India had gone into a freeze at this time last year in a bid to arrest the spread of Covid-19. The lockdown was announced with just a few hours’ notice and took people by surprise. It commenced on March 25 and its most rigorous phase lasted till April 14. Thereafter, it was relaxed in stages till May 31. In all, the phase of enforced isolation lasted 68 days. Migrant workers, a vulnerable lot, were the hardest hit. The government deprived them of the means of transportation initially to restrict them to their places of work. But it had to yield and arrange trains and buses as the sight of thousands of workers with their families trudging back home hundreds of kilometres away evoked widespread attention and criticism.

One year on, as the second wave of the pandemic surges through India, it has brutally exposed the underpreparedness of the Government of India in building up capacities to contain the exponential increase in positive cases and deaths. A granular study of the data available in the public domain reveals a disturbing picture. It’s clear that the long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic will continue to haunt India for years to come. It has delivered a body-blow to the fundamental structures that underpin our way of life, society, and economy. The second wave of the pandemic also reveals the gross administrative incompetence in failing to anticipate the looming danger despite several early warnings by experts.

Migrant workers report steep decline in income

Migrant workers report steep decline in income

According to a recently-published study, 60 percent of the migrants said they returned to their native places after the lockdown because of no work. Thirty percent feared contracting the infection. Nearly 10 percent said they were short of money.

For the study, the Inferential Survey Statistics and Research Foundation (ISS&RF) interviewed 2,917 migrants who had returned to 505 gram panchayats in 34 districts of six high-migration states: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. The study was conducted telephonically in July and August 2020.

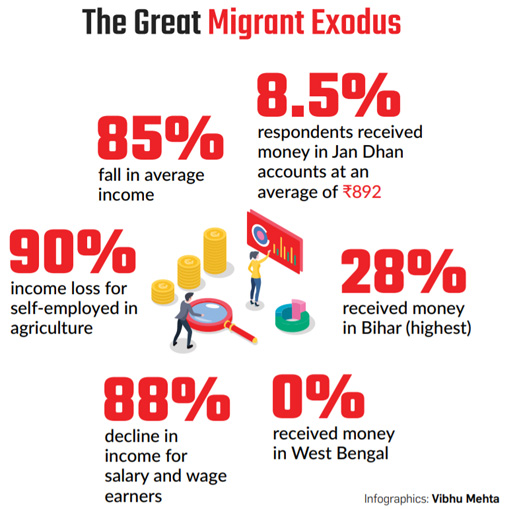

The migrants reported a fall in income on average of 85 percent. Those who were self-employed in agriculture lost 90 percent of their income upon returning to their native places. Salary and wage earners said they suffered an 88 percent decline. Those self-employed in non-agricultural activities saw an 86 percent dip. Non-agricultural casual workers lost 57 percent of their earnings and the decline in income of casual agricultural labourers was 62 percent.

Eight-and-a-half percent of the respondents admitted to getting money from the government in their Jan Dhan bank accounts. The maximum number was in Bihar – 28 percent, followed by Odisha (11 percent). In Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, five percent of the migrants got the bank transfers. None of the respondents in West Bengal said they got the dole; in Chhattisgarh the number was just 1.40 percent. On average ₹892 was transferred, the amount varying between ₹1,450 in Jharkhand and ₹518 in Odisha. Bihar’s migrants got on average ₹1,021 in their villages, those of Chhattisgarh ₹786 and of Uttar Pradesh ₹864.

In all, 68 percent said they were willing to return. Forty percent cited employment opportunities at migration destination as the reason. For 33 percent, it was employers willing to re-employ on same or higher wages that was the draw. Those citing no work at the native place as a reason for returning was 23 percent.

The authors of the study say that data on migrants should be systematically collected and digitised to formulate better action plans. Their welfare entitlements should be portable. ‘One nation, one ration card’ could help them get either free or subsidised grain or cash to buy it across the country. Portable health insurance would also save them from catastrophic medical expenses. The scope of works under MGNREGA, the rural jobs scheme, could be expanded to absorb a whole lot of skilled and unskilled migrants. The eastern states from where most of the migration happens need a massive programme of rural housing, infrastructure development and establishment of agricultural markets, the authors say, so that rural communities get better value for their produce and forced migration is stemmed.

