Avinash, 42, stood at the edge of his seven acres of farmland at Orhanpur village in Nawada district of Bihar, staring at what could have been land full of paddy swaying in the light breeze, golden in the reflection of the rising sun. Despite being barely 10 km from the district headquarters and situated close to a rivulet, he could sow paddy in less than three-quarters of the land due to the significantly delayed monsoon this year. A deficient monsoon in the sowing period, followed by excess rainfall around harvest time, played havoc with the crops of food which most farmers this kharif season.

What is ironic in Avinash’s case is that until about five years ago, he was running a franchise of four junior schools in the National Capital Territory. First, demonetisation, then the Covid-19 pandemic forced him to put the lock on all but one school. To earn a living, he turned to farming and shifted base to his ancestral village in Bihar.

“My total average income (from farming) in a year is about ₹2 lakh to ₹2.25 lakh. However, the costs incurred to grow crops on my land are around ₹80,000 to ₹90,000 a year. So the income from farming is obviously hardly anything to lead a life,” Avinash says ruefully.

In the adjacent state of Jharkhand, farmer Suphal Mahto of Maheshpur village in Ranchi district is also staring at an estimated crop loss of about 50% this year. This, when his village lies barely 50 km from the capital, Ranchi, and he enjoys the advantage of having his land irrigated by a nearby canal, unlike several other farmers in the state.

“Sowing (of kharif rice) should have been over by mid-August. But due to the rains playing truant, it went on till early September this year,” he said. According to Mahto, the fall in acreage of kharif (monsoon) crops is due to the rains playing truant initially. And desperate farmers who sowed paddy even during the early September showers are not getting enough produce out of their land.

“This is the situation across the state. It’s only fields where water accumulated naturally that witnessed average produce. In fact, many farmers have migrated to cities in search of means of sustenance,” Mahto points out.

Grain stock – Food Security

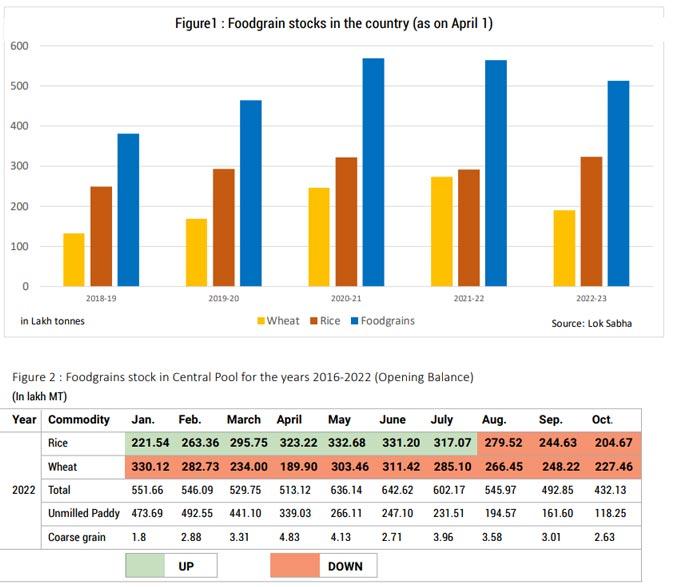

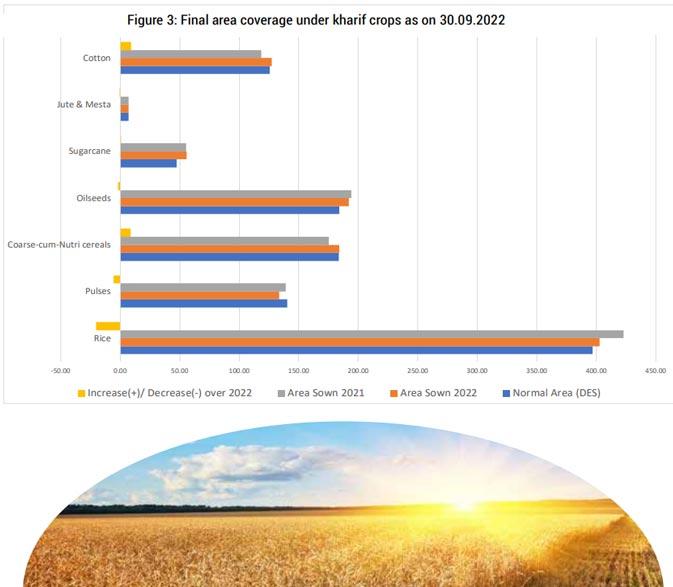

The Centre has repeatedly assured that there is enough food grain and that stocks in the country are not at a 15-year low as is the belief in certain quarters (see Fig. 1). However, if we take a look at major crops like rice and wheat—the staple diet for most people in our country—there is a noticeable drop beginning August 2022, which dwindles further till October in the central pool. Food Corporation of India (FCI) data shows a significant fall in the stock of wheat, beginning May 2022 (Fig. 2). Also, according to the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, as of September 30, the final area coverage under kharif crops in 2022 stood at 1,102.79 lakh hectares against 1,112.16 lakh hectares last year, registering a decrease in acreage of 9.37 lakh hectares (Fig. 3).

