YAMUNA: DELHI’S LIFELINE IN PERIL:

The Yamuna River is not merely a geographical feature of Delhi; it is the very foundation upon which the city was established, both physically and culturally. Yamuna is the reason why Delhi was born. It nourished it. Defined it. But today – it has ceased to exist downstream of Wazirabad. For decades the river remains dead for three-quarters of the year, showing some signs of life only during the monsoon months. The big question that arises is – ‘Can Delhi survive if Yamuna dies?’.

Over the past three decades, more than ₹8,000 crores have been allocated to rejuvenate the Yamuna under various initiatives, including the Yamuna Action Plan. However, these efforts have yielded limited success. A 2017 Supreme Court observation highlighted that, despite spending over ₹1,000 crores, the river’s condition had worsened, not improved.

Ritual noises are made every year, and authorities announce their resolve to rid the river of its pollution load; but the action is confined only to the 52-km stretch of the Yamuna passing through Delhi. Experts state that, this alone is unlikely to solve the problem, for the simple reason – it is not the main problem. The primary issue lies in fact that Yamuna has been deprived of its virgin flow, vital to maintain its natural flow, whilst most authorities choose to remain silent on the issue.

The river’s health is inextricably linked to Delhi’s future, and its demise would pose an existential threat to the capital.

1994 WATER SHARING MOU:

This situation was brought about by a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by four states (Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan), in 1994, to share the waters of the Yamuna and end the constant bickering between themselves. The MOU divided the entire waters of the river of 12 billion cubic metres (BCM) between the five states (joined by Uttarakhand in 2001). Volume of water left for the natural flow of the Yamuna was only 10 cumecs (352 cusecs) and that too depended on the future completion of storage projects in the hilly regions.

In an article in 2020 written for South Asia Network for Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP),Yamuna activist Manoj Misra, a former Indian Forest Service Officer, put the MOU in plain terms, said, “In simple language, the entire surface flow in river Yamuna was distributed amongst the various claimant states, with a lament that some flow during monsoon would still be left in the river, it being un-utilisable (sic)…. One wonders if the framers of the MoU had any understanding of the meaning of ecological needs of River Yamuna”.

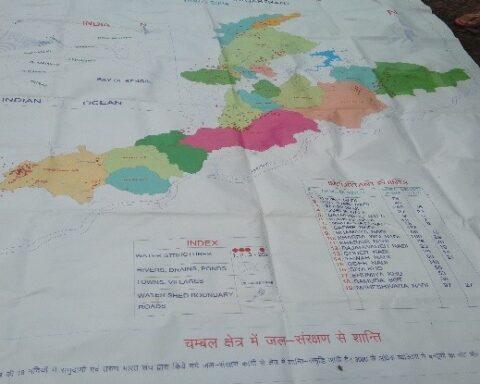

The Yamuna traverses the first 172 km of its 1376-km journey from Yamunotri without encountering any barrage or hydro-electric project till Dakpathar in Dehra Dun district near Kalsi. At this stage it is joined by the tributaries Tons, Giri and Asan, before the barrage of HathniKund in Yamunanagar (Jagadhari) is reached, about 50 km downstream. From here almost all the waters of the river are channelised into two canals – Eastern Yamuna Canal and Western Yamuna Canal leaving virtually no freshwater flow in the river till Hamirpur in Uttar Pradesh, about 700 km further downstream. Here it is joined by the Chambal which brings fresh water. The two canals carry water for irrigation to Haryana and Uttar Pradesh while a third dedicated canal – the Munak Canal carries drinking water for Delhi.

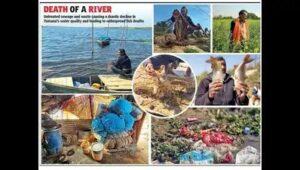

The only water that flows in the Yamuna between Hathnikund and Hamirpur are the wastewater drains that fall into it in Yamunanagar, Karnal, Panipat and Sonipat; while in Delhi as many as 18 major drains discharge domestic and industrial wastewater that flows in the name of the river. Considerable volumes of wastewater and sewage are untreated. It is not surprising that the river, considered holy by Indians resembles a drain itself these days.

