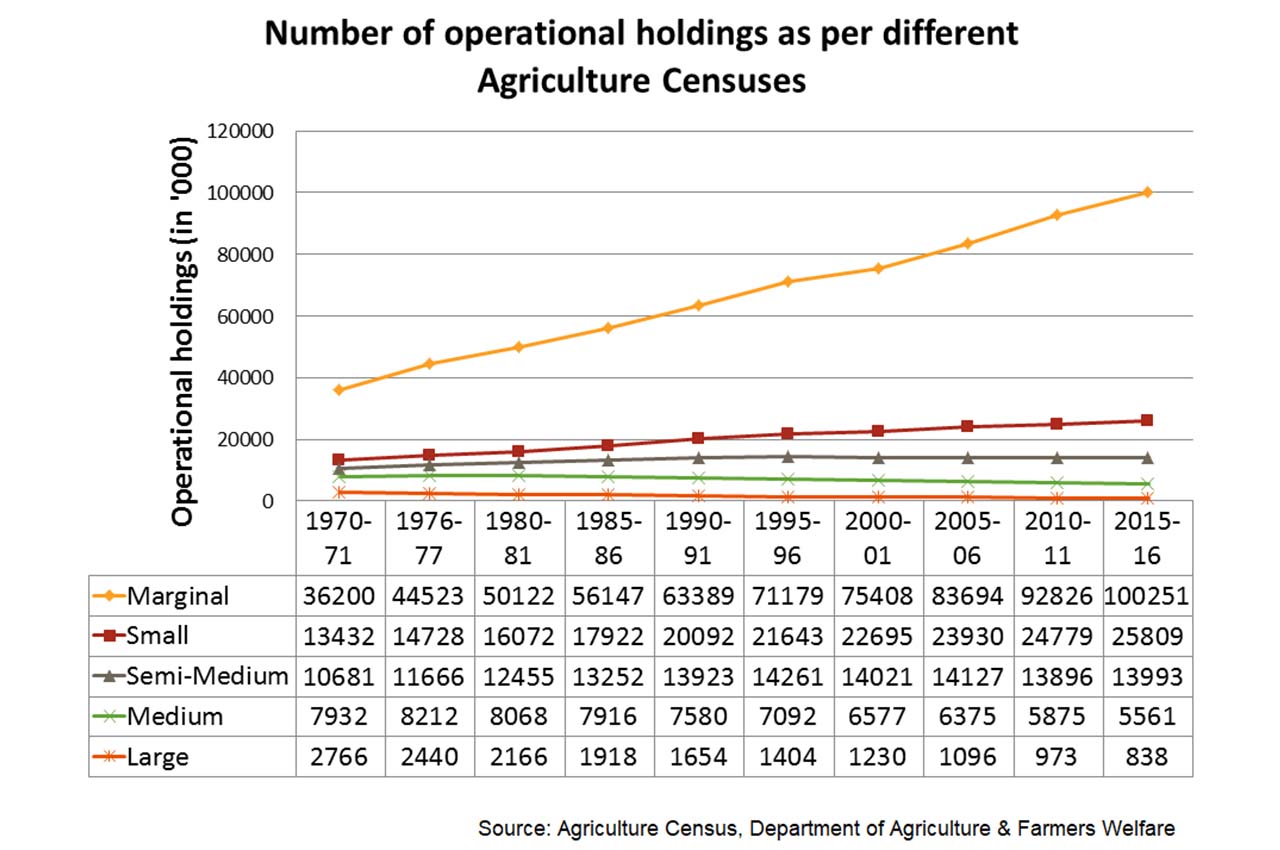

Owners with large and medium land holdings hire labour for agriculture. Though they comprise 5% by size group, as per the Agricultural Census of 2015-16, their landholding amounts to about 30% of the total. According to this data, 86% of farmers in India are with marginal or smallholdings with less than two hectares (or five acres) of land. Altogether, this group holds about 47% of agricultural land. The rest are with semi-medium landholdings.

