Much is being made of a recent finding about India’s fertility rate dropping to replacement level, giving rise to the impression that the country has finally succeeded in defusing the “population explosion bomb”. But has India finally reversed population growth? No black and white answers to this can be given as demographics are a long-term game in which changes take place gradually and are visible after an extended period.

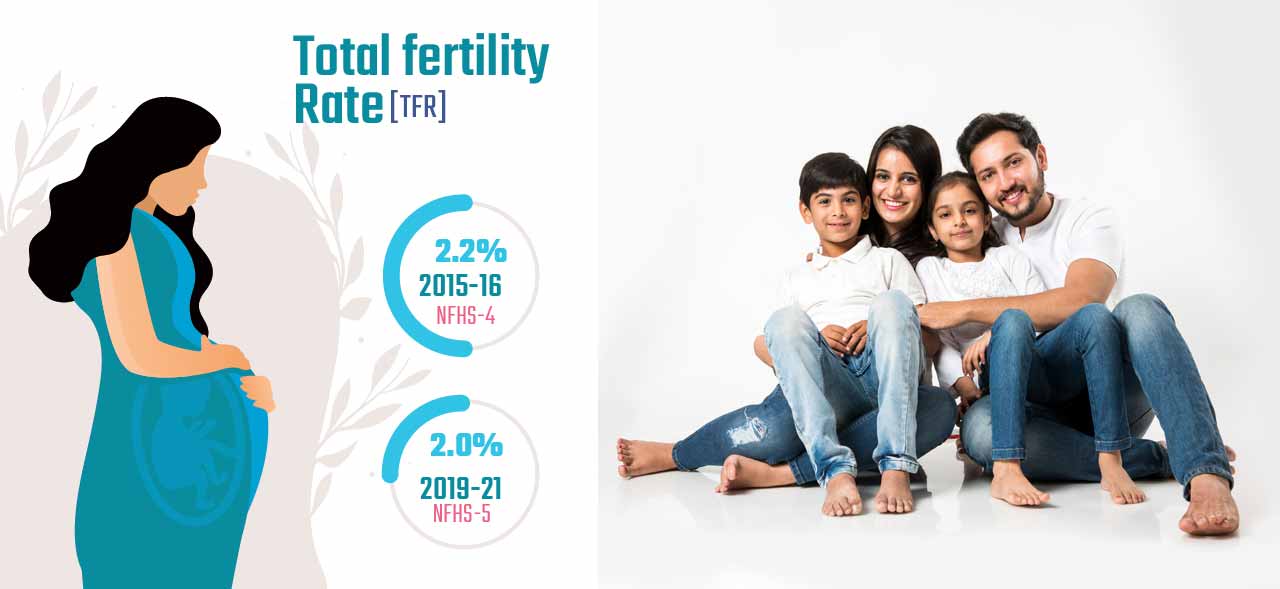

What, then, is to be made of the findings of the survey by the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) that fertility rates in India have dropped to between 2.1 and 2, which represents the “replacement” level of the population? This finding has sparked headlines trumpeting it as marking India’s success in finally beating its over-population problem. But a closer scrutiny of the numbers will reveal that the celebrations could be a bit premature as it may take another half-century before India achieves zero population growth, considered by many as a desirable goal.

Has India reversed its population growth?

Expectations, therefore, that now India will not overtake China as the most populous country within the next decade are quite misplaced. Somehow, being the most populous country in the world is associated with humiliation to be avoided at all costs. The entire issue can be viewed at two levels – one at the level of numbers and resources and the other at a deeper ethical and ideological level.

At the numbers level, the latest calculation of what demographers call total fertility rate (TFR) by the NFHS shows that India’s TFR has fallen to just around two, meaning the level at which two parents give birth to two children. If this continues over time, the population is said to have stabilised, neither growing nor shrinking, a condition that is described as the replacement level.

But just because a TFR of 2.1 has been reached in India, does it mean that its population has stabilised? Or, going a little further, will the population begin to shrink from now on? A closer perusal of projections and figures reveals nothing so dramatic. The only clear conclusion that can be drawn is that TFR has fallen by a factor of four over a longish period of 70 years.

