For some time now, an air of apprehension has grown in some global sections over the formation of the China-Russia-Iran-Pakistan grouping. This is being considered a palpable challenge to the existing geopolitical ‘Quad’ of Australia, India, Japan, and the US.

The new diplomatic quartet, argue some experts, is based more on specific regional interests, and not on international issues. At a theoretical level, it lacks the globalised tenets of diplomacy, cooperation, and inherent principles. However, at stake, among other geopolitical interests, is Central Asia – and particularly the region conveniently surrounded by the China-driven Quad, which has witnessed several vicissitudes through time. On the radar of both the quartets is the prominent landlocked country, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, which is at the crossroads of Central and South Asia.

From the English writer Rudyard Kipling to India’s Rabindranath Tagore, the Afghans were portrayed as aggressive, sometimes vengeful and revengeful, communities of tribes. Though Tagore’s short story, Kabuliwala, largely personified an emotional, caring Afghan, but for one physical assault on a debtor, Kipling’s poem, The Young British Soldier, closes with the gory depiction of Afghan women who “cut up what remains” of a wounded enemy.

The Afghans themselves have witnessed several invasions and intrusions. For centuries, their country underwent consecutive wars by outsiders such as the Persians and Greeks, followed by Arabs, the Turko-Mongol conqueror, Timur, the Mughals, and the erstwhile USSR. Then it was the turn of the Americans to occupy their land to create peace. Now, it is time for the US and other allied forces to pull out of the country after almost a decade of considerable military presence.

Add to this the complexity of social diversity. Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic, and mostly tribal society. The population comprises Baloch, Hazara, Nuristani, Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek people, among others. Pashtun is the dominant group among them. The diversity has been used by the conquerors to divide the people, and goad and encourage them to fight one another.

This history was chronicled by Peter Hopkirk, who authored the book, The Great Game, in the last century. He wrote extensively about the diplomatic significance of Afghanistan for major nations such as Russia and Britain, and documented the overt and covert battles fought in the region for centuries. The title of the book was borrowed from the phrase and term coined by a British intelligence officer, Captain Arthur Conolly, in the 19th century.

As mentioned earlier, Conolly’s ‘Great Game’ was played between the then Russian and British empires to control Central Asia. Brigadier Mohammed Yousuf, who headed Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence’s (ISI) Afghan desk (1983-87) during the US’ counter-Soviet operations in Afghanistan in the 1980s, called it “The Bear Trap”. He co-authored a book by the same name with Mark Adkin, a former major in the British Army. The book detailed the logistical and armed support that Pakistan was showered with by US’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in its covert war against the Soviet’s Afghanistan occupation.

For centuries, Afghanistan faced invasions and intrusions. It was a target of covert operations by empires and superpowers. The war continues

The evolving and changing strategies behind the ‘Great Game’ and ‘Bear Trap’ spawned a war between the US and USSR, mainly with Pakistan’s Peshawar as the launch pad. It enabled tens of thousands of ‘Mujahideen’ fighters to cross the Khyber Pass, and enter Afghanistan. With the CIA’s blessings, Pakistan was involved in a purportedly covert ‘Holy War’ against the Russian forces that occupied its neighbour.

Not all the Afghan leaders supported the Pak-bred fighters, who were mostly Pashtuns. The Tajik warlord, Ahmad Shah Massoud, who later would be President Burhanuddin Rabbani’s defence minister, was one of them. The cunning commander that he was, his militia kept the Pak-backed fighters outside Kabul. He was assassinated on September 9, 2001, or just two days before the dreadful 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US by the now-dead Osama bin Laden. Rabbani, who was the President between 1992 and 2001, was assassinated a decade later.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the war machine turned into a Frankenstein’s monster. The “Mujahids” controlled the Afghan border, from Peshawar to Quetta, and beyond. Even the Pakistan security forces feared to enter this region. Later, a new breed of fighters, called the Taliban, evolved to forge ties with Osama bin Laden’s terrorist outfit, Al Qaeda. With the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the US lost interest in Afghanistan. But 9/11 made Uncle Sam march back into Afghanistan.

India tried to rework its relations with Afghanistan through SAARC, and $3 billion investments in dams, roads, power, schools and hospitals

The US-led forces removed the Taliban from power in 2001, but the militia took to regrouping itself. Thus, when the Taliban was ousted from power, Northern Pakistan, particularly the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, turned into a haven for its members, and those of numerous other Islamic extremist groups. Now, with the US troops going back home, the resurgence and re-rise of Taliban, and the formation of two ‘Quads’ in the region, Afghanistan is caught in a new, evolving geopolitical vortex. India is caught in it, as it was earlier.

The power shift cannot be ignored. The change came after a rearmed and resurgent Taliban set out on another offensive soon after talks of US-NATO forces’ withdrawal began. The result: the return of the Taliban in Kabul.

