Nothing has brought the digital divide into sharper focus than the Covid-19 pandemic. The topic of the divide had been hitherto limited to academic circles, and was sometimes highlighted in the media. Those with access to the internet—the most ubiquitous symbol of the digital world—were not too bothered about those without it, while those who did not have access to it did not think it made much of a difference. The pandemic has changed all that. We seem to have entered a new world in which the digital divide impacts people on both sides of the fence in more ways than imagined.

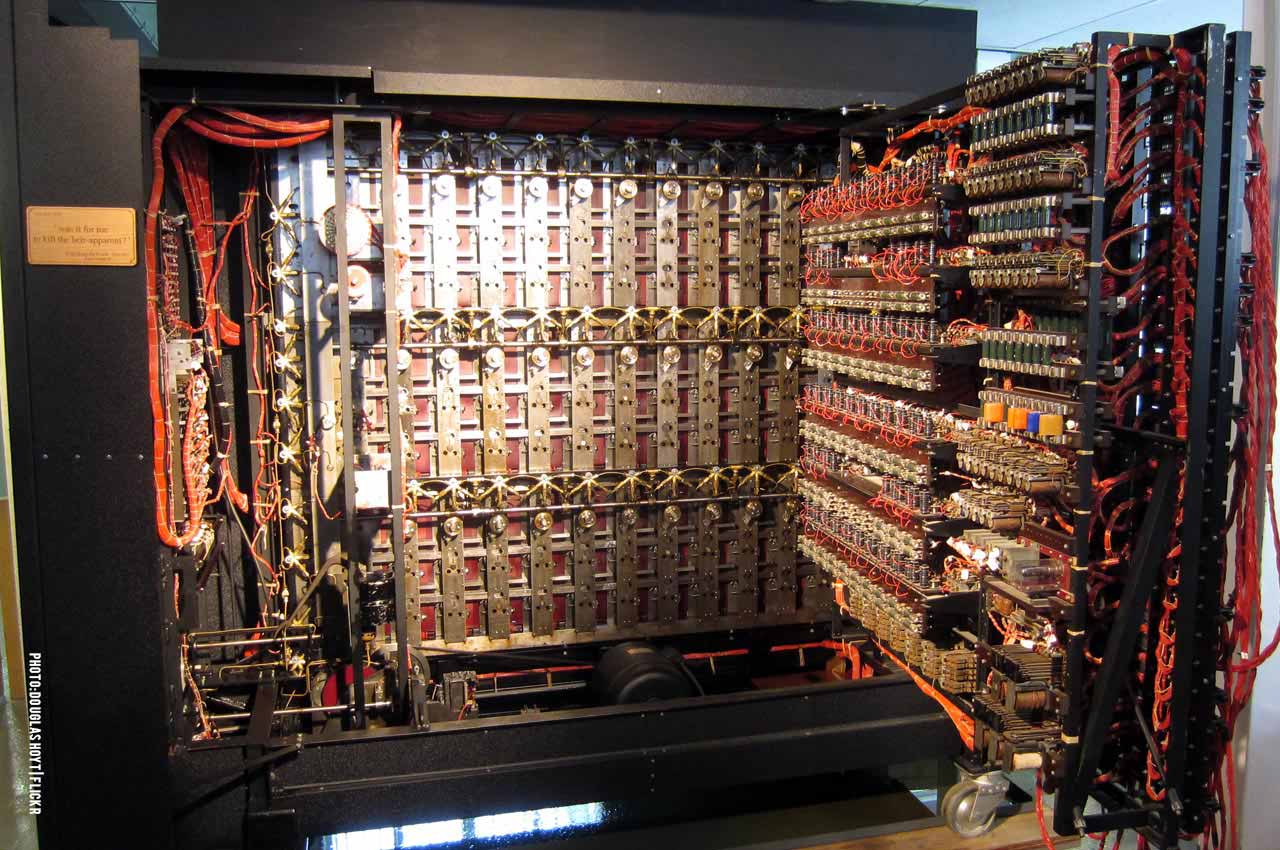

To understand the origins of the divide, it would help to recall the days when the first computers, as we know them today, were built. As British engineers designed machines to crack the complex German Enigma codes during World War II, some of them were struck by the idea of constructing a machine that could replicate the human brain. Some of the best known among them were British mathematician Alan Turing and Hungarian-born American mathematician John von Neumann.