In all, 68 percent said they were willing to return. Forty percent cited employment opportunities at migration destination as the reason

Online Classes Poor Substitute for Face-to-Face Teaching

The attempts to contain the pandemic took a toll on education as well. As schools and colleges were closed, face-to-face teaching was replaced by online classes. But digital teaching is an inadequate substitute, says the Field Research Group of the Azim Premji Foundation–based on a survey of 398 parents and 1,522 teachers across 26 districts in five states. The findings were published in September 2020 in a study called “Myths of Online Education”. They related to public schools that had more than 80,000 students between them in some of the poorest areas of the country. The study was based on telephonic discussions. It was supplemented with a few open-ended questions for teachers.

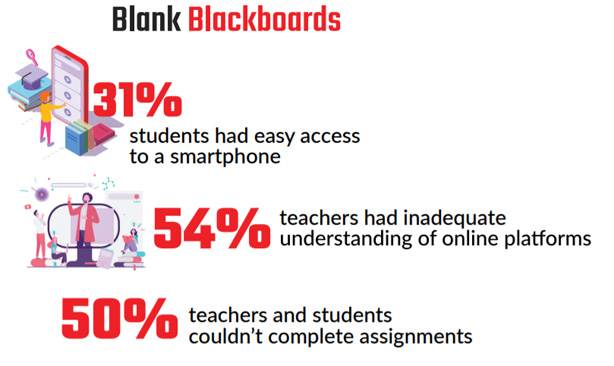

The teachers said that of the 80,088 students who attended regular classes, smartphones were easily available to 22,245 or 31 percent of them. The parents said that 87 percent of them had smartphones but only 22 percent had more than one. The parents with one phone could not spare them for use by their children.

The teachers said that of the 80,088 students who attended regular classes, smartphones were easily available to 22,245 or 31 percent of them. The parents said that 87 percent of them had smartphones but only 22 percent had more than one. The parents with one phone could not spare them for use by their children.

Apart from the affordability of devices and data charges, poor connectivity was affecting learning outcomes. One teacher said that much of the 45-minute class was spent in checking audibility. Teaching was not participative; it was mostly one-way communication with the teachers making PowerPoint presentations or playing videos. The teachers were not sure that students were grasping what was taught. They had no way of motivating those lagging behind.

Sixty-one percent of the parents said online classes were not suitable. Fifty-four percent of the teachers had inadequate knowledge of online learning platforms. Seventy-five percent of the teachers spent less than one hour a day in online classes for any grade. More than 50 percent of them said that no meaningful assessment of children’s learning was possible in online classes. Nearly half of the teachers said children were unable to complete assignments shared during online classes, which in turn led to serious gaps in learning.

Apart from affordability of devices and data charges, poor connectivity was affecting learning outcomes. One teacher said that much of the 45-minute class was spent in checking audibility

Bulging Food Stocks Come To Rescue

India’s huge stock of procured foodgrains came in handy during the lockdown and the pandemic. The government was able to give grain free to the poor and stave off hunger deaths. The impounding of grain in excess of buffer stock norms is indeed wasteful and has been criticised by economists. The cost of procuring, storing and distributing a quintal of rice is ₹3,727 – which is double the support price paid to the rice farmer, namely, ₹1,868 per quintal. There is a similar differential in the case of wheat. But without these excess stocks there would have been much suffering. Despite making grain available, a large number of people went to bed with their stomachs less than full as the pandemic and the lockdown disrupted the economy. “Economic recession worsened food insecurity,” wrote economist Jean Dreze in the Indian Express in January. Dreze championed the National Food Security Act, which the Manmohan Singh government enacted. It helped cope with the pandemic as it assures cereals at very low rates to 67 percent of the population. If rations in kind (as grains) were replaced with cash transfers as some economists had argued, the network of ration shops across the country would have withered away, leaving the poor at the mercy of profiteering private traders.

But India’s foodgrain economy suffers from a double imbalance, Dreze writes. It procures more than needed. Annual procurement of foodgrain ranged between 69 million tonnes and 86.5 million tonnes between 2017-18 and 2019-20. Annual offtake through various welfare schemes was in the range of 60 million tonnes and 66 million tonnes during this period. With protesting farmers demanding legal guarantees for assured procurement at minimum support price (MSP), procurement will continue as before. Stocks will remain high. They were 53 million tonnes as of January 1, 2021, and as high as 83.5 million tonnes in June 2020.

