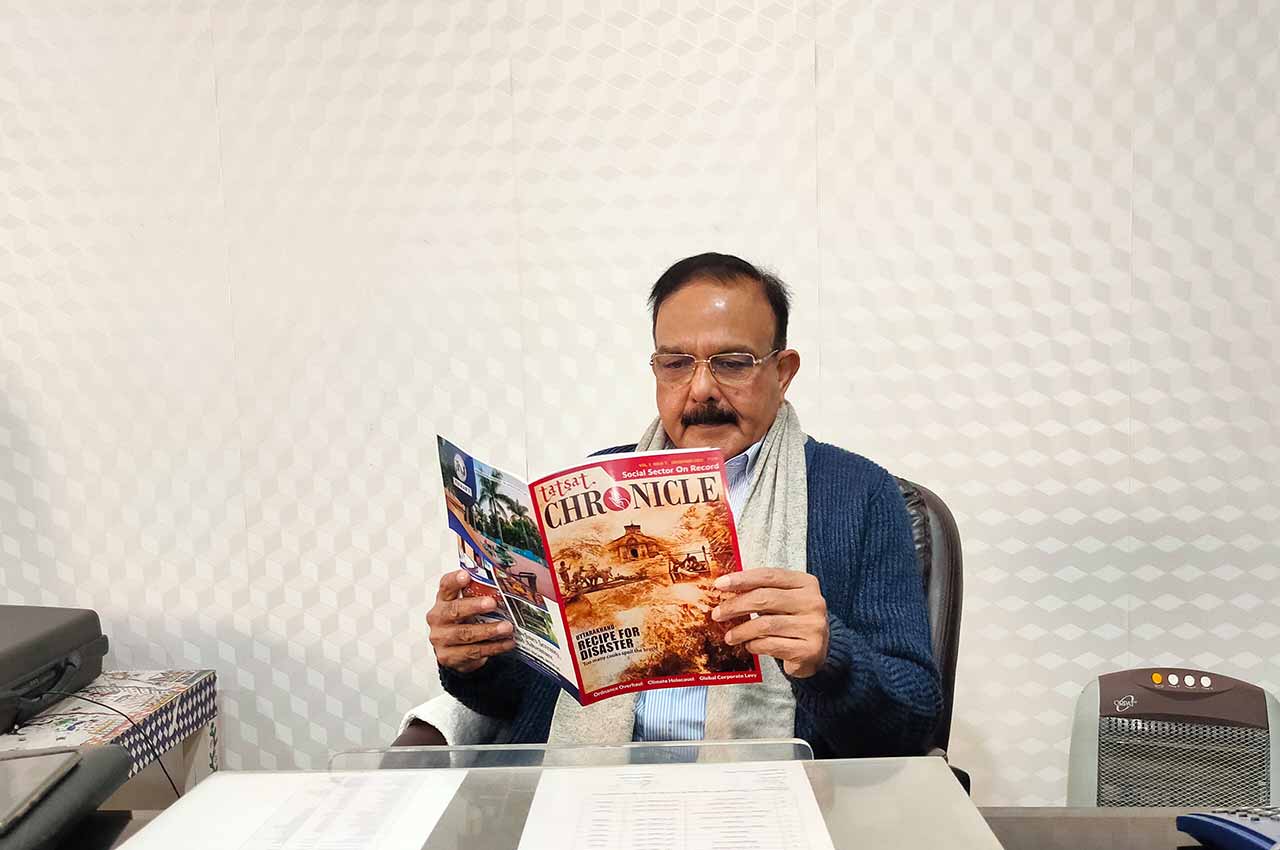

Noted social activist, former IPS officer and NITI Aayog CSO Committee member Amod Kanth, in an exclusive interview with Tatsat Chronicle, encapsulates the oversights, handicaps and pressures India faces when it comes to child rights. Excerpts:

‘Juvenile term is an imported expression’

In India, there is a general impression that juvenile crimes are increasing and are a threat to society. First, I must say that the number of children who commit crimes and the number of crimes they commit are nothing compared to such crimes reported in many Western countries we think and talk about. About 35,000 to 40,000 juvenile crimes are committed in India. This is nothing compared to the total number of crimes India reports, at 1-2 percent. So, children up to the age of 18 years, who are said to be juveniles, commit one percent of crimes. While it is not such a big deal, it does create a problem and is a serious issue.

Second, most people do not understand the term ‘juvenile’. The term is a loaded, imported expression, where a child is considered to be an adversary, someone who does something wrong or comes in contact with the law. However, our law is very different from this.