IN January this year, India’s drug regulatory authority, the Drugs Controller General of India, granted emergency use clearance to the locally produced coronavirus vaccine, Covaxin, manufactured by the Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech. The clearance was granted even as the third stage of the trial—which involved testing on 25,800 participants across 25 sites for efficacy and safety—was still underway. Clinical trial laws in India allow accelerated authorization for drugs after the second phase of trials, for “unmet medical needs of serious and life-threatening diseases”.

As of May 1, as the second wave of the pandemic raged across the length and breadth of India, Bharat Biotech was yet to publish the full data set of its third phase “clinical trial mode” for peer review. However, on March 3, the vaccine manufacturer issued a three-page press release in which it claimed that Covaxin delivered 81 percent efficacy, based on data gleaned from a mere 43 cases. “The first interim analysis is based on 43 cases, of which 36 cases of Covid-19 were observed in the placebo group versus 7 cases observed in the BBV152 (Covaxin) group, resulting in a point estimate of vaccine efficacy of 80.6%,” said the press note.

By February, health bulletins issued by various countries, including India, warned that even those fully vaccinated would need to maintain Covid-19 protocol– physical distancing, mask-wearing and hand hygiene. These bulletins highlighted that the vaccines prevent serious illness and death but do not offer protection from infection, especially since the virus is mutating fast and new strains are being discovered. On April 19, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who had taken both doses of Covaxin, tested positive for Covid-19 and was admitted to the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi.

The discussion over the efficacy of vaccination in controlling the pandemic continues. There is relatively less interest in the treatment of the infected, even though treatment seems an effective option as the virus does not pose a grave risk to life in asymptomatic cases or for people who evidence mild symptoms.

In the normal course, vaccine development takes place over 10 years and at high cost. Vaccine development is especially prone to failure, with only six percent making it to the market, according to a study published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in the US. For example, research for developing an HIV vaccine began in 1984, but the world is nowhere closer to getting one despite spending billions of dollars in these 37 years. In the case of Covid-19, vaccines were given emergency use approval in the US, Europe and India, fast-tracking their entry into the market.

By April, the payout to shareholders by vaccine manufacturers had reached a whopping $26 billion, showing just how much money rides on vaccination. In India, Adar Poonawalla, CEO of Serum Institute of India (SII), the manufacturer of Covishield vaccine developed by AstraZeneca-Oxford, said in an interview to NDTV that he was making profits by selling the vaccine to the central government for ₹150, although he had sacrificed “super-profits”.