Contrary to the popular narratives in the media, the majority of large landholders did not participate in the protests against the farm laws. The protests at Delhi’s borders that began on November 26, 2020, were against the Acts passed by Parliament in September. The contentious laws have since been revoked by the lawmakers and the umbrella organisation of the protesting unions— the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM) —has “temporarily” suspended its agitation. However, the forum of some 400 farmers’ organisations is still waving its charter of demands at the government. The union leaders complain that though the government has agreed to constitute a committee to address their demands, such as legalising the Minimum Support Price (MSP), it is yet to announce its formation.

Farmers’ lives matter

As per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) statistics, 10,677 persons involved in the farming sector died by suicide in 2020, accounting for 7% of the total of 1,53,052 suicides. Among peasants who died by suicide, 5,579 were farmers and 5,098 were agricultural labourers. A majority of the suicides in the farming sector were reported from Maharashtra (37.5%), Karnataka (18.9%), Andhra Pradesh (8.3%), Madhya Pradesh (6.9%) and Chhattisgarh (5.0%).

For India, availability of potash, which is a key component in manufacturing fertilisers, is under threat. Russia, Ukraine and Belarus together made for about 12% of India’s total fertiliser imports

“Input prices are all skyrocketing—diesel, petrol, pesticide, fertilisers are all at a high. The dole of ₹6,000 handed out per year (in three equal instalments under the PM Kisan Yojna) hardly makes a difference,” complained 67-year-old Randhir Singh Kungar, a farmer from Charkhi Dadri in Haryana.

Now, Russia’s attack on Ukraine is adding to concerns that global food inflation will grow. Russia has asked its fertiliser manufacturers to reduce exports as the war rages, leading many governments to fear a stock shortage. The price of natural gas is also escalating, which is the main input for most nitrogen fertilisers. For India, the availability of potash, which is a key component in manufacturing fertilisers, is under threat. Russia, Ukraine and Belarus together made for about 12% of India’s total fertiliser imports. India was also the largest market for Ukraine’s sunflower oil.

Last year, China’s active domestic season and reduced exports impacted supplies to the Indian subcontinent with global players seeking higher Di-Ammonium Phosphate (DAP) prices prevalent in the Europe and US markets. In May 2021, the subsidy for DAP was increased from ₹500 to ₹1,200 per bag. The Centre spends about ₹80,000 crore on subsidies for chemical fertilisers every year. With the increase, there was an additional spend of ₹14,775 crore as subsidy in the last Kharif season.

Seeking legislation according to MSP legal sanctity, Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) leader Rakesh Tikait, who evolved as the poster boy of the farmers’ protests, reiterated: “We have not called off our struggle. We have announced a pause. There are a number of issues which are yet to be resolved.” The unions want the government to enact legislation conferring mandatory status on MSP, rather than it being just an indicative or desired price. The Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) — a peasant organisation that is politically linked to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — also seeks the legalisation of MSP. However, it did not take part in the protests.

The mandate to recommend MSPs rests with the Commission for Agricultural Costs & Prices (CACP), which is attached to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare. It comprises a chairman, member secretary, a member (official) and two members (non-official). The non-official members are representatives of the farming community and usually have an active association with it. The CACP recommends MSPs of 23 commodities, which comprise seven cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, sorghum, pearl millet, barley and ragi), five pulses (gram, tur, moong, urad, lentil), seven oilseeds (groundnut, rapeseed-mustard, soybean, sesame, sunflower, safflower, nigerseed), and four commercial crops (copra, sugarcane, cotton and jute).

While the hunt for suitable candidates is going on since November 2020, ‘members who have an active association with the farming community’ are included as and when required

The posts of the two non-official members who are supposed to be representatives of the farming community have been vacant for more than a year. While the hunt for suitable candidates is going on since November 2020, ‘members who have an active association with the farming community’ are included when required in official meetings.