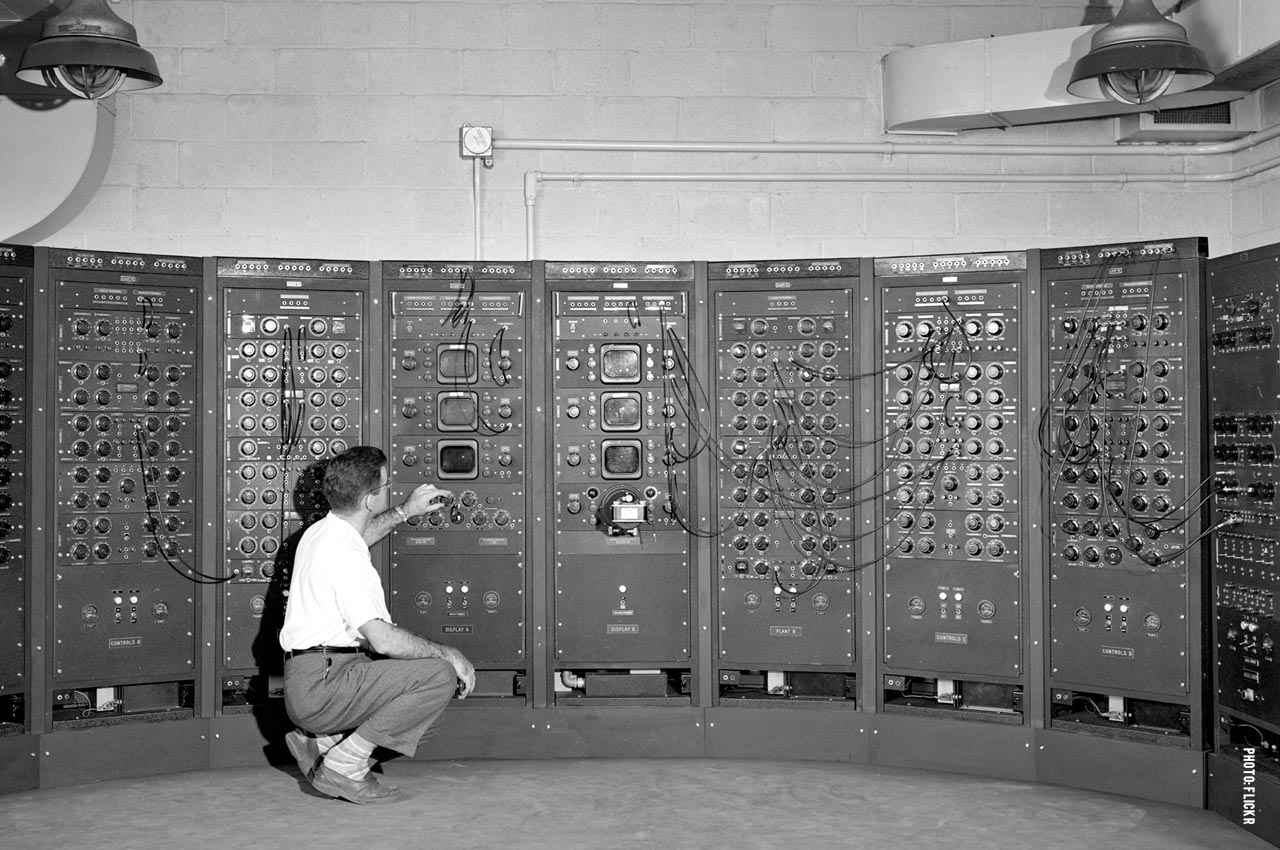

While Turing’s ideas and machines did not get much publicity due to the Official Secrets Act that was in force in Britain, Neumann faced no such constraints in the United States. He built a machine with the help of vacuum tubes, which could be made to resemble the two states of neurones—excited and relaxed. In the case of the vacuum tubes, it would be ‘on’ or ‘off’ and would use only two numbers—0 and 1. The digital age can be said to have started during these years. The machine designed by Neumann, called MANIAC-1, could carry out complex calculations at high speed that were required in the development of the H-bomb.

