It’s not business as usual at the Paona international market, popularly known as Moreh Bazaar, in Manipur’s capital city of Imphal. The absence of traffic jams is a dead giveaway of the lack of business. Even as the pandemic eases, and daily bustle is picking up, many shops along both sides of the Moreh Bazaar street remain shut.

Moreh Bazaar gained fame for selling goods that came in from neighbouring Myanmar. This once bustling market sold everything—clothes, shoes, watches, sports goods, toys, agricultural implements, electronic gadgets, among many other things. When times were good, the bazaar dominated a kilometre-long stretch and was one of the most popular and busy commercial markets in the state. It got its name for selling goods that came into Manipur through the border town of Moreh, including a lot of Chinese products.

Today, traders and shop owners are concerned about the lack of business. Deven, who owns a shop in the bazaar, says very few goods now come through the border even though markets are slowly opening up post Covid-19 restrictions. “The prices have gone up quite a lot,” says Deven, “so we cannot afford to make bulk purchases as earlier.” He says that a dress which used to cost ₹250 now costs ₹400. “Since prices are high, we don’t take more than five pieces of each item. Moreover, we cannot take risks because there are no customers,” he says.

At the moment, traders and retailers are relying on a few suppliers. “There is no point in going to the border since the Moreh Gate has been closed and with the price of petrol going up, travelling to the border has become expensive,” says Deven. “There is no profit. We are just about managing.” For small businesses and shop owners, giving up the trade is not an option because this is all they have done all their lives. Unlike Deven, who owns his shop, many others have to pay rent for the premises even when the business is lean. There are also those who have taken a bank loan.

Romila trades in clothes while her husband sells electronic items and kitchenware. “The market is dead,” she says, “we are struggling to keep it alive.” During the lockdown, Romila took all her merchandise to sell from her home in West Imphal. “I used to display the clothes in front of my house or sell it door-to-door whenever the lockdown eased for a few hours,” she recalls. Meanwhile, her husband would volunteer at the Covid-19 community care centre. “He supplied items like thermos flasks, water heaters, hot-water bags, and so on to keep the business going. Since people could not go out, he undertook delivery of the items to the caregivers.” Some, like Surbala, who survived by selling fish, are back in the market, but continue to struggle because there are hardly any customers.

Trade between India and Myanmar has existed since time immemorial. Even before the Indian economy opened up in the early 1990s and formal trading channels were established, Moreh Bazaar was famous for selling smuggled Chinese goods that came into India through the Myanmar border. The goods ranged from Chinese pens to light machinery and everything in between. But after the border trade agreement between the two countries was signed in 1994, and implemented the next year, business started thriving. According to the original agreement, border trade was supposed to take place through customs posts at Zowkhathar in Mizoram and Moreh in Manipur on the Indian side, while the towns of Tamu and Rhi were identified in Myanmar. But the bulk of goods flowed through the Moreh post on the Indian side. Officially, 40 items were allowed for cross-border trade at 5% duty, but unofficially hundreds of items were bought and sold on either side of the border.

Now, for more than two years, the border trade has remained suspended—first, due to the pandemic and then due to the political crisis in Myanmar since February last year when the military junta carried out a coup against the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi. Since then, the border gate at Moreh has remained closed.

With the closure of the border trade, it’s not just the shop owners and suppliers who have taken a hit. Local taxi and hotel owners and transporters are also affected by the downturn in commerce. A row of taxis can be seen awaiting passengers at Imphal’s Moreh taxi stand on the India-Myanmar road or Asian Highway-1 (AH-1). Unlike the past, even as normal life resumes, taxi drivers cannot get full occupancy. “Daily service is out of the question,” says Dinesh, who plies between Imphal and Moreh, “business has not picked up.” His friend, Akbar, joins the lament, “During the lockdown the taxis were issued a permit that allows us to ply. Now, most of my passengers are paramilitary personnel who are going on or returning from leave. Due to the closure of Moreh Gate, there are no tourists.”

Transporters like Dinesh, who have been in the business for more than 10 years, are finding it tough to deal with the downturn. “There is very little business left now. At best, I transport essential items like rice, vegetable, dal and so on from Imphal to Moreh,” he says. According to him, even before the lockdown, the flow of goods from either side had been slowing due to the general state of the economy. After the pandemic and the closure of the international trading posts, just about 30% of active traders have remained in the business. Those who are still travelling on business in the region have drastically cut down on the number of trips because taxi rates have shot up to ₹500 to ₹700 per person due to the increase in fuel prices.