Devoid of reality

Instead of first-hand, field-based pricing studies, CACP projections are made using state-wise, crop-specific production cost estimates provided by the Directorate of Economics & Statistics in the agriculture ministry. The CACP also projects three kinds of production costs. A2 covers all paid-out costs directly incurred by the farmer (whether in cash or kind) on seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, hired labour, leased-in land, fuel, irrigation, etc. A2+FL adds an imputed value of unpaid family labour. C2 is a more comprehensive cost that factors in rentals and interest forgone on owned land and fixed capital assets, on top of A2+FL. “CACP recommendations are much below the costs incurred by a farmer,” claimed Hannan Mollah, general secretary of the Left-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS). “The Commission’s suggestion takes into account the only the price of the raw material and family labour,” he added. The Odisha government had also asked the Centre to increase the MSP of paddy to ₹2,930 per quintal for its farmers. The state has pointed out that peasants have also been facing the vagaries of nature.

“In the case of paddy, for every quintal procured, the Centre is paying farmers ₹630 less than what the Swaminathan Committee proposed,” says Abhimanyu Kohar of the Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh (RKM) — an association of more than 60 farmer bodies. Kohar was referring to a report by the National Commission on Farmers (NCF), which was constituted in 2004 under the chairmanship of the noted agriculture scientist, Dr M.S. Swaminathan. It’s popularly known as the Swaminathan Commission.

The Commission submitted five reports, the last on October 4, 2006. Farmer unions demand the implementation of the Commission’s formula for C2+50%. This means ensuring 50% on returns, taking into account all costs of cultivation, including the imputed cost of capital and the rent or lease on the land (even if owned). “For cotton, the C2+50% formula works out to ₹7,753 a quintal but the government announced an MSP of ₹5,726 per quintal. Thus, here too, farmers are losing out ₹2,027 on each quintal,” adds Kohar. According to Badrinarayan Chaudhary, general secretary of BKS, “For a farmer, MSP is the primary issue. All farmers do not benefit from government procurement, it’s a minuscule proportion.” He too maintained that the Centre should legalise MSP, even if it is not C2+50%. This, he assumes, would ensure support price to farmers even if their product is procured by private players. But SKM leaders maintain that farmers can avoid falling into debt only if the government guarantees payment as per the C2+50% formula.

Farmer unions demand the implementation of the Commission’s formula for C2+50%, ensuring 50% on returns, taking into account all cost of cultivation, including the cost of capital

Ensuring the right price

There is a difference in opinion over the pricing of produce. “Only 10% of the farmers have access to Mandis. Most farmers are forced to sell their produce elsewhere,” says Mollah. “In the case of paddy, the CACP has recommended an MSP of ₹1,940 per quintal while the grower spends ₹2,200. And the same produce, if sold outside a mandi, may fetch him something as little as between ₹11,00 to ₹12,00 per quintal.” Incidentally, Kerala offers ₹2,800 per quintal of paddy. In June last year, the government raised the MSP for paddy by ₹72 per quintal for 2021-22. Rates of other Kharif crops were also hiked following a decision taken by the Cabinet headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. But Punjab’s Shiromani Akali Dal president, Sukhbir Singh Badal, who walked out of the NDA over the now-repealed farm laws, had termed the hike “meagre”.

Kavitha Kuruganti, a social activist involved in empowering farmers and sustainable farm livelihoods, agrees with Mollah, pointing out that farmers are getting lower income than mandated. Even Dinesh Dattatraya Kulkarni, organising secretary of the RSS-affiliated BKS, agrees that barely 10% of the country’s farmers can avail of MSP.

“MSP is currently the main issue before farmers. All farmers are not benefiting from government procurement. Only about 8-10% of farmers benefit,” claimed Kulkarni. “To reduce the cost of production of farm produce, the government should think about the DBT (direct bank transfer) scheme for agriculture inputs, fertiliser, seed, electricity etc. by abolishing all subsidies given to the agriculture sector and by providing a minimum of ₹12,000 per acre per year.”