It proved useful to the American military but was not suited for general use since it weighed half a tonne. And it was expensive. At that time private companies that built computers rented them out for anything between $10,000-20,000 a month. This clearly was not something that could be sold in a department store. Only governments and universities could afford to build and maintain them. This was the earliest instance of the digital divide: between the experts and the rest.

Miniaturisation made wider use of computers possible and the key role in this regard was played by materials that have come to be known as semiconductors. These materials are distinguished by the fact that they are partial conductors of electricity. First noticed at the cusp of the 20th century, they were used at that time to initiate wireless communication that eventually overtook cable telegraph. Silicon, that makes up a large part of sand, was found to behave as a semiconductor when it had some impurities. It was abundantly available and silicon-based transistors replaced vacuum tubes, making computers and other electronic devices much smaller than before and cheaper.

Silicon transistors were followed by further miniaturised silicon integrated circuits (IC) or chips that form the building blocks of computer hardware. Over the decades, transistors have been shrinking at a remarkable pace to an extent such that with today’s technology it is possible to squeeze in as many as 20 billion transistors on a fingernail-sized chip, immensely increasing the per square inch capacity of all electronic devices, starting from simple calculators to complex robots.

MANIAC-1 proved useful to the American military but was not suited for general use since it weighed half a tonne. And it was expensive. At that time private companies that built computers rented them out for anything between $10,000-20,000 a month. This clearly was not something that could be sold in a department store

This is the technology that is powering the information technology (IT) age in combination with the internet over the past 30 years. It made possible mobile phones, laptops, tablets, bank transactions, e-commerce, social media, email, the stock markets, advanced automobiles, defence equipment, trains, ships, aircraft and, of course, cloud computing. The digital domination is complete. So great is the thrall in which digital technology is held by the younger generation that in their imagination the world of their parents, devoid of mobiles, social media and computers, actually belongs to an era derisively labelled ‘primitive’.

But wait a minute, is that so? As the digital age has progressed, its downside, parts of it serious, have also surfaced, something that the generation weaned on computers and mobiles, with its limited experience, is usually unaware of. Perhaps the devastation wreaked by the Covid-19 pandemic will force the ‘digital age kids’ to view their ‘digital God’ with an altered perspective. While the novel coronavirus itself has been most ‘democratic’, it has struck down people regardless of their nationality, education, gender and income, its consequences are underlining the digital divide with a red line as it hit the most vulnerable the hardest. In India, access to some of the most important services is rooted directly in disparity in accessing the internet. This has adversely affected two crucial areas—healthcare and education, where major gaps have already existed for years. After the Covid-19 pandemic came knocking on our doors, this divide has widened even more. The impact of this divide is generational and will snowball exponentially in the decades ahead.