State of Clinical Trials in India

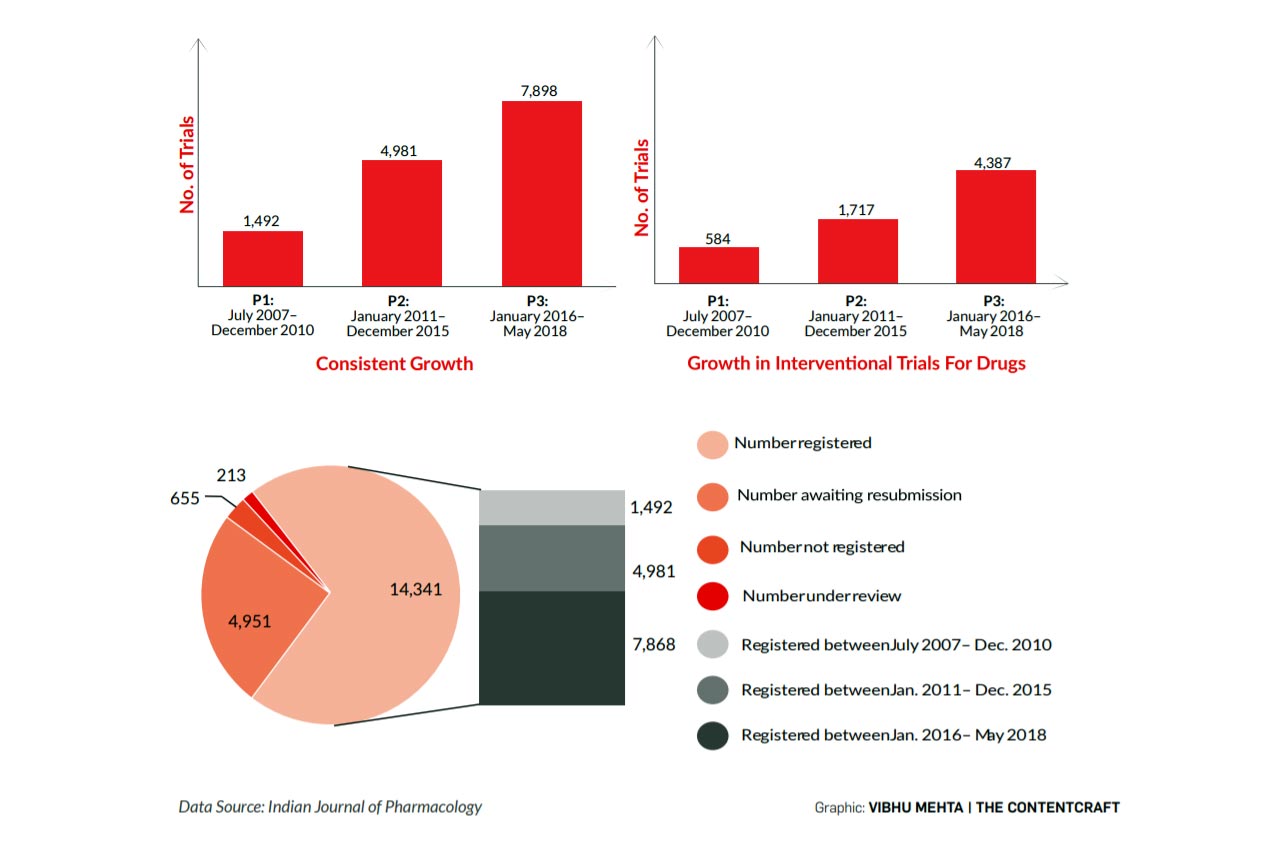

According to data available in the public domain, in 2020 alone, since the outbreak of the pandemic, 477 Covid-19 clinical trials took place in India that were registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI). However, the outcome of these trials is not publicly available. A decadal study (July 2007-May 2018) published in the Indian Journal of Pharmacology in May 2020 reveals an exponential growth in clinical trials in India, making it even more compelling for the Government of India to ensure greater transparency

NOW, there seems a general consensus among epidemiologists, health experts, and governments that the best way to control this pandemic is to vaccinate a sizeable chunk of the population. One estimate suggests that over 60 crore (600 million) Indians must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, while other estimates peg the figure at 90 crore (900 million). In other words, to achieve herd immunity, India needs to administer anything between 120 crore (1.2 billion) to 180 crore (1.8 billion) doses of two-shot vaccines.

By February, health bulletins issued by various countries, including India, warned that even those fully vaccinated would need to maintain Covid-19 protocol—physical distancing, mask wearing and hand hygiene. These bulletins highlighted that the vaccines prevent serious illness and death but do not offer protection from infection, especially since the virus is mutating fast and new strains are being discovered