With the near death of the Yamuna, fish and wildlife dependent on the river have disappeared and with it – livelihoods of fishing villages. With most of its waters diverted for irrigation, drinking water and industrial purposes, Yamuna does not have the fresh water to support the variety of aquatic and other life that it once did along its longish course. The river also performs the vital function of recharging the ground water all along.

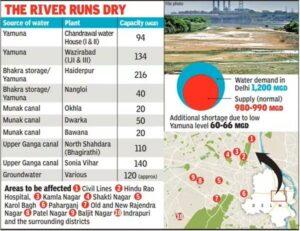

DELHI DEPENDS UPON WATER FROM GANGA, DAMS-BHAKRA AND TEHRI:

Officialdom seems to be suffering from the ‘business as usual syndrome’, little realizing the gravity of the situation. Due to water shortage in Yamuna, Delhi must depend upon waters from the Ganga and the Bhakra and Tehri Dams for its supply of fresh water. Huge investments have been made to transfer water through pipelines, yet the essential need to maintain adequate freshwater supplies within the rivers is often overlooked. Experts suggest that to preserve a river’s ecological health, only 30–40% of its annual flow should be extracted.

The strangest thing however is that even this alarming future has failed to move the authorities who have been dragging their feet for decades instead of taking urgent steps to revive the river. Though Parliament passed a law to prevent water pollution as long back as 1974, it took a couple of decades more before spotlight was focused on the highly polluted state of Yamuna, a principal tributary of The Ganga. The spotlight has been focussed on the problems with the Yamuna since 1992 when a PIL was filed in the Supreme Court. Two years later came an article titled ‘And Quiet Flows the Maily Yamuna’ which was taken up by the Supreme Court as a PIL Suo Motu.

Twenty-three years later the Court handed over the entire matter of Yamuna to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in frustration at the dilatory behaviour of the administration, observing that “zero result” had been achieved though over Rs. 1000 crore had been spent. For its part the NGT too had observed that, “the authorities lacked requisite will to execute the orders, plans and schemes sincerely and effectively which has resulted in turning the Yamuna …. into a drain carrying sewage…”.

YAMUNA- A RIVER IN CRISIS:

In the meantime, the long-suffering water-starved residents of Delhi have been regularly queueing up for drinking water summer after summer, getting most of their supplies from ground water. This has led to an alarming fall in the water table in the capital due to overuse of ground water to meet the shortfalls in supply.

Authorities and experts alike either are clueless about what ails the Yamuna’s or are simply feigning ignorance about the real cause, leave alone setting things right. However, a twist in the tale occurred in the spring of 2020 when lockdown was imposed in the wake of the Covid19 Pandemic. A few days into the lockdown (imposed on March 24) the public noticed that the Yamuna had become very clean on its own, unusual for the start of summer, the leanest period of the year.

The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) could not brush aside the photographs and videos of a ‘clean Yamuna’ that had gone viral on social media, a thing that the authorities had been unable to achieve even after scrubbing the river for years and setting up sewage treatment systems. Accordingly, CPCB deputed a team to check whether the Yamuna had indeed become cleaner, as was claimed on social media.

NATURE ACHIEVES IN 13 DAYS WHAT AUTHORITIES FAILED TO DO IN TWO DECADES’ – CPCB ANALYSIS

A two-member team led by a CPCB scientist went down to the Yamuna and collected water samples to test the water quality, from three critical points –Palla village, the entry point of the Yamuna in Delhi, Nizamuddin Bridge (35.5 km downstream) and Okhla Barrage (further 7.5 km downstream), on April 6, 2020.

After analysing and comparing the water samples with data from pre-lockdown period, the team confirmed the public perception. The Yamuna water quality had indeed been an improved. A glance at the data showed that nature had achieved within just 13 days what authorities had failed to do even after huffing and puffing for more than two decades. The comparison was based on various scientific criteria used for measuring water pollution like pH value (acidity-alkalinity), biological and chemical oxygen demand (BOD and COD), electrical conductivity (EC) and dissolved oxygen.