About 402.88 lakh hectares area coverage under rice was reported this year compared to 423.04 lakh hectares in the corresponding period in 2021, which is 20.16 lakh hectares less. Higher acreage was reported from Telangana (up by 97,000 hectares), Haryana (94,000 hectares), Gujarat (51,000 hectares), Rajasthan (37,000 hectares), Himachal Pradesh (14,000 hectares), Maharashtra (8,000 hectares), Tamil Nadu (4,000 hectares), Jammu and Kashmir (4,000 hectares), Uttarakhand (3,000 hectares) and Arunachal Pradesh (3,000 hectares).

But most states known as major producers of rice which faced the vagaries of nature reported lower coverage. Among these are Jharkhand (down by 9.22 lakh hectares), West Bengal (3.65 lakh hectares), Uttar Pradesh (2.48 lakh hectares), Madhya Pradesh (2.24 lakh hectares), Bihar (1.97 lakh hectares), Andhra Pradesh (1 lakh hectares), Assam (99,000 lakh hectares), Chhattisgarh (74,000 lakh hectares), Tripura (21,000 hectares), Meghalaya (21,000 hectares), Nagaland (21,000 hectares), Odisha (20,000 hectares), Punjab (12,000 hectares), Karnataka (7,000 hectares), Goa (3,000 hectares), Mizoram (3,000 hectares), Kerala (2,000 hectares) and Sikkim (1,000 hectares).

As evident from the Central government’s figures, the acreage of rice has been significantly reduced this year. The exact amount of produce will be known once procurement for this season begins in full swing.

However, if we take a look at major crops like rice and wheat—the staple diet for most people in our country—there is a noticeable drop beginning August 2022, which dwindles further till October in the central pool. FCI data shows this fall

Similarly, about 133.68 lakh hectares of coverage under pulses has been reported compared to 139.21 lakh hectares in the corresponding period last year, a fall of about 5.53 lakh hectares. The states that reported higher coverage were Madhya Pradesh (by 4.08 lakh hectares), Uttar Pradesh (23,000 hectares), Chhattisgarh (12,000 hectares), Assam (11,000 hectares), Tamil Nadu (8,000 hectares), West Bengal (6,000 hectares), Jammu and Kashmir (6,000 hectares) and Nagaland (2,000 hectares).

On the other hand, lower acreage was reported from Maharashtra (by 3.51 lakh hectares), Telangana (1.74 lakh hectares), Jharkhand (1.29 lakh hectares), Karnataka (97,000 hectares), Gujarat (84,000 hectares), Rajasthan (67,000 hectares), Haryana (38,000 hectares), Andhra Pradesh (32,000 hectares), Bihar (25,000 hectares), Uttarakhand (17,000 hectares), Odisha (12,000 hectares) and Tripura (3,000 hectares).

In oilseeds, about 192.14 lakh hectares area coverage has been reported compared to 193.99 lakh hectares in the corresponding period last year, which is 1.85 lakh hectares less. The states where a higher area was reported were Maharashtra (by 2.44 lakh hectares), Rajasthan (1.28 lakh hectares), Uttar Pradesh (26,000 hectares), Telangana (17,000 hectares), Nagaland (9,000 hectares), Assam (8,000 hectares), Bihar (6,000 hectares), Manipur (2,000 hectares), Jammu and Kashmir (1,000 hectares) and Arunachal Pradesh (1,000 hectares).

In comparison are Madhya Pradesh (down by 3.05 lakh hectares), Gujarat (1.55 lakh hectares), Andhra Pradesh (59,000 hectares), Odisha (51,000 hectares), Chhattisgarh (31,000 hectares), Haryana (8,000 hectares), Karnataka (7,000 hectares), Jharkhand (6,000 hectares), Tamil Nadu (4,000 hectares) and Tripura (1,000 hectares).

Fall in kharif acreage

The figures from the states show that there has been a fall rather than a significant boost in acreage under oilseeds and pulses. Nature seems to have played spoilsport regarding the government’s plan for a thrust in production of the two items to reduce dependency on imports. According to the former Union minister of state for agriculture, Sompal Shastri, “We need to ensure that there is enough foodgrains. There is still an imbalance, we continue to import oilseeds and pulses to meet domestic requirements.”

For the past six years, the Centre has outlined the thrust on increasing productivity of oilseeds and pulses to achieve self-sufficiency. This was also stated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his speech to mark the 75th anniversary of independence. He pointed out India’s self-sufficiency in foodgrains, which shows that it can reduce its dependence on other imports. “When our country needed food, we didn’t outsource it, rather our countrymen decided to grow food for our people and we have managed to achieve it,” said the prime minister. But achieving self-sufficiency in all food items will need a stronger and more concerted attempt. While India is largely self-sufficient in the case of foodgrains and many items like milk, fruits, and vegetables, as pointed out by Shastri, we depend on imports for edible oils and pulses.