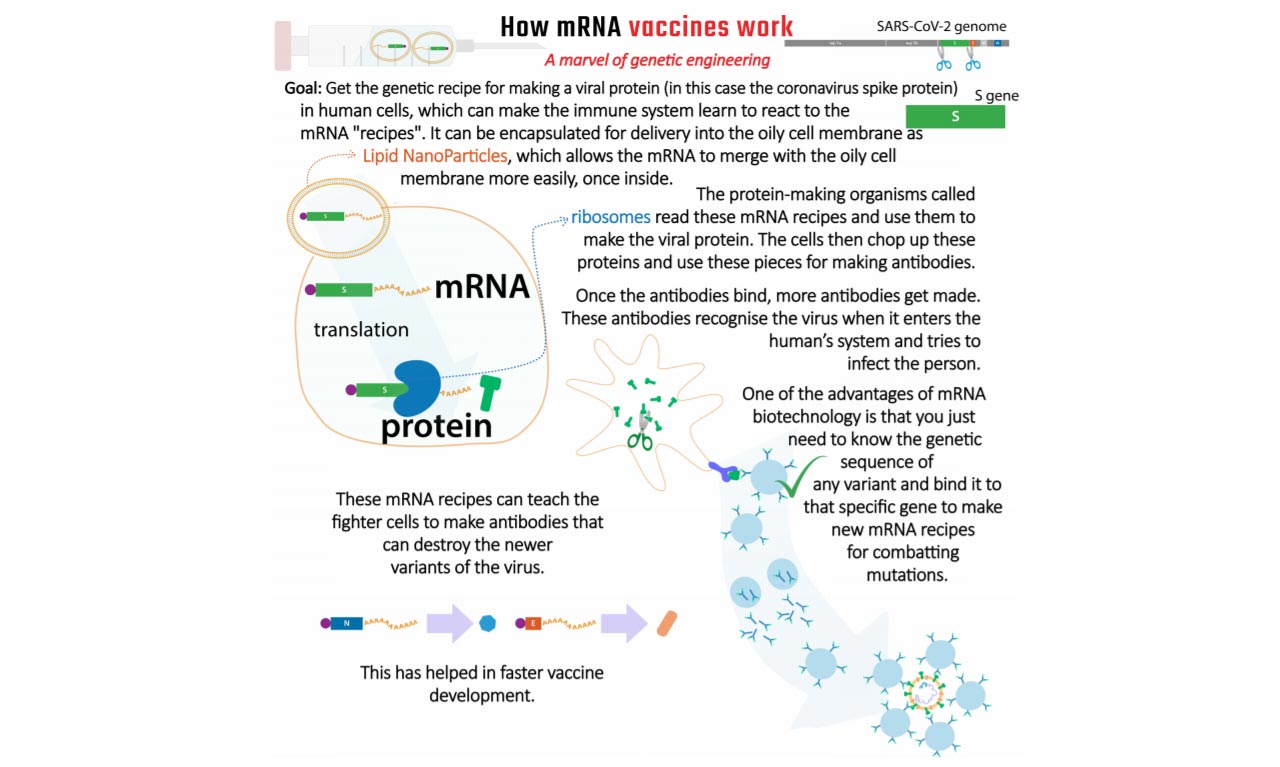

Some experts have questioned whether this is indeed the best course of action with new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerging due to mutation. The Lancet COVID-19 Commission India Task Force published a report in April, flagging this particular concern. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use messenger RNA (mRNA), a technology never tried before in human vaccination.

At a time when the Government of India seems preoccupied with political calculations rather than health concerns, and when the Centre has shown a penchant for fobbing off responsibility for vaccine provision to the state governments after announcing that all adults can now be vaccinated, and has left it to the states to buy vaccines directly from manufacturers “in the open market at a pre-declared price”, it is apt to focus on medical interventions and clinical drug trials that have caused pain and suffering to the poor in the Third World.

Fighting opacity: Experts demand greater transparency and more disclosure from the government

In 2020, Indian regulatory authorities greenlighted the repurposing of several existing drugs for treating patients suffering from Covid-19, alarming many noted health experts. They expressed serious concerns about the manner in which these drugs were repurposed without adequate scientific data to back claims of efficacy in treating Covid-19. Health experts have been long demanding greater transparency and accountability by making clinical trial data widely and publicly available. In August 2020, Dinesh Thakur and 11 other health experts and civil society activists sent a hard-hitting 13-page petition to Union Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan, demanding more stringent application of rules and greater accessibility to critical information based on which Indian regulators grant approval to drugs. Some of the key concerns raised by the experts in the petition were:

- Make available more information to the public regarding the workings of the Indian drug

regulatory system. - Clinical trial data and the final outcome must be declared through the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI).

- Decision and file notings for applications for approval of new drugs by the DCGI must be put in the public domain.

- Inspection reports by Drug Inspectors and lab test results must be accessible to the public.

- Minutes of meetings of the Ethics Committee, pre-clinical data filed as part of the application to DCGI to conduct clinical trials, and the reasons for the decision taken by the DCGI for granting approval or rejection be made public through CTRI.

- Disclosure of primary data for all clinical trials and not just those sponsored by the Indian Council for Medical Research as per guidelines set by “The Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human

Subjects”. - Enforce the legal obligation of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) to disclose regulatory data in the form of a searchable database.

- Make public all records pertaining to new drug approvals, including deliberations, internal memos, and file notings made by the Subject Expert Committee for granting approval.

- The Ministry of Health must take steps to create a publicly accessible searchable online national database that contains all necessary information on manufacturing and loan licences, all inspection reports and all bioequivalence and stability data.

- Reports of tests conducted by the Central Drug Laboratory and State Drug Laboratories must be published suo motu in a searchable national database.

- CDSCO must create a digital database to disseminate all enforcement actions (civil or criminal) at all levels of drugs regulation.

- Indian Pharmacopeia, published by the Indian Pharmacopeia Commission (IPC), be made publicly available without charge on its website because of the manner in which Section 4 of the RTI Act has been interpreted by the Chief Information Commissioner and the Delhi High Court in previous litigation.