While some specialists believe that India does not have a clear policy regarding Afghanistan, others prefer to term it as strategic patience. However, from time to time, India tried to rework and re-strategise its relations with the neighbour. India has reached out to the successive governments in Kabul. The New Delhi chapter of the 14th Summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 2007 saw Afghanistan being represented by President Hamid Karzai. Afghanistan became a regular member of the association, along with Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

India provided financial and technical assistance in several infrastructure and other projects, including a new Parliament building in Kabul. In over two decades, India poured in $3 billion investments in dams, road and power infrastructure, schools, and hospitals. This was a blueprint to use soft financial power to wield influence in the region, as opposed to the hard military presence.

New Delhi involved itself in several other exercises to ensure that Afghanistan does not turn into a neighbour-too-far, i.e. closer to Islamabad and Beijing, and hostile to India’s interests. Early this year, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval led a delegation that held talks with the Afghan leadership just before the new Biden-Harris administration assumed power in the US. Apart from his security counterpart, Doval met President Ashraf Ghani and Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, Abdullah Abdullah. However, some experts contend that this was not fruitful as those in power in Kabul did not have control across the entire country.

India has held talks with the Taliban. But New Delhi has only accepted that it is in touch with the various stakeholders to pursue its own long-term commitment

Perhaps, according to Qatar’s Special Envoy for Counterterrorism and Mediation of Conflict Resolution, Mutlaq bin Majed Al Qahtani, this is the reason that the Indian officials visited Doha to establish contact with the Taliban. He stated this while addressing a web-based academic conference on June 21, 2021, hinting that India may recognise the recent rising influence of the Taliban in Afghanistan. Clarifying that he was participating in an informal discussion, “Looking towards Peace in Afghanistan after the US-NATO Withdrawal”, in a personal capacity, he said, “I understand that there has been a quiet visit by the Indian officials to speak with the Taliban.” He added, “Taliban is a key component, or should be, or is going to be a key component, of the future Afghanistan.” In his view, this was the compelling reason for the dialogue to reach out to all the parties in Afghanistan. He was right. Now, the Taliban is in Kabul.

Earlier, Kabul’s regime was engaged in a fierce battle with the Taliban and Qahtani’s statement came days after India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s two stopovers in two weeks in Doha. While India did not officially react to Qahtani’s analysis, the Ministry of External Affairs earlier stated that India was in touch with the various stakeholders to pursue its long-term commitment to development and reconstruction in Afghanistan.

The Taliban started gaining ground even as US troops vacated the key base at the Bagram airfield, about 70 km north of Kabul, and initiated a complete withdrawal of the American soldiers. It has cost the US military 2,312 lives and $816 billion, according to the country’s Department of Defense, to wage the war in Afghanistan in post-9/11 military strategies. A Taliban spokesman then welcomed the exit of the “foreign forces” from the Bagram airfield.

Whoever controls this vital airbase enjoys a military edge. The airfield was an important base for the CIA in the anti-Soviet operations. Various chroniclers of the period of USSR occupation have dubbed William Joseph Casey, CIA Director (1981 to 1987), as the architect of the then US covert operations. He was supported by Hamid Gul, who swiftly rose through the ranks to become the Director General of Pakistan’s ISI (1987-1989). He took these secrets to the grave.

Beijing stepped up funding to Afghanistan under its expansive Belt and Road Initiative. In return, it wants the Taliban not to support demands for a separate Uighur state in China

During his recent visit to Delhi, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken agreed that there was no military solution to the conflict that afflicts Afghanistan. India’s Jaishankar said that the independence and sovereignty of Afghanistan could only be ensured “if it is free from malign influences”. The reference is to Pakistan’s involvement.

Statements stemming from Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan have complicated the situation. In a recent interview with PBS, he said that Taliban were “normal civilians”. In 2020, Khan called Osama bin Laden a “martyr”. While addressing Parliament, he referred to the mastermind of the 9/11 terror attacks in 2001, as a “shaheed”. His foreign minister, Shah Mahmood Qureshi, told an Afghanistan-based TV news channel that “he (Prime Minister Khan) was quoted out of context. A section of the media played it up”. When the interviewer prodded: “Is he (Osama bin Laden) a martyr? You disagree (with Khan)? Osama bin Laden?” Qureshi’s answer after a long pause was: “I’ll… (pause) …let that pass….” The flutter and anxiety was obvious.

As indicated earlier, China’s growing activity in the region is another significant factor that drives India’s increasing interest in Afghanistan. While China’s expansive and extensive Belt and Road Initiative in Asia originally did not include Afghanistan, Beijing has stepped up the funding in the country, and started taking an active interest.