The procured cereals usually cannot be exported without a subsidy. The best option is to use it to relieve hunger. India’s production of foodgrain was 285 million tonnes in 2017-18 and 2018-19. In 2019-20 it was 297 million tonnes. The second Human Development Survey shows that average cereal consumption was a little below 12 kg per person per month in 2011-12. Using this benchmark, Dreze calculates that aggregate cereal consumption is likely to be around 200 million tonnes in a normal year. Sustained poverty reduction would raise it a little beyond that but not much. Rather than procuring more rice and wheat than needed, the government could use the food subsidy to promote crop diversification into millets (which are known as nutri-cereals). The production of more pulses and oilseeds would help pare the import bill.

Public Healthcare Creaking

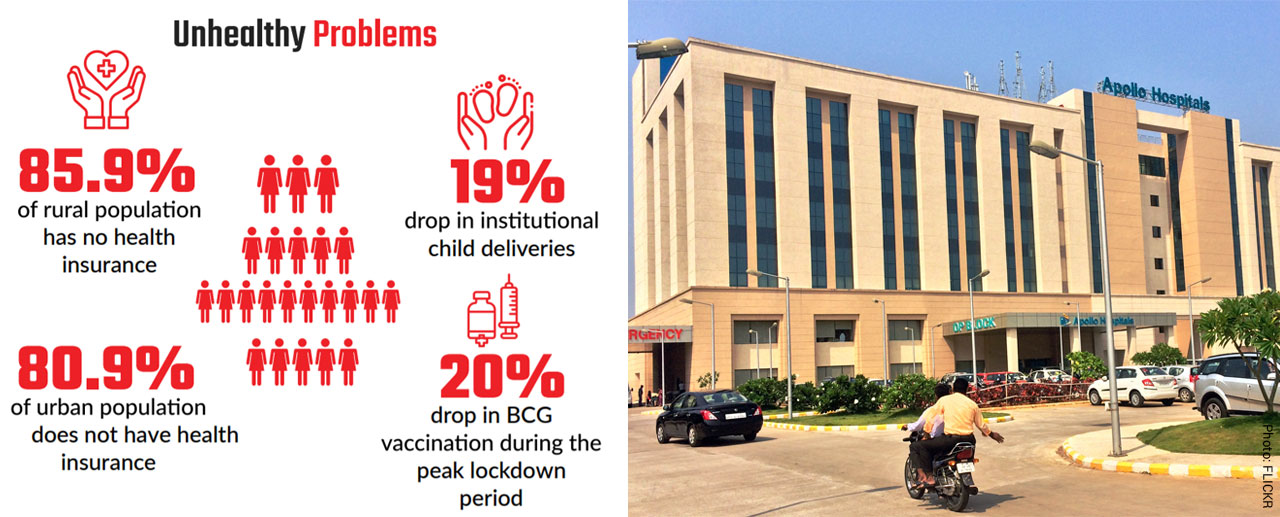

The pandemic disrupted routine health services as people stayed at home during the lockdown, or healthcare resources were diverted to deal with Covid-19 infections. According to the National Health Mission’s Health Information Management System which tracks over 200,000 public healthcare facilities including primary health centres and district hospitals, the number of institutional child deliveries fell by 19 percent from 4.5 million between April and June 2019 to 3.6 million during the same period last year. The number of BCG vaccinations also fell from 5.37 million between April and June 2019 to 4.3 million during the same three months in 2020, a decline of 20 percent.

If rations in kind (as grains) were replaced with cash transfers as some economists had argued, the network of ration shops across the country would have withered away, leaving the poor at the mercy of profiteering private traders

The pandemic showed the mismatch in healthcare facilities between states and between the public and private sectors. The burden of treating Covid-19 fell disproportionately on government hospitals which are fewer in number than private ones and have fewer beds, intensive care units (ICUs) and ventilators. According to a study by research scholor Priya Gauttam and her team, India has 69,265 hospitals of which 63 percent are in the private sector, according to official data. Of the 1.9 million hospital beds, 62 percent are in private hospitals. The same proportion of ICU beds–94,961 in all–and ventilators, which total 47,481, are privately owned.

Most of the government hospitals were overburdened, underequipped, and understaffed during the first wave of Covid-19 infections. India’s reliance on private hospitals proved to be the wrong strategy as they were found to be profiteering. With 85.9 percent of the rural population and 80.9 percent of the urban population having no health insurance cover, private healthcare often means economic ruin.

As medical journal The Lancet’s ‘Citizens Commission’ asserted, India needs universal healthcare and a robust public healthcare system which is affordable and accessible to all, and where the state takes the leadership role as provider, financier and regulator.

For Current Affairs, Follow Tatsat Chronicle on Facebook, Twitter and get connected to us on LinkedIn