Publicly available records provide substantial evidence of how people in India, and other parts of the world, have been enlisted for participation in clinical trials without being fully informed of the risks or possible consequences. In 2010, during the course of academic research, Susan Reverby of Wellesley College, US, discovered documents that showed that over a thousand people in Guatemala had been deliberately infected with syphilis as part of a research project in the 1940s. The US, worried that its soldiers would return with the infection after World War II, was studying whether penicillin would prevent the disease and could be administered as a prophylactic. “Unless the law winks occasionally, you have no progress in medicine,” wrote Thomas Rivers, who headed the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research, in his memoir in 1967. He led the research team in Guatemala. Among those on whom this experiment was conducted were psychiatric patients who could not sign their own names, and were referred to in records by their nicknames.

In the normal course, vaccine development takes place over 10 years and at high cost. Vaccine development is especially prone to failure, with only six percent making it to the market, according to a study published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), US. For example, research for developing an HIV vaccine began in 1984, but the world is nowhere closer to getting one despite spending billions of dollars in these 37 years

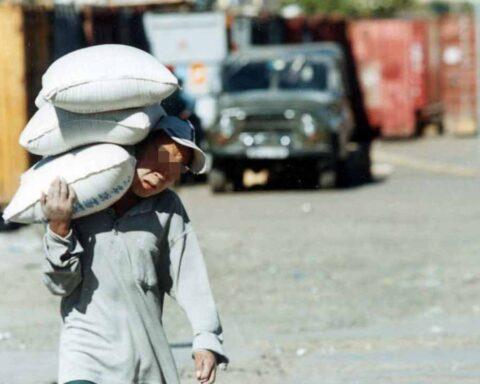

With stricter laws and higher levels of literacy in the West, large pharmaceutical firms look for less literate societies, which are naïve about medical practices–Africa has long suffered from unscrupulous drug trials. India too has been the site of testing, bringing untold misery to poor and voiceless communities.

The widespread use of vaccines that were approved for emergency use has virtually turned the entire world’s population into trial candidates. India, though, has a special history of testing gone wrong that is now timely to recall. Dr Amar Jesani of the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan explained in a film produced by Wemos International, which monitors medical trials, that the cost of drug trials can be reduced by up to 75 percent by shifting to India from the West. Also, given the large population, finding subjects for trials is seldom difficult in India. Laws exist but are not implemented, which paves the way for those seeking to conduct drug trials in India.

He further explained that trials are necessary as part of scientific research to combat new diseases and find new ways of combatting old diseases. Yet, no human rights should be violated in such trials, and only drugs relevant to the population should be tried on them. If a trial is successful, the poorer nations should have access to the drug at a reasonable price.

Studies were conducted between 1998 and 2015 on 3.75 lakh women in Mumbai’s slums, villages in Osmanabad district of Maharashtra, and in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu, to evaluate a screening method for cervical cancer. These studies were funded by the US National Cancer Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—the researchers used a no-screening control arm, which deprived women of screening even when it was available. Such a no-screening process in a research trial usually only exists when no real screening test is available for the condition. Given that this study occurred at a time when this screening test was available, the rationale of keeping these women from screening could have meant not diagnosing the condition at a time when cancer could still be treated.

Studies were conducted between 1998 and 2015 on 3.75 lakh women in Mumbai’s slums, villages in Osmanabad district of Maharashtra, and in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu, to evaluate a screening method for cervical cancer. These studies were funded by the US National Cancer Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—the researchers used a no-screening control arm, which deprived women of screening even when it was available. Such a no-screening process in a research trial usually only exists when no real screening test is available for the condition. Given that this study occurred at a time when this screening test was available, the rationale of keeping these women from screening could have meant not diagnosing the condition at a time when cancer could still be treated.

IT is not only foreign outfits that subject India’s poor to such tests. Between 1976 and 1988, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the country’s top medical research body, conducted a test to monitor poor women with cervical lesions, to see how many of them would eventually develop cancer. Nine women developed invasive cancer and 62 had localised cancer. A responsible medical practitioner might have intervened earlier, to treat the condition rather than continue the passive monitoring of these cases.