A visit by a Taliban delegation to China late July underlined the Red Dragon’s increasing push. China expressed hopes that the Taliban would check the activities of the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement. According to a report of the UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, this group is primarily aligned with Al Qaeda and remains active in Badakhshan, Faryab, Kabul and Nuristan Province of Afghanistan. “Many Member States assess that it seeks to establish a Uighur state in Xinjiang, China, and towards that goal, facilitates the movement of fighters from Afghanistan to China,” stated the report.

On 28 July, Taliban spokesperson Mohammed Naeem posted a series of tweets. The first read, “Mullah Baradar Akhund, Deputy Political Director and Head of Political Office, led a nine-member high-level delegation and paid a two-day visit to China on 27/7/2021 at the official invitation of China”. This was followed by: “During the visit, separate meetings were held with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Deputy Foreign Minister and China’s Special Representative for Afghanistan…” Then there was an assurance: “Discussions and exchanges took place on the current situation in Afghanistan and the peace process. The Islamic Emirate assured China that Afghanistan’s soil would not be used against any country’s security.” He added: “China will continue its cooperation with the Afghan people and promised development and said that they are not interfering in Afghanistan’s affairs, but helping to solve problems and bring peace.”

However, there is a belief in certain quarters that the Taliban may not be the only actors in Afghanistan. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a platform for various militant organisations based at the Pakistan-Afghan border, enjoys clout. The TTP is an extreme rightist, radical, and trigger-happy group. The TTP possibly spearheaded the current forays into Afghanistan, and helped in laying siege to Kabul. The Afghan air force was bombing Taliban hideouts, and the army vainly resisted the advance.

India needs to deal not only with the Taliban, but also the TTP based in Pakistan. Hence, patience and calculations will help New Delhi deal with Beijing and Islamabad

Kabul was also trying to clamp down on Taliban propaganda. Four journalists were taken into custody on 26 July for visiting a Taliban-held border town, and accused of spreading enemy “propaganda”. The arrest came two weeks after an Indian photojournalist was killed while covering the fighting in Spin Boldak.

It will be a miracle if India can open a line of communication with the TTP. Along with the Haqqani Group, which was responsible for the attack on the Indian Embassy in Kabul in 2008 and operates mainly out of Pakistan, the TTP has reservations about India. But in this round of the “Great Game”, and the resultant “Bear Trap”, the nation that manages shrewd moves with patience and calculations can checkmate the other players. But this will be for a short period. Over centuries, the situation in Afghanistan has remained fluid – and fast-changing.