Though the CPCB report confirmed the general impression, one vital question remained – how had the Yamuna had become cleaner? The answer was crucial for it could provide a clue about what the authorities had neglected to do so far. The report attributed the “considerable” improvement in water quality mainly to two factors:

- he release of unusually large quantities of fresh water into the river from Wazirabad Barrage due to “unexpected and unseasonal rain” in the upstream catchment areas, and,

- No discharge of harmful industrial waste – in last week of March and the first week of April. Dilution of the river by this excess water was responsible for the improvement in its quality after lockdown. This even though just under 3000 million litres per day (MLD) of treated and untreated domestic continued to be released into the Yamuna as usual.

RIVER YAMUNA CEASES TO EXIST DOWNSTREAM OF WAZIRABAD:

The CPCB report, however made the disturbing admission that Yamuna ceases to exist after the Wazirabad Barrage since no fresh water is allowed to flow downstream from this point except during the Monsoons. It said: “River Yamuna enters Delhi at village Palla, traverses 22 km to Wazirabad Barrage where entire water is impounded to meet drinking water requirement of Delhi. River Yamuna ceases to exist downstream of Wazirabad Barrage during major part of the year and gets its flow from Najafgarh Drain at Wazirabad downstream.” In other words, most of what passes off as the Yamuna in Delhi is nothing more than a mixture of untreated domestic sewage and industrial effluents.

The Yamuna Monitoring Committee of the NGT, on receiving this information observed that for improvement in water quality, availability of fresh water in significant quantities is of importance. This naturally led Mr. Manoj Misra, to pose the question: where had the river’s natural flow disappeared?

CASE OF YAMUNA’S MISSING WATER:

The case of missing water was first uncovered by a PIL filed in the Supreme Court of India, in 1992 by Commander Sinha who sought two things – enforcement of measures to stop the pollution in the river Yamuna in Delhi and orders to permit fair levels of water flow in the rivers Ganga and Yamuna that had been severely curtailed depriving millions of people in downstream areas of the benefits of these rivers. Wildlife and fish had been killed and been deprived of fresh water that once flowed in these rivers. One of the key contentions of this case was that ‘the Central Govt has no right to approve plans that kills Yamuna River for nine months in the year by virtually stopping its flow….’

Justice Mahinder Narain’s 1996 minority judgment in the case Baldev Singh Dhillon & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors., emphasized the necessity of restoring the Yamuna River’s freshwater flow before undertaking any channelization plans in Delhi. He observed that the river was only allowed to flow freely during the rainy season, when Haryana’s canals couldn’t accommodate the increased water volume. Justice Narain argued that improving the water quality for Delhi would require increasing the supply of clean water into the Yamuna. This approach would naturally dilute pollutants and enhance the river’s ecological health. He cautioned that proceeding with development projects along the river without first addressing pollution would be detrimental, potentially transforming the river into a source of disease rather than recreation.

Bhim Singh Rawat, Associate Coordinator of the non-profit South Asian Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), said that though it is true that under the MOU 10 cumecs would be allowed for the flow of the Yamuna but that was a future plan contingent upon the completion of completion of three upstream storages-cum-dams – Kishau and Lakhwar (Tons River), Renuka (Giri River) and agreed upon in the MOU was not being maintained simply. Besides, Rawat alleged that even the 352 cusecs agreed to be released from the Hathnikund Barrage is not being released, though Haryana contradicts it. He said that the actual situation on the ground cannot be checked out since real time monitoring site Platform for Real-time Analysis of Yamuna and Ganga (PRAYAG), launched by the Jal Shakti Ministry in April 2023, is still not fully operational.

Manoj Misra aptly stated in 2022, “Natural flow in the Yamuna is its existential right. Using some part of it for us can at best be a gift and no more.” This sentiment encapsulates the urgent need for a paradigm shift in water management—from exploitation to conservation—to restore the Yamuna to its rightful state as a living river.

CONCLUSION:

The Hathnikund Barrage in Haryana diverts majority of Yamuna’s water into the Western and Eastern Yamuna Canals, primarily for irrigation and drinking purposes. Consequently, the riverbed between Hathnikund and Wazirabad often runs dry, with the river’s flow reduced to a trickle or completely absent during non-monsoon months. Downstream, the river carries untreated sewage and industrial effluents, exacerbating its pollution crisis.

Yamuna’s survival hinges on coordinated efforts between governments of five states, central government, environmental organizations, and the public, ensuring two factors- increase in freshwater flow and reduction in pollution. Only through collective action can the river be restored to its rightful place as a vital and sacred waterway.