On November 1, 2021 Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow that India will achieve the target of net zero emissions by 2070. Seven years earlier, on August 15, 2014, delivering his first Independence Day address as prime minister from the Red Fort’s ramparts, Modi had given a call to Indian entrepreneurs to adopt a ‘zero defect, zero effect’ mantra in their production—a direct reference to the need to make things without causing environmental harm.

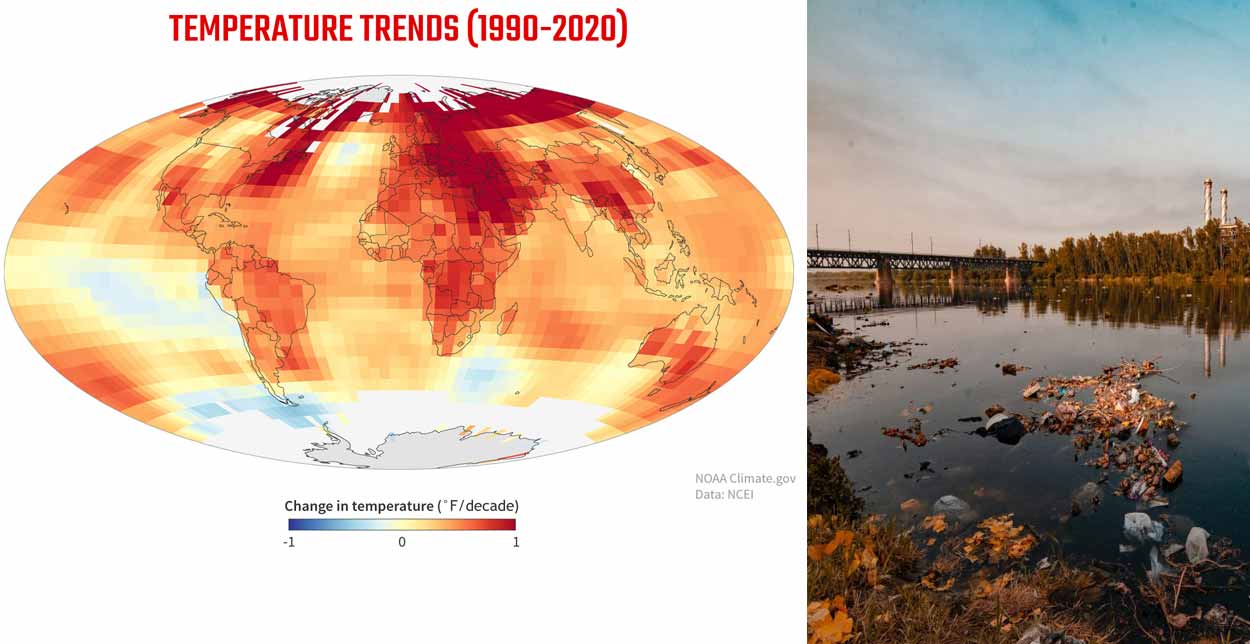

This November, large parts of Tamil Nadu have reeled under a wave of floods that brought a bustling metropolis like Chennai to its knees. Elsewhere, in Delhi and the National Capital Region (NCR), people are gasping for breath with air quality plummeting to extremely hazardous levels.

It is easy to be dazed by the impact of climate change that has reached our homes. But everyone—governments, companies, politicians, and consumers—needs to act now. Avoiding build-up of industrial and household waste is a good starting point.

India’s time for a ‘circular economy’ has come. This has to be brought about through strict enforcement, strong people’s participation and proactive corporate involvement.

How do we prolong the lifecycle of products, recondition them and cut down on waste generation? There are examples that India can, and needs to, draw upon.

A.P.C., a French denim brand, takes back used pairs from consumers, repairs them if necessary, and sells them under what is branded a ‘butler service’. In some municipal facilities in Europe, consumers don’t own or buy lighting products. For instance, in some such areas, Dutch lighting and electronics maker Philips instals, owns and services lighting for consumers. The consumers pay for the services, and at the end of the service contract the lighting systems can be upgraded and reused, or all materials and parts can be returned for repurposing or recycling, minimising material waste.

Sweden’s H&M, a mass retail apparel brand, has a worldwide policy of offering consumers who return its old garments discounts on new ones; it reconditions the old ones to sell at cheaper prices, thus prolonging the lifecycle of the fabrics and fibre used.

According to Jocelyn Blériot, executive officer of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “several building blocks of circularity are deeply ingrained in Indian habits, as exemplified by the high rates of utilisation and repair of vehicles and the distributed recovery and recycling of materials post-use.

“Often handled informally, these activities provide the only source of livelihoods to some of the poorest populations. By turning these existing trends into core development strategies, India could generate significant economic savings, massively cut down on carbon emissions,” Bleriot wrote in a blog for the World Economic Forum.