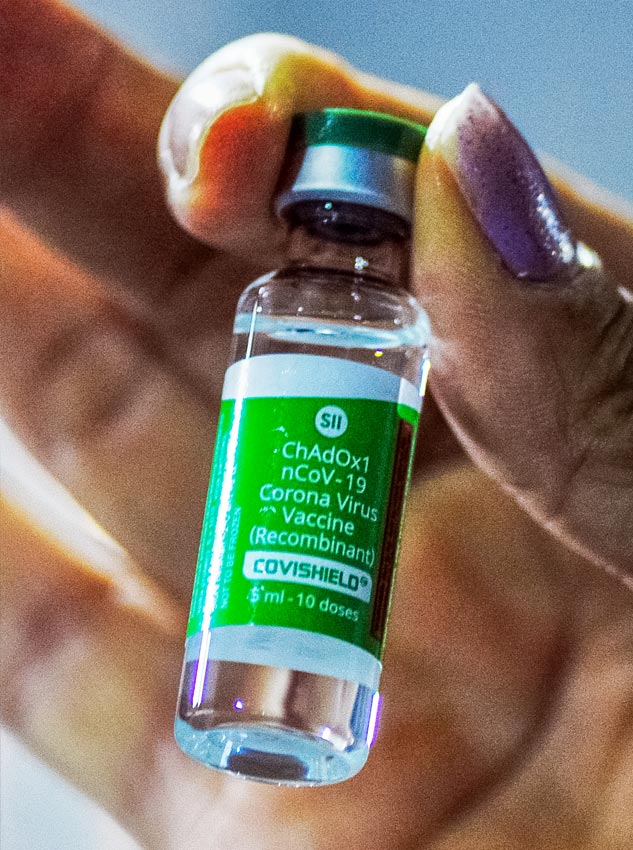

The debate around healthcare today is dominated by Covid-19. The only answer to the virus is mass vaccination, which is vital for the physical well-being of Indians which in turn will permit reopening of the economy. The devastating second wave of the pandemic has raised the spectre of more waves recurring with accompanying disruptions. The American experience has shown that the earlier the bulk of the population is vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, the easier it will be to end crippling lockdowns. Already the economic divide has created a “two-track pandemic” with rich countries having far greater access to vaccines than the poorer regions of the world.

This has enabled the United States, for example, to vaccinate 86 out of every 100 of its population, while in India this figure is just 14 per 100 as of mid-June. The World Health Organisation, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation have warned that the divide could leave millions vulnerable to the virus. This will allow deadly variants to emerge and ricochet across the world. The digital divide poses a similar threat within India.

Though vaccination got off the mark in January, access to vaccines is limited to those with internet access and mobiles. Less than half of India has access to the internet of whom nearly two-thirds live in the cities. Registration for the vaccine can only be done online and a mobile phone is mandatory. Though it is possible for up to four people to register from a single mobile phone, the bias is weighted in favour of those familiar with operating mobiles. In times of vaccine shortage, the system automatically works on a first come, first served basis. The greater the barrier to digital access, the greater the difficulty in getting the shots.

Millions, therefore, are at risk of remaining unvaccinated, delaying India’s journey towards herd immunity for which at least 80 to 85 percent of the population needs to be immunised. If some of those left out succumb to the disease in the meantime, the virus gets more scope to mutate into more dangerous variants. We are already seeing further mutations of the Delta variants that caused the second wave in India. This increases the risk of further outbreaks, lockdowns, and economic downslide. The ramifications of the digital divide coupled with vaccine shortage extend way beyond India’s borders.

Covid-19 has made it clear that no health system, even the best in the world, is capable of stopping a pandemic of this magnitude. Even the United States, which spends 8.5 percent of government spending on health, is still reeling from the worst impact of the pandemic. India, in comparison, with four times the population of the US, spends about around one percent of its GDP on healthcare. No wonder people faced severe shortage of hospital beds, medical supplies, and oxygen at the height of the second wave. Since immunisation seems to be the only option, the need of the hour is to overcome the digital divide.

The other area that has been adversely affected by the digital divide is education—not of as immediate concern as health, but vitally important for the country’s future. According to estimates by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1.6 billion students were locked out of their schools globally. Institutions turned to online teaching in an effort to maintain continuity of learning. But here again the digital divide has kept out students who do not have access to the internet or had slow connections. Even those with access to the internet, both students and teachers, quickly realised that online education is a poor substitute for classroom teaching. These students may not miss out on learning completely, but the quality of their learning is poor. For those who have no access to the internet or are unable to keep up because of slow internet speeds, the closure period is certain to be a total loss.

Registration for the vaccine can only be done online and a mobile phone is mandatory. Though it is possible for up to four people to register from a single mobile phone, the bias is weighted in favour of those familiar with operating mobiles. The system automatically works on a first come, first served basis

In India, as in several other countries, many of these students with no access to the net will fall behind in acquiring skills that would help them contribute to the economy since they missed an entire term of schooling. And the worrying thing is that what these young students have missed will show up years down the line and the cumulative effect of this disempowered group will be devastating in the future. Most certainly, those who have missed out on learning during the pandemic will have a far lower potential for optimum wages, which could last their lifetimes. In India, it seems the Covid-19 pandemic has combined with the digital divide to deliver a double whammy.

The writer has been a media professional for 38 years. He was the former HoD of the Amity School of Communication, Amity University.