As the world pushes for electric vehicles to contain global warming, the demand for metals like lithium, nickel and cobalt that will power the transition have exploded over the past decade. But of late serious doubts have begun to creep in about whether the benefits expected from the key transition metals used for lithium-ion storage batteries for cars and power grids will outweigh the human and environmental costs that their mining, refining and disposal impose.

Though alternative sources of electricity like wind and solar, have been in use for decades particularly in remote areas falling outside grid coverage, of late, particularly after the 2015 Paris Climate Summit asked countries to set targets, they have given rise to great hopes as the way to reduce emission of carbon dioxide—the main component of greenhouse gases by burning fossil fuels like coal and petroleum. There is much all-round optimism that the road to net-zero will be paved by renewable energy that would enable the world to meet targets and avert environmental catastrophe by the end of this century. Today, electric vehicles comprise a fraction of global car sales.

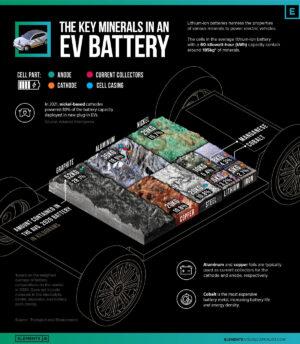

Not surprisingly, the world is witnessing feverish activity to replace petroleum-based cars with electric vehicles and coal and oil-fired power plants by solar and wind power. But the key ingredient for this transformation are rechargeable storage batteries and natural magnets, which in turn depend upon a few critical metals and minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite.

The urgency to increase the supply of renewable energy following the Paris Summit is evident from the dramatic rise in the demand for some of these metals. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in the five years between 2017 and 2022, demand for lithium tripled, demand for nickel rose by 40% and that of cobalt jumped by 70%.

A 2023 World Economic Forum (WEA) publication shows that lithium production has increased ten-fold since 1995 from 9.5 million tonnes to 106 million tonnes in 2021.

A breakup of the minerals used in an electric vehicle will give an idea about the quantities that required, for now and for the future. A 60-kWh battery pack weighs about 182 kg of which is made up of, among other things 6 kg of lithium, 8 kg of cobalt and 29 kg of nickel. According to IEA estimates, there should be about 2 billion electric passenger cars by 2050 to get to net zero. The total number of passenger cars in 2020 were 1.2 billion. That gives an idea of the enormous amounts of the three metals are going to be needed in the next few decades, unless of course new technologies are discovered for efficient energy storage, or the pressure is eased by concentrating on public transport rather than personalised vehicles.

Unfortunately, these critical metals needed to power electric vehicles are unevenly distributed around the world. Just to take the case of one of the three critical transition metals lithium, nearly all the world’s production is limited to just eight countries. Between 85% to 90% of it is concentrated in just three paces – Australia, Lithium Triangle straddling Chile, Bolivia and Argentina, and China. Seventy per cent of another of these transition metals—cobalt—is found in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while about 40% of nickel is produced by Indonesia. Though this poses problems for the supply chain, the more worrisome problems are the health and humanitarian issues surrounding their mining and disposal.

Also Read: India’s Long Road To Net-Zero

On the one hand, the environment is adversely impacted as mining can devastate the environment if done unsustainably leading to deforestation, water pollution and what is known as dewatering. It takes 2 million litres of water to extract a one tonne of lithium. On the other hand, are the serious health and humanitarian issues that surround the mining of critical transition metals and minerals.

Take the case of Kasulo, an urban neighbourhood in Kolwezi in the heart of the cobalt mining areas of Democratic Republic of Congo. A study jointly conducted by Belgian and Congolese researchers found that when cobalt ore was discovered under a house in the area, the entire neighbourhood turned into artisanal mines.

Dozens of mine pits were dug as people hunted for cobalt with little regard for safety. Children living in the mining district were found to have ten times as much cobalt in their urine than elsewhere. The situation is worsened by the fact that copper and uranium are associated metals found in the cobalt mines of Congo. Uranium is radioactive and gives out radon gas, which is carcinogenic. This has forced a number of multinational corporations to issue pledges that they will source metals from places where more responsible mining is being done.

The issue of child labour (and deaths) and child trafficking in cobalt mining as well as the conflict that has been raging in Congo and its neighbourhood was first flagged in 2016 in a report by Amnesty International. It was, however, chronicled in detail by Siddharth Kara in his 2023 book, Cobalt Red—How the Blood of Congo Powers our Life. American think tank Council for Foreign Relations (CFR) has said in an article about Congo in February that “clashes involving militant groups over territory and natural resources, extra-judicial killings by security forces, political violence and rising tensions with neighbouring Rwanda (mostly regarding its alleged support for militia groups in Congo) have contributed to the deadly conflict… Since 1996 the conflict in eastern DRC has led to the deaths of approximately six million deaths. The same article says that Rwanda and Uganda – and militias with their support – have financial stakes in Congolese mines (though they are not always legitimate).” The biggest manufacturers of electric vehicles source this metal from one of the most dangerous places on earth.

The story appears to be repeated in the case of Indonesia for another of these critical transition metals—nickel. Indonesia happens to be the world’s largest supplier of nickel. Historically, nickel has been used for the manufacture of stainless steel but now it has found importance in solar infrastructure, lithium-ion, nickel-cadmium and nickel metal hydride batteries. The Southeast Asian nation began to suffer from serious environmental as well as humanitarian issues when nickel was found in the 1990s of the last century. The regime of West-backed military dictator Suharto granted a concession to a multinational nickel company over 55000 hectares of land of which 35000 hectares fell under protected forests.

The Asian Economic Crisis of 1997-98 led to the ouster of the Suharto regime and with it the project too suffered a setback. It was revived in 2006 but an Environment and Social Impact Assessment report in 2010 by Earthworks, an American NGO said that the project was likely “to harm aquatic biodiversity in the streams, rivers and ocean for extended period of time.” Despite this, post-2015, Indonesia pushed forward with plans to mine and refine nickel through a 20-year industrial master plan with the nickel industry as its centrepiece. The industry was also declared a national strategic project that promises fast-track land acquisition, a guarantee that many say has triggered land conflict between project developers and local communities including indigenous groups.

According to Climate Rights International (CRI), the government has set up an industrial park (Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park-IWIP) in Indonesia’s Halmahera region for smelting and processing from the nearby nickel mines. Those who live close to IWIP and the mines say that the operations are a serious threat to their land rights, rights to pursue their traditional ways of life and rights to clean water, said CRI in its January, 2024 report. At least 5331 hectares of tropical rainforests have been cut within the IWIP area, the report said.

According to CRI, Tesla, Volkswagen and Ford have sourced nickel for the EV projects from Indonesia, including from projects that operate from IWIP. But EVs come at a cost to the communities, mostly in developing countries where materials are extracted from.