Numbers must include deaths and longer lifespans

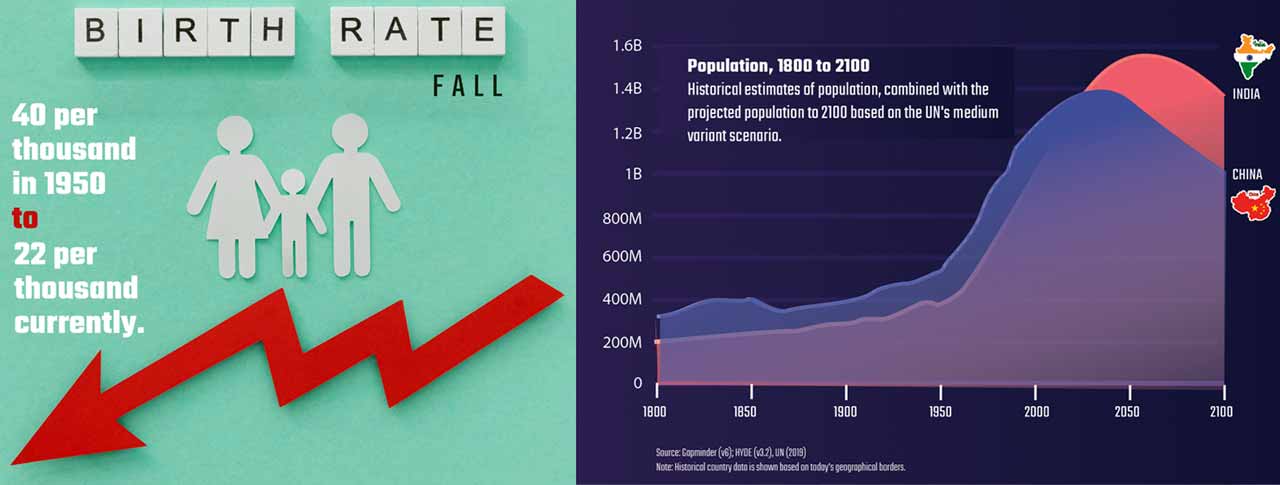

The first census in 1951 revealed a TFR of 6. Since then, even though this number has been continuously declining, the population has nearly quadrupled. This is because there has been a sharper fall in death rates than in birth rates. Death rates have fallen from 28 per thousand to a little over seven per thousand while birth rates have fallen from 40 per thousand in 1950 to 22 per thousand currently. Another factor behind the growth is the increase in life expectancy due to which people live longer than before. In addition, there is the fact that more people are entering child-bearing age, providing what is called the population momentum.

A look at absolute numbers of India’s population growth is revealing. It grew by 78 million people between 1951 and 1961, 109 million over the next decade (1961-71), 135 million over the next (1971-81), followed by 163 million, 181 million and 183 million until 2011 (a total of six decades). The turnaround, if it can be called that, occurred between 1981 and 1971 when decadal growth rates began to reduce. By 1981, the growth rate had dropped by 0.14 percent. In 1991, it was –0.80 percent and in 2001, it was –2.52 percent. Clearly, not only have fertility rates gone down but even population growth had begun to shrink despite a large base year population.

Now let us examine how India’s population is projected to grow over future decades. Projections by the UN’s population division show that during the three decades between now and 2050 India’s population is going to increase by 273 million – on an average less than 100 million a decade. Though the real turnaround occurred after 2011, the growth rate in percentage terms had started to fall way back in 1981, a good four decades back. These figures make it clear beyond a doubt that it takes several decades before the effects of falling fertility rates kick in to get reflected in population growth (or decline).

Expectations, therefore, that now India will not overtake China as the most populous country within the next decade are quite misplaced. Somehow, being the most populous country in the world is associated with humiliation to be avoided at all costs.