According to NITI Aayog estimates, India will have a surplus of foodgrains, milk, fruits, and vegetables but it will be largely deficit in oilseeds in the future.

Crops that are not entirely dependent on the monsoon or excess water did better this season. Going by acreage, about 55.73 lakh hectares under sugarcane has been reported compared to 55.22 lakh hectares in the corresponding period last year: a hike of 51,000 hectares. The same happened with cotton: about 127.50 lakh hectares has been reported under cotton compared to 118.59 lakh hectares in the corresponding period last year, which is an increase of 8.92 lakh hectares.

Hunger Games

India was ranked 107 out of the 121 assessed countries in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2022 released in mid-October. The GHI tracks and measures hunger across the world following certain criteria and inputs sourced from various countries. The overall score of 29.1 categorised India at the “serious” level.The report pointed out that South Asia and Africa South of the Sahara are dangerously off-track in terms of the progress needed to achieve the second Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger by 2030. India, however, issued a strong rebuttal, calling it another “consistent effort” to “taint India’s image as a nation that does not fulfil the food security and nutritional requirements of its population”.

Indeed, food security is a flexible concept, as reflected in the many attempts at definition in research and policy usage. In its policy brief of June 2006, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations defined the following dimensions of food security:

- Food availability: The availability of sufficient quantities of food of appropriate quality, supplied through domestic production or imports (including food aid).

- Food access: Access by individuals to adequate resources (entitlements) for acquiring appropriate foods for a nutritious diet. Entitlements are defined as the set of all commodity bundles over which a person can establish command given the legal, political, economic, and social arrangements of the community in which they live (including traditional rights such as access to common resources).

- Utilisation: Utilisation of food through adequate diet, clean water, sanitation and health care to reach a state of nutritional well-being where all physiological needs are met. This brings out the importance of non-food inputs in food security.

- Stability: To be food secure, a population, household or individual must have access to adequate food at all times. They should not risk losing access to food as a consequence of sudden shocks (e.g., an economic or climatic crisis) or cyclical events (e.g., seasonal food insecurity). The concept of stability can therefore refer to both the availability and access dimensions of food security.

The Centre is said to be waiting for reports from the states on the extent of crop damage due to untimely rain. Agreeing that there had been crop damage this season, Union Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar recently said that agriculture was vulnerable to unpredictable rain. He added that compensation, if any, can be decided only after following due procedures based on reports from the states. He explained that there were Disaster Relief Funds in states for providing compensation to farmers and, if necessary, money from the National Disaster Relief Fund would be released. Such actions will be considered only after damage assessment by the states.

During the sowing season, farmers worried over the late monsoon had raised the issue of inadequate rainfall—especially in Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and such states—which many claimed was creating a drought-like situation in 85% of the country. Farmers had also demanded that drought be officially declared in about 196 of the affected 660 districts.

The Centre is waiting for reports from the states on the extent of crop damage due to untimely rain. Agreeing that there had been crop damage this season, the Union agriculture minister said that agriculture was vulnerable to unpredictable rain

Food availability

Given the extent of acreage of kharif crops and the foodgrains stock in the central pool, is the country facing a shortage? Shastri feels there is still enough in stock. The Green Revolution of the 1960s not only catapulted India to a leading producer but ensured food sustenance for years to come. However, he has pointed out that the powers that be need to take stock of the situation and make concerted efforts to stave off any untoward situation.

“You can say that the concern is more about malnutrition than starvation. The Russia-Ukraine war will not have such a fallout (on us) as it has had in some countries,” says the former minister. The war has adversely affected the import of foodstuff and fuel in several countries especially after the imposition of sanctions against Russia.

Reiterating Shastri’s views that the war will not directly affect India, Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) leader Badri Narayan Choudhary expressed concern that the government has not taken into account the subsequent damage caused by widespread inundation in some states. “I fear we may lose half the total production of most crops this year due to the dual vagaries of nature,” he says. This concern was echoed by Raju Shetti, founder of Maharashtra’s Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana. “The figures reflect part of the scenario. Even those farmers who somehow managed to sow, lost their crop to the devastating floods. The situation is particularly bad in Vidarbha and Wardha,” he says. Besides Vidarbha and Wardha, late rains have severely affected areas in Gadchiroli, Chandrapur and Yavatmal in Maharashtra.

According to India Meteorological Department (IMD) data, the dry spell in the sowing season was followed by 80% excess rain in the 10-day period of the “post-monsoon” season between October 1 and 10. It is still too early to determine the acreage under rabi crops. Sowing of wheat has not yet been reported, as stated in a preliminary report of rabi area coverage released by the government as of October 14. While about 1.25 lakh hectares has been reported under rabi rice (55,000 hectares over last year’s corresponding figure), acreage for oilseeds and pulses is also more by 3.63 lakh hectares and 99,000 hectares, respectively.