In the border town of Moreh in Tengnoupal district with a population of about 20,000, the pandemic and subsequent political developments in Myanmar have virtually brought life to a standstill. Inhabitants of the town and neighbouring villages were heavily dependent on border trade. They were mostly engaged in buying, selling, and transporting of goods to the bigger markets in Imphal and elsewhere in the state. Meena Longjam, associate professor at the Manipur University of Culture and an independent filmmaker, who visited Moreh in early June, says, “One of the busiest towns in Manipur looks ghostly. We saw very few commuters, private vehicles and taxis, and the once-busy highway was virtually empty. Earlier, loaded [Tata] Sumos used to streak down this road.”

According to the original agreement, border trade was supposed to take place through customs posts at Zowkhathar in Mizoram and Moreh in Manipur on the Indian side

Additionally, Moreh is now dealing with a large number of displaced people from Myanmar, who crossed the border following last February’s coup. This has put an additional burden on the local population. As a result, Moreh’s populace is relying on humanitarian assistance from philanthropic organisations and charity. Last year, the government of Manipur officially asked the people not to give shelter to refugees but in border towns like Moreh, the local population has deep connections with people on the other who are often family. Under such circumstances, it’s futile to expect people on the Indian side not to provide shelter to those crossing over, using the many jungle routes. A little unofficial trade continues even now through the same routes. The local authorities warn people not to cross the border. “We were advised not to cross the border and if we still went ahead, then it would be at our own risk,” says Longjam.

The closure of the Moreh Gate and the Indo-Myanmar Friendship Bridge means loss of tourist income for the local people. For small businessmen like Mohan, who trades in Indian goods, the prolonged crisis in Myanmar, which is likely to continue in the foreseeable future, means the situation won’t be improving anytime soon. “People on both sides of the Gate are suffering. People from our side used to come to visit Myanmar, but that has stopped now,” he says. Restaurants and hotels that used to serve the tourists are also suffering due to lack of business.

Additionally, Moreh is now dealing with a large number of displaced people from Myanmar, who crossed the border following last February’s coup. This has put an additional burden on the local population

On May 27, the Ministry of External Affairs’ Border Management Division issued an advisory to Manipur Chief Secretary Rajesh Kumar to open Moreh Gate for resumption of border trade. News reports seem to suggest the Indian government has also approached the Myanmar government to open their side of Moreh Gate for resumption of trade.

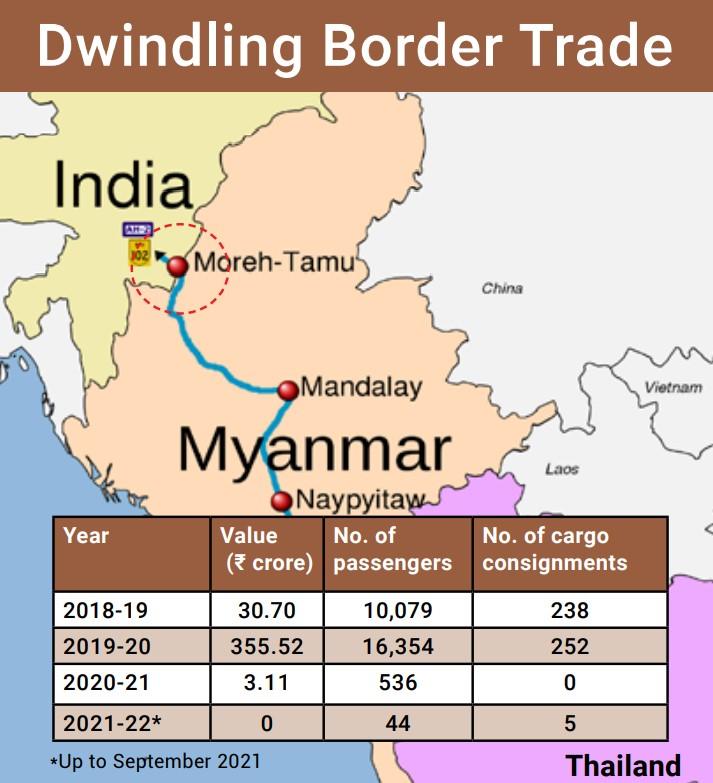

According to the Land Port Authority of India’s website, total trade during 2018-19 was worth ₹30.70 crore and the number of cargo movements was 238 while passenger movement totalled 10,079. The next year, the numbers went up but in 2020-21 they declined sharply to just ₹3.11 crore due to the pandemic. After the Myanmar coup, the value of border trade fell to zero and just five cargo and 44 passenger movements were recorded. Moreover, production in Myanmar has fallen sharply since the military action, resulting in very few goods coming into Manipur. All this while, a trickle of unofficial trade has continued with people from the other side bringing in their loads in the morning and leaving by early afternoon. Over the past month, however, some traders have started setting up small stalls along AH-1 on either side of the border; but the volume of business is extremely low.