WHAT is needed is for drug companies to be forced to proactively disclose the drugs they are running trials for, and their findings: this would at least reduce the chance of trials being conducted on populations at whom the drug is not targeted. In 2018, Glenmark conducted trials for an osteoporosis drug that would be used in elderly people with hip or knee problems. Trials, however, were conducted on young villagers who were lured with the offer of ₹500 for undergoing the trial, according to a report published in The Wire. The existing regulations do not expressly forbid granting money to trial participants—if they lose the day’s wages and pay for transport, it is fair they should be compensated. But the sum involved, even if low, might serve as an incentive to participate in such clinical trials.

Studies were conducted between 1998 and 2015 on 3.75 lakh women in Mumbai’s slums, villages in Osmanabad district of Maharashtra, and in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu, to evaluate a screening method for cervical cancer. These studies were funded by the US National Cancer Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

A Right to Information (RTI) application by an NGO, Swasthya Adhikar Manch, showed that between 2005 and 2016 there were over 24,000 cases of adverse effects from trials of drugs, including death. In November 2017, Sunday Guardian Live published a detailed report stating that over 4,500 deaths were reported during the same period, and in just 160 cases compensation was paid to the bereaved families.

Seven tribal girls were killed in 2009 during clinical trials for a vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. The girls enrolled for this trial were from Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat, and many came from tribal communities. Since they were illiterate and could not sign, the drug company recorded just their thumb impressions and did not bother to explain to them that they were part of a vaccine trial. The Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1945 does not contain any provision for punishment in case of trials posing a risk to life.

In 2019, new rules for drug trials called New Drugs and Clinical Trials Rules, 2019, were introduced, amending the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1945, under which compensation would be offered to those suffering permanent disability or death on account of such trials. The compensation amount would be decided by the Drugs Controller General of India. The new rules were meant to promote clinical trials in India, offering a time-bound review of applications and a month’s time for approval of the trial in case of a drug developed indigenously. The global clinical trial industry is estimated at over $44 billion. In 2017, it was estimated that the Indian clinical trial industry was worth $1.6 billion (about ₹9,000 crore).

INDIA is currently witnessing debate over the price of vaccines. It is pertinent to note that this is a global phenomenon, and news reports in March indicated that Pfizer was already considering hiking the price of its vaccine once the pandemic is declared over. Meanwhile, the Indian government has also stonewalled all queries regarding the management of the latest health crisis under the Right to Information. This level of opacity can prove fatal for individuals and for democracy. Such an artificially created information vacuum can prove disastrous in the mid and long terms, ultimately damaging the health of the nation.

Dinesh Thakur, who served as global head of Research and Information Portfolio Management at Ranbaxy Laboratories, once India’s largest manufacturer of generic drugs, said in an email response to a query from Tatsat Chronicle: “Transparency and accountability have not been a pressing issue with the Indian drug regulator, CDSCO. The pandemic has brought this issue into sharp focus. The way it provided emergency approval to experimental therapies like Favipiravir and Itolizumab, which eventually have proven to be ineffective last summer is questionable. Further, approvals granted to Covaxin without proper conduct of Phase III studies only exacerbated its opaque decision making. The fact that it stonewalled telling the country who all were responsible (as members of the Subject Expert Committee) for providing this approval for months tells you how opaque and unaccountable its decision-making processes are. We need to bring in transparency to force the regulator to make public its assessment and the process by which it makes such assessment of clinical studies and declares any potential conflicts of interest among its advisory committees so that the people have confidence in the decisions it makes.”

In 2019, new rules for drug trials called New Drugs and Clinical Trials Rules, 2019, were introduced, amending the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, under which compensation would be offered to those suffering permanent disability or death on account of such trials

Thakur quit Ranbaxy in 2005 after reporting malpractices to the management of the company. He then became a whistleblower, exposing how Ranbaxy was falsifying drug data and violating international norms for drug manufacture and laboratory practices. In May 2013, Ranbaxy pleaded guilty to criminal felonies and agreed to pay $500 million to resolve allegations of falsified data. Journalist Katherine Eban of The Wall Street Journal documented the deceit behind generic drug manufacturing practices in her 2019 bestseller, Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom.

Thakur quit Ranbaxy in 2005 after reporting malpractices to the management of the company. He then became a whistleblower, exposing how Ranbaxy was falsifying drug data and violating international norms for drug manufacture and laboratory practices

Given the vast sums involved, the huge clout wielded by Big Pharma, and the enormous debility and suffering that unscrupulous trials heap on the weakest and poorest, clinical trials ought to be conducted with far greater transparency. There is a need for more focused, independent research on the whole industry. Such research should feed into much-needed legislation to protect the health and well-being of the weakest.