Thousands of fish surfaced dead in the Yamuna, at Burari, Delhi, in the early summer of 2025, just weeks before the monsoon. The scale of the die-off, widely reported by the media, left little doubt that it was the result of human negligence rather than natural causes. The National Green Tribunal took Suo-motu cognizance of the incident, recognizing it as a serious regulatory failure.

On Sept. 17, 2025, the tribunal directed the Central Pollution Control Board, in coordination with pollution authorities in Delhi and Haryana, to determine responsibility for the release of toxic effluents into the river. An eight-week deadline was set for a report. That deadline has now passed without any findings made public, any corrective measures announced, or any accountability fixed. What has followed instead, are official meetings to discuss setting up a monitoring system—an implicit admission that basic safeguards for one of India’s most polluted rivers were never firmly in place.

Tribunal Orders Action Against Polluters of the Ganga and Yamuna

A little more than six weeks later, the National Green Tribunal again intervened, directing the Central Pollution Control Board to move swiftly against more than 1,650 grossly polluting industries discharging untreated effluents into the Ganga and the Yamuna. The industries—1,679 in all—were concentrated in Haryana (812), Delhi (149) and Uttar Pradesh (704), according to the board’s own findings.

The petition before the NGT pointed to a deeper failure: CPCB directives requiring continuous emissions monitoring are routinely ignored, while enforcement remains “inadequate or token.” The result is predictable. Toxic discharges continue to flow into rivers that are meant to sustain life, not poison it. The tribunal acknowledged both the scale of the violations and the persistence of untreated effluents.

Yet little suggests a serious effort to diagnose the causes of repeated fish deaths or to prevent their recurrence. In a report submitted, in December 2021, the CPCB conceded that Haryana’s pollution control board had relied on outdated analysis, without conducting fresh sampling—an emblematic lapse in regulatory seriousness. There may be lessons here for Indian authorities from how similar failures have been confronted, and corrected, in Europe.

Europe Chose Action Over Delay

Hundreds of thousands of fish were killed in the Oder River, in the summer of 2022, jolting the European Union collectively, and the riparian countries – Germany and Poland separately. The Oder River that originates in the Czech Republic, flows through Poland and Germany, was till recently one of the last near-natural large rivers in Europe. More than 1000 tonnes of fish were killed, along with molluscs, a host of other aquatic organisms, as well as birds and beavers. These species were killed just in a two-month period between July and September 2022, in what the European Union described as the ‘largest ecological disaster’, in recent European river history. The disaster, that wiped out the Baltic Sturgeons that had been re-introduced in the river over the past three years, spurred governments and even the European Union into action to discover its cause and find a remedy.

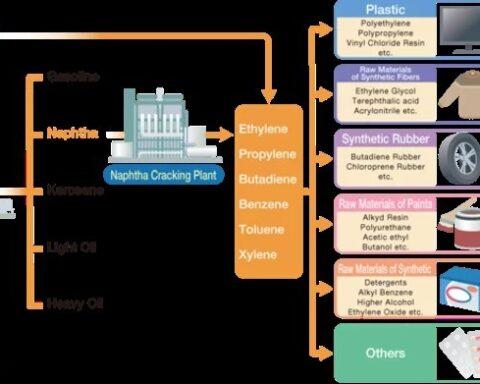

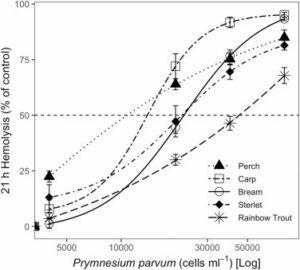

Scientists, researchers and governments turned their attention to discovering the causes of the disaster, and after studying carcasses of the dead fish, concluded that toxins released by an invasive algal bloom was responsible for the death of the fish, over a 500-km stretch of the river in Poland and Germany. The spread of the brackish water alga ‘Prymnasium parvum’ to the upper reaches of the Oder was blamed squarely on human activity. Which included releasing industrial effluents that increased salt concentration in the river, while an overload of nitrogen and phosphorus came mainly from agriculture and wastewater. These factors combined with drought year low flows and high temperatures, created an artificial habitat for the algae that released a toxin which proved fatal for the freshwater fishes.