Population control often leads to human rights violations

But the question of population as an important issue in human affairs began to occupy public mind space fairly recently in history. The spectre of increasing population becoming a threat to the survival of the human race was first raised by an Anglican clergyman, Thomas Malthus, in the closing years of the 18th century. Based on some basic statistics, Malthus made the dire predictions of overpopulation that would only be brought in check by natural calamities like famines, diseases and other disasters. Otherwise, he said the Earth would soon run out of food.

Malthusian fears, however, proved unfounded and receded into the background due to rising standards of living and nutrition. The prophesied population doom did not overtake humanity. Large-scale migrations from Europe to the Americas and other parts of the world also played a part, relieving the population pressure on Europe. But fears of overpopulation did not die down altogether and were revived in the second half of the 20th century as many newly independent countries in Asia and Africa embarked on the road to development. Populations naturally grew following rising life expectancies and falling mortality rates with improved healthcare under self-governance. But Western countries began to view this as a threat, particularly from countries with large populations like India and China which between them accounted for about a third of the world’s population and still do.

The 1951 census recorded a TFR of 6. While the number has declined since, the population has almost quadrupled due to sharper fall in death rates, rise in life expectancy and more people entering child-bearing age.

Ever since, the world has become divided between those who call for energetic international efforts to control rapid population growth and those who oppose any such action. In recent times fears about this were dramatically articulated by American biologist Paul Ehrlich who became a latter-day Malthus when he published The Population Bomb in 1968 that soon became a bestseller. Shortage of food could no longer be held out as logic so a new one was found – burgeoning populations would trigger an ecological disaster that would kill millions of people in the 1970s and ’80s, Ehrlich forecast. This argument was soon taken up by new groups who gathered under the umbrella of environmentalism.

In the meantime, Western apprehensions too took concrete shape. In 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson made American foreign aid dependent on recipients adopting family planning programmes, fearing that the US could be threatened by the desperate masses. A few years later, during the administration of Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, a report was issued in 1974 by his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, about the necessity of helping poorer nations to keep their populations under control. This was in the interest of the US, said the Kissinger report, as it was necessary to preserve stability in the countries supplying essential minerals for American needs. The report also expressed concern about the growing number of youths supporting anti-imperialist movements. India, incidentally, was one of the 13 countries identified by the report where population control measures were to be encouraged.

It was in the same year that a World Population Conference was held in Bucharest, Romania, which wanted developing countries to put in place population policies to influence the demographic process. The growing number of people related to the slow rates of development. The recommendations included one which stressed the need for reconciling “individual reproductive behaviour and the needs and aspirations of society”.

Soon afterwards, India became the first country to introduce coercive family planning in 1975 during the Emergency. The backlash to the forcible vasectomies and sterilisations brought down the Indira Gandhi government at the polls. Subsequently, not only was the programme itself renamed but governments have handled population control policy issues with kid gloves ever since. Though the coercive programme was called off in India in 1977, barely two years later it was introduced in China, with Western blessings, as the draconian one-child policy. The West had looked away from gross human rights violations under this programme as it had been unnerved by the massive size of the Chinese Army during the Korean War in the 1950s which had inflicted several reverses on US-led UN forces. It was not until 2015 that China officially ended the policy, alarmed at the prospects of a sharp fall in the 0-14 age group – indicating a future ageing population.

India became the first country to introduce coercive family planning in 1975 during the Emergency. The backlash to the forcible vasectomies and sterilisations brought down the Indira Gandhi government.

The population control lobby has found a convergence of views on its family planning policy with gender rights, pro-choice and human rights groups. Family planning efforts mostly revolve around birth control methods, including contraception and abortion of unwanted pregnancies. Opposition to family planning comes mostly from pro-life religious groups who have ethical objections mainly to abortion. While the population control lobby seems to be losing momentum the debate continues between pro-life and pro-choice lobbies. This debate is raging once again in the United States over abortion and planned parenthood rights of women provided by earlier rulings of the American Supreme Court. In the meantime, the debate over whether governments should interfere with the procreation system of human populations goes on in many other parts of the world.