The number of farmers benefiting from MSP is difficult to assess accurately. In a written answer tabled in the Lok Sabha on August 3, 2021, the minister for agriculture and farmers’ welfare, Narendra Singh Tomar, explained, “The procurement at Minimum Support Price (MSP) is being done by Central and State Agencies under various schemes of the government. Besides, the overall market also responds to the declaration of MSP and government’s procurement operations which results in private procurement on or above the MSP for various notified crops.” Thus, it is difficult to reach an exact figure.

In June last year, the government raised the MSP for paddy by ₹72 per quintal for 2021-22. Rates of other kharif crops were also hiked following a decision taken by the Cabinet, headed by the PM

The minister added: “Government of India announces Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for 22 major agricultural commodities of Fair Average Quality (FAQ) each year in both the crop seasons after taking into account the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). The government also extends remunerative price to farmers through its various interventions schemes.”

The procurement centres, Tomar said, are opened by respective state government agencies and central nodal agencies like NAFED, FCI and so on “after taking into account the production, marketable surplus, convenience of farmers and availability of other logistics, infrastructure such as storage and transportation etc. A large number of the purchase centres in addition to the existing mandis and depots/godowns are also established at key points for the convenience of farmers to ensure procurement at MSP”.

The government, however, mentioned that the number of farmers who benefited by selling in the mandis in 2018-19 was 1,71,50,873, which increased to 2,04,63,590 in 2019-20 and reached 2,10,07,563 in 2020-21. Considering that close to half of India’s population is employed in agriculture, that is indeed a small number.

“The APMC (Agricultural Produce Market Committee) Act was done away within 2006 itself in Bihar. A loud clamour was raised even at that time in the state legislative assembly as well as the legislative council. It all died down. Since then mandis have not existed in Bihar and farmers are free to sell their produce anywhere they want,” claimed Bihar’s ruling Janata Dal (United) leader Rajiv Ranjan. “You will be happy to know that farmers in Bihar do not commit suicide, they do not die of starvation. We offer input subsidy to farmers.”

However, Upinder Kumar Sharma, a farmer from Vaishali district in Bihar, who is also the secretary of a local farmer union, told the news website The Wire that the major problem for farmers in his state is the lack of market opportunities. Despite the Centre’s announcement of MSP, farmers like him are forced to sell to middlemen or agents at rates much below the government stipulated one because government purchase is minimal and there is no check on state agencies when it comes to purchases. The APMC Act is in place in Punjab, Haryana, parts of Uttar Pradesh and to some extent in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where farmers can sell their produce in a mandi at MSP. Farmers from other states often take crops like paddy and wheat to Punjab during procurement season. However, the state government has stepped up vigil to ensure action against illegal transportation of produce from other states. This has led to a situation where peasants from other states are forced to sell their produce cheaply at the border and suffer huge losses while the buyer rakes in the profits.

The APMC Act is in place in Punjab, Haryana, parts of Uttar Pradesh and to some extent in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where farmers can sell their produce in a mandi at MSP

In western Uttar Pradesh, where sugarcane is grown in abundance, sugar mills are reportedly yet to pay farmers for their produce. “About ₹3,445 crore is pending since (crop year) 2019-20,” says Mollah. The Centre has fixed the minimum price that mills have to pay to sugarcane growers at ₹290 per quintal for 2021-22. Thus, the Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) of sugarcane was hiked by ₹5 per quintal from ₹285 for 2020-21. Although the government has initiated several measures for the benefit of tillers, they are mostly dismissed as too little. The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM Kisan Yojna) scheme ensures the direct transfer of ₹6,000 every year to farmers in three equal instalments. “PM Kisan Yojna has always been a cover-up, a feeble one at that, for this government’s failure to address farmers’ real issues,” complained Kuruganti. “The amount should have been at least ₹18,000 per year if it is meant to benefit the farmers,” adds Mollah.