A multi-disciplinary team of researchers, at the Leibniz Institute and Humbolt University, continue to study the spread of the algae alongwith the production and effects of the toxin, with the latest paper being published as recently as September 2025.

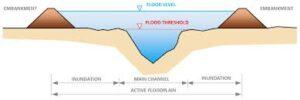

Above all, scientists at the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB), working on the Oder River for decades, put the blame for the disaster on channel engineering. They said channel engineering had interfered with the natural floodplains, that could mitigate flood waves, store water for dry periods and provide refuge for aquatic fauna. “River engineering, embankments and the artificial drainage of floodplains have compromised these functions. The floodplains retain less water, and many backwaters have lost their connection to the main river”, IGB said, in a position paper released in September 2022. The development of the algae would not have been possible, it said under natural conditions in the river.

The IGB report, released a year after the disaster, was clear about one thing – that this was not a natural phenomenon but a man-made problem. It came down heavily on river engineering like channelising, building embankments, dams and barrages and draining out floodplains. It pointed out that engineering was the one reason why stressors like increased salt concentrations and high nutrient loads, (all human created), combined with high water temperatures and prolonged drought, had such an extreme impact on the Oder River. The river’s natural resilience to hydrological and climate change has been greatly reduced.

The Policy Brief further said, “Floodplains act as natural buffers in a river landscape and can mitigate floods, store water for dry periods and provide refuge for aquatic fauna”. It added, “River engineering projects like building dams and deepening the river were not viable solutions for the future”. Findings in freshwater ecology stated,

“Technical measures to regulate rivers increase the risks of such disasters occurring again”. It said, “Dams do not contribute to sustainable water retention. Instead, they facilitate mass development of algae and the evaporation of precious water, prevent ecologically vital sediment transport leading to depth erosion in the river downstream, leading to faster drainage of the adjacent floodplains”.

In 2020 itself, IGB had issued a warning: Poland’s plans of development in the Oder River, with the funding from the World Bank and European Union among others would ‘irreversibly destroy’ valuable habitats on both sides of the river. It pointed out that the near natural conditions in the river existed because it had been of little importance for shipping for the last 100 years and comparatively little investment had been made in the river’s development. Its floodplains provide an important habitat and refuge for many rare and endangered plant and animal species.

Europe’s Response to River Fish Deaths

Immediate suspension of river engineering works including deepening, dams or homogenising riverbeds, restoring the main river and reconnecting it to its backwaters like ox-bow lakes -to ensure more water retention, an advantage during droughts and floods, were among the six recommendations that IGB made to prevent ecological disasters. The huge outcry in Germany and Poland has forced the Polish government to set up three desalination plants. But infrastructure development plans have not yet been set aside though it has set up an inter-ministerial team to check environmental hazards that the Oder River faces.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, Indian authorities seem to be unaware of the experience from the Oder River or even about the serious efforts undertaken by the scientific community in Germany, to analyse the causes of fish kills and suggest measures to prevent the recurrence of such ecological disasters.

The Yamuna incident of fish kills is not an isolated one. Similar ecological disasters have occurred due to untreated industrial waste in several other rivers over the past few years. In December, 2024, the Mula-Mutha River in Pune, in the Gomti (Lucknow) River in June, October and November 2025, in the Yamuna River -Etawah, Mathura and Agra in 2021, in the Angred River, a tributary of the Chambal, in October 2025, in Pithampur, an industrial city near Indore, after a toxic chemical was dumped in the river, in the Chikni River (tributary of Sutlej River) in the Baddi-Barotiwala-Nalagarh (BBN), in Solan district of Himachal Pradesh in October, 2025 when a pharmaceutical company dumped untreated toxic waste in the river. The stock reaction of pollution control bodies appears to be – ‘To limit themselves to collecting water samples for analysis from the affected area’. But the activity is confined for the duration of the public outcry. No report sees the light of the day and neither is any action taken on the ground.

Much the same, indifference is evident in the government’s approach to river-engineering projects, which have already severely depleted the Yamuna’s flow. More than a dozen dams and barrages in the river’s upper reaches now interrupt its natural course, diminishing both water volume and aquatic life.

These interventions are well documented, their consequences widely understood. What remains unclear is whether anyone in authority is listening.