India’s time for a ‘circular economy’ has come. This has to be brought about through strict enforcement, strong people’s participation and proactive corporate involvement.

In India, the environment ministry has aimed to double the recycling rate of key materials to 50 percent in the next five years and enable upcycling of waste.

Smart thinking needed

A truly circular economy, however, would need more than a policy framework. It will also require nimble, `smart’ thinking.

Factories that use large amounts of water should be necessarily made to take a variety of steps to save energy and improve efficiency. Using a turbine to generate power from the water used at a factory for things like cooling, air conditioning, or for generating power at a food processing factory from biogas produced from organic waste, should be made mandatory.

For example, factory energy management systems (FEMSs) should gradually be made compulsory, to identify all the different forms of power consumption and perform centralised management in conjunction with the factory’s production plans to ensure that electric power is used efficiently.

Consumer durable makers would have to produce items, keeping in mind their recyclability value. Consumers should get used to paying for the service of a product, rather than owning a product and then throwing it away later. It will require a mindset change. But it’s worth it. Gradualism is passé. It’s time to go for broke.

While India’s ‘net zero’ deadline is two decades later than the deadline that the United Kingdom (UK) has set and a decade later than China’s, this is the first time India has set a target for achieving net-zero goals.

This is a big step forward in two ways. One, India, the world’s fourth-largest polluter after the US, China, and the European Union, has set a clock for itself and the world to make the planet’s atmosphere less toxic. Two, the prime minister announcing the goal on the world stage brings in an element of domestic political commitment.

In many ways, Modi’s net-zero declaration by 2070 is as much a demonstration of the government’s political intent to walk the talk on climate change as it is about setting a goal to conform to a global initiative amid increasing focus on getting countries to set targets for themselves to reach net-zero carbon emission.

For its part, over the last few years India has sought to set an example in the transitioning to clean energy through a clutch of initiatives, including setting up of the International Solar Alliance (ISA), raising the domestic renewable energy target to 500 GW by 2030, creating one of the world’s largest markets for renewable energy, putting in place an ambitious National Hydrogen Mission and continuing efforts to decouple its emissions from economic growth. There has also been considerable progress in seeking to give access to electricity to all households.

India faces a peculiar paradox in balancing its economic growth ambitions while still being on the correct side of the climate change fence. “Our manufacturing should have zero defects so that our products should not be rejected in the global market. Besides, we should also keep in mind that manufacturing should not have any negative impact on our environment,” Modi had said in 2014.

In Glasgow, the PM coined a new acronym—LIFE, shorthand for Lifestyle for Environment—to combat climate change. “Today it is necessary that all of us come together as a collective partnership and take LIFE forward as a movement. It can be given an institutional framework and become a mass movement for an environmentally conscious lifestyle,” he said.

Everybody’s game

While there is no gainsaying the government’s commitment towards climate-friendliness in terms of enabling policies and laws, the responsibility of execution lies squarely with industry through collaborations with the government, civil society, and the citizenry to help India achieve its commitments.

Businesses will have to draw up a growth strategy that is timescale consistent with the response to climate change, water scarcity and other global challenges. Sustainability, the buzzword across the world today, will have to take on a new avatar and become the soul of every organisation—business or otherwise. Businesses cannot succeed in societies that fail. Corporates, as large economic organs of society, will need to play a transformative role in securing the future of the generations to come. It is increasingly clear that sustainability can no longer be a choice but an integral part of business strategy.

In the final analysis, profit maximisation and sustainability will have to be mutually complementary goals. This will require a pivotal swing from the current mode of gradualism to a big-bang approach anchored on sustainability and innovation. Smart business is about adapting the marvels of technology through models that are scalable, profitable and, importantly, ecologically and socially more sustainable.

Rapid innovation in new frontiers of nanotechnology and biotechnology can potentially help produce goods that are stronger yet lighter and more efficient than their earlier generation.

In India, the environment ministry has aimed to double the recycling rate of key materials to 50 percent in the next five years and enable upcycling of waste.

With the prime minister stating the goal loud and clear, it is now for stakeholders from across the spectrum to deliberate on innovative partnerships that can accelerate the energy transition, and the gaps that need to be plugged to ensure energy security, industrial acceleration and also achieve India’s climate change targets vis-à-vis COP26.

This is the time for the industry to hold up the mirror and take a long, hard look at itself. A fundamentally new model of industrial organisation is needed to de-link rising prosperity from resource consumption growth—one that goes beyond incremental efficiency gains to deliver transformative change, but evolves into a new B2C approach: Business to Climate.

(Gaurav Choudhury is a senior journalist and founder and CEO of Earshot Media, India’s first Dolby Atmos-powered podcasting platform for audio originals)

By Gaurav Choudhury