CSR SPENDING COULD BE A WAY OUT

The provision of mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) expenditure on the agriculture sector may be helpful in bringing the farm sector out of distress, writes Delhi University professor Rajeev Kumar Upadhyay in his research paper, “Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Growth in Agriculture in India”.

According to this paper, CSR spending in agriculture is far less in comparison to many sectors such as education, healthcare, art and culture, and so on. Also, a few large firms were voluntarily spending a part of their earnings on CSR initiatives even before the provision relating to CSR was introduced in the Companies Act, 2013. The paper argues that there is a need to put in a mechanism to avoid the overlap of different government schemes and CSR projects.

Upadhyay adds that pooling CSR resources can help build and operate large projects to tackle problems of bottlenecks like cold storage and logistic infrastructure in agriculture. “Tax benefits to donations to entities involved in operating such agriculture projects will not only help to build such projects but increase economic activities in the rural economy,” the study suggests.

The research was aimed at finding out the spending patterns of CSR corpuses, using publicly available expenditure data on agriculture by 20 Indian corporates. CSR activities in agriculture, says the paper, cover a wide range of issues such as rainwater harvesting, the introduction of solar pumps, organic farming, seed management, soil management, delivery of agro information and marketplace ecosystem, etc.

Gender bias

The sector is particularly unfair to women farmers. Women’s contribution to farming is no less than men’s —in fact, they labour more with shouldering household chores and raising children in addition to working in the fields. But this is seldom recognised, and they hardly get the benefit of schemes, point out activists. According to the Mahila Kisan Adhikar Manch, which is working on such discrepancies, women farmers attend to 75% of agriculture-related work yet own only 12% of farmland. The Left-leaning All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) has been demanding that women farmers should also be recognised as farmers, “but the government is not ready to accept this,” it alleges. AIDWA claims that some 7.2 crore women have lost their jobs in agriculture and allied sectors in the past five years and more than four lakh male farmers have committed suicide since the onset of the agrarian distress. Their widows are yet to receive any debt waiver or rehabilitation package.

Many activists laud the efforts of Sharad Joshi in empowering women farmers. He founded the farmer organisation, the Shetkari Sanghatana, as well as the largest organisation of rural women

The Ministry of Women and Child Development, in its draft National Policy for Women 2016, articulating a “Vision for Empowerment of Women”, stated: “Wives of farmers who committed suicide on account of the failure of crops or heavy indebtedness are highly vulnerable and are left behind to take care of their children and family. Special package for these women that contains comprehensive inputs of programmes of various departments/ministries like agriculture, rural development, KVIC, MWCD will be provided for alternative livelihood options.”

The Centre, under the Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP)—a subcomponent of the National Livelihood Rural Mission (NRLM)—tries to improve the status of women in agriculture. According to the MKSP website, women farmers from Maharashtra have been the biggest beneficiaries with over 14 lakh availing of the scheme. Andhra Pradesh had the second-highest beneficiaries (almost 14 lakh) followed by Madhya Pradesh (close to 11 lakh). It adds that over 88 lakh women farmers have benefited across 1.4 lakh villages.

Many activists laud the efforts of Sharad Joshi in empowering women farmers. He founded the farmer organisation, the Shetkari Sanghatana, as well as the largest organisation of rural women, Shetkari Mahila Aghadi. It is celebrated for its work on women’s property rights, especially the ‘Lakshmi Mukti’ programme that has conferred land titles on lakhs of rural housewives. “Despite being pro-corporatisation and pro-liberalisation, he is probably the only farmer leader in India—that too a man—to have actually done a campaign to get his male members to part with parcels of land in the name of their women … their spouses,” says Kuruganti.

Small and marginal farmers and daily wage farmworkers are a lot that has been neglected, even taken for granted, say union leaders. They work under the open expanse of the sky; they take on the vagaries of nature; they stare at a bleak future where even daily bread is uncertain. Yet, they remain the most neglected of the lot.