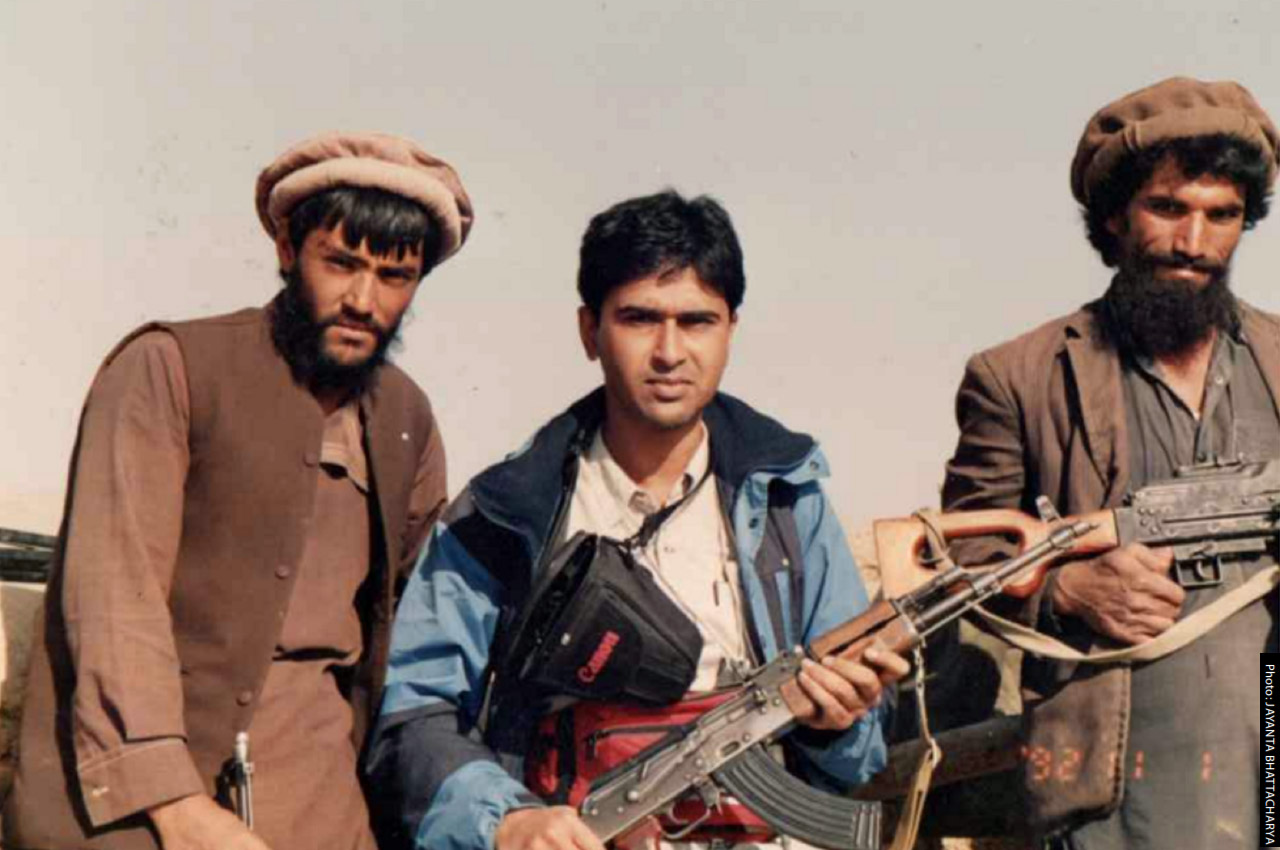

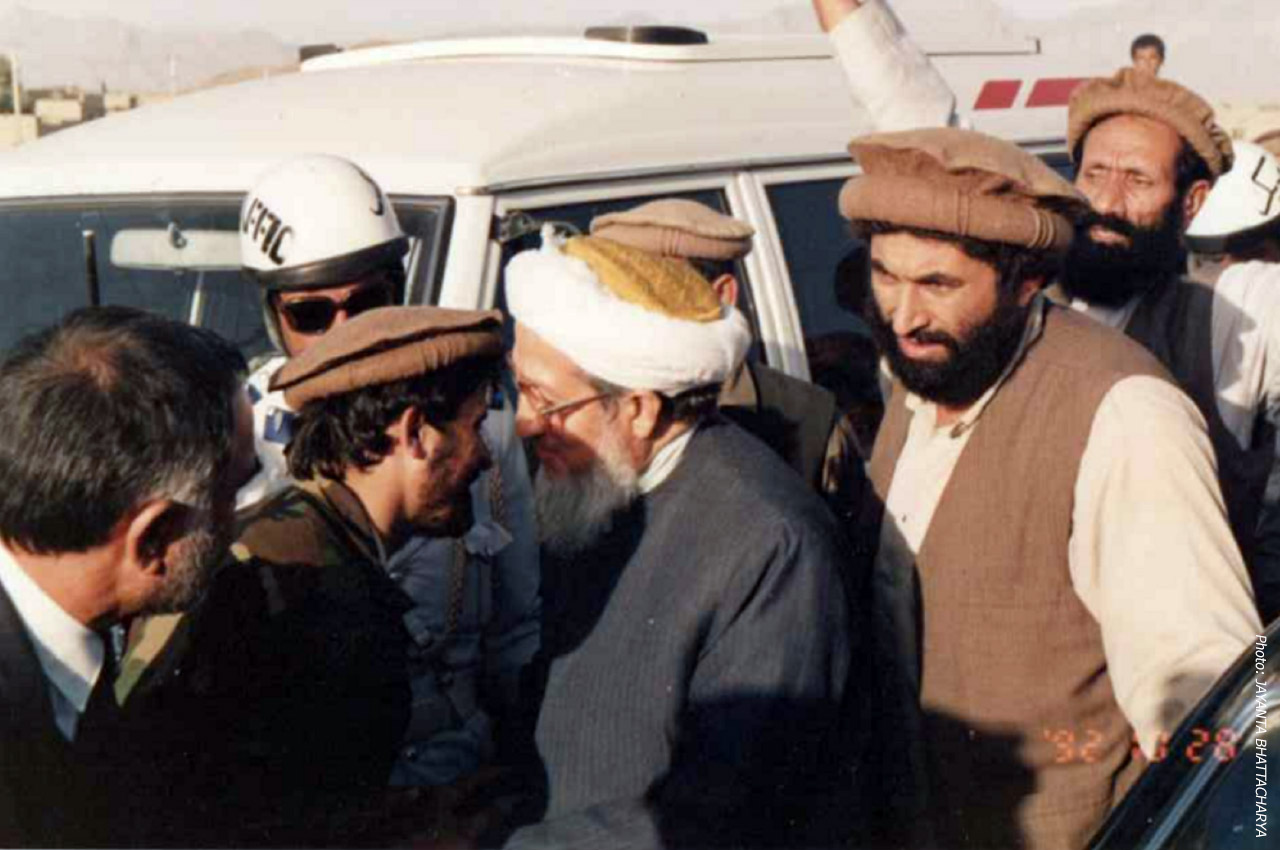

The writer has covered India, South and Central Asia, and the conflicts in Afghanistan for several decades