In the early hours of Friday morning, reportedly, Pakistani forces initiated heavy shelling across multiple sectors along the Line of Control, including Poonch, Rajouri, Uri, and Chowkibal in Kupwara district. Over 45 Pakistani drones were intercepted spanning a wide geographic arc from Ladakh to Bhuj—suggesting a broader pattern of aerial incursions attempts.

Amid mounting concerns over regional stability, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio held separate conversations this week with India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, urging both sides to exercise restraint. In his discussions, Secretary Rubio reiterated Washington’s long-standing call for Islamabad to take tangible action to dismantle networks that support terrorism. Mr. Jaishankar emphasized that New Delhi would respond decisively to any escalation initiated by Pakistan.

Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri, speaking at a special press briefing on Thursday, framed the recent Indian military response— Operation Sindoor—as “controlled, precise, measured, considered, and non-escalatory.” Misri asserted that the latest violence stemmed from what he described as a Pakistan-backed terror attack in Pahalgam, which he called the “original escalation.”

Meanwhile, Islamabad’s recent actions at the United Nations raise new questions about its current posture. In the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack in Jammu and Kashmir, reportedly first claimed and then retracted by The Resistance Force (TRF), an offshoot of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT). Pakistani diplomats successfully lobbied to have TRF’s name omitted from an official UN statement. To many observers, the act appeared less like diplomacy and more like shielding. Further, critics say, omission suggested more than just standard diplomatic caution—it appeared to signal a willingness to shield militant affiliates from international scrutiny.

Ishaq Dar, Pakistan’s deputy prime minister made a statement in the Senate a few days ago. He claimed that Islamabad had managed to convince the United Nations to remove mention of ‘Pahalgam’ and ‘The Resistance Front’ (TRF), which was responsible for the killing of 27 tourists in the Baisaran meadow in Pahalgam, in Jammu and Kashmir on April 22. The admission made by the Pakistani minister in the Senate, only confirms what India has been saying since the attack that Islamabad was involved.

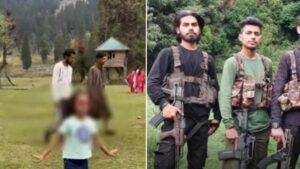

PAKISTAN’S TERRORIST STATE UNVEILED – CAUGHT ON CAMERA

The Hindustan Times subsequently reported that J&K police had identified four persons as perpetrators of the Pahalgam attack. Of these, two Pakistani nationals are Ali Bhai alias Talha and Asif Fauji, while the two locals were identified as Adil Hussain Thoker (from Anantnag) and Ahsan (from Pulwama). Police are also searching for one of the main perpetrators

of the attack in Pahalgam, Hashim Musa aka Asif Fauji/Suleiman, a TRF leader and former Pakistan SSG commando. His involvement caught on camera in the Pahalgam attack, was confirmed through the interrogation of one of fourteen Over Ground Workers (OGWs) arrested in connection with the incident. The NIA states that Musa was likely involved in at least three other attacks earlier on security forces and non-locals in 2024.

In October 2024, terrorists killed seven civilians working at a construction site in Gagangeer of central Kashmir’s Ganderbal district. Followed by an attack on the Indian Army vehicle in the Bota Pathri region of Baramulla district, as it was en route to the Nagin post in the Affarwat range close to tourist hotspot Gulmarg, killing army personnel and porters. Now, the terrorist strike on tourists in Pahalgam has once again brought focus back on the perpetrators of terror operating from Pakistan over the last year.

The National Investigation Agency (NIA), probing the Pahalgam terror attack, is trying to join the dots between Gagangeer, Gulmarg and Pahalgam. The probe so far has revealed that Pakistani terrorist Hashim Musa alias Suleiman is the common link to these attacks as technical evidence has revealed his common involvements in all three modules.

Sleuths however found that the modus operandi and the weapons used by the terrorists this time in Pahalgam attack were more sophisticated, supported with night vision devices, MP3 machine guns, AK 47s and other weaponry in their kitty. The module was better trained, with good fire discipline, recce and better planning. The three attacks may have been geographically apart but were sensational enough to keep the forces confused.

Between 2019 and 2022, 108 of the 122 armed fighters killed in gunfights in J&K were affiliated with TRF, according to government records says Al Jazeera. In June 2024, TRF also claimed responsibility for an attack on a bus carrying Hindu pilgrims, killing at least nine people and injuring 33, in Jammu’s Reasi area. The supreme commander of TRF is Sheikh Sajjad Gul and Basit Ahmed Dar is the operational head. It has been involved in major killings, including the October 2024 Ganderbal attack targeting non-local labourers and a doctor. Initial cadres for TRF came from the HM and LeT. Thus, it is seen that TRF was initially aimed to be an online platform for radicalisation, but later it converted into a physical organization with cadres recruited from various groups including the LeT at the behest of the ISI.

A NIA press note of 2021 states that searches carried out in Srinagar and the arrest of a TRF operative Arsalan Feroz were related to a conspiracy hatched to ‘radicalise, motivate and recruit’ the youth of Jammu & Kashmir and give effect to violent activities. Names mentioned in the NIA note include Sajjad Gul, Salim Rehmani @ Abu Saad and Saifullah Sajid Jutt, Commanders of LeT/TRF. The TRF was alleged to be recruiting individuals (OGWs) to carry out reconnaissance of pre-determined targets, coordinating and transporting weapons to support LeT and its ‘frontal affiliate’ TRF. Sajjad Gul’s name also appeared in a NIA First Information Report filed in November 2021. Both Sajid Jutt and Salim Rehmani (Pakistani nationals) were displayed on posters put up by the NIA in Srinagar in 2022.

Afsara Shaheen writing on the South Asia Terrorism Portal in 2024 quoted a senior police J&K police officer who describes the TRF in the following words. “The name TRF was an attempt to secularise the idea of jihad to present the Kashmir insurgency as a political cause rather than a religious war as was manifested by the names such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and the Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM).” In other words, the deep state in Pakistan wanted to de-Islamise and localise the terrorist movement in Kashmir to ensure that terrorist activities could not be traced back to Islamabad and the ISI.

The LeT and its cadres are all based in Pakistan and it has many affiliates like the TRF. The perpetrators of the Pahalgam attack is Pakistan and therefore, India’s response accordingly. For too long, the psychological scar from attacks like 26/11 in Mumbai, URI, Pulwama and Pahalgam have festered. India needs to respond to Pakistan with a message to its own people that they remain on guard to protect every citizen.

Despite the undeniable evidence that points to ISI/LeT/TRF being behind the Pahalgam attack, Pakistan continues to deny any involvement in terror activities ever. Common sense dictates an understanding of the nebulous nature of terrorist organizations and the ISI’s capacity to transform terrorist entities to escape international scrutiny and continue operations.

A Familiar Reckoning in Pakistan AKA Terror-istan

Recent statements by senior Pakistani officials have once again brought the country’s complex and controversial history with extremist groups into sharp focus. Former Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, in an interview with Sky News, acknowledged in early May 2025, what many in the international community have long alleged—that Pakistan’s involvement with

terrorists, in his words, “I don’t think that it’s a secret that Pakistan has a past as past as far as extremist groups are concerned.”

His admission follows an even more direct statement from Pakistan’s current Defense Minister, Khawaja Asif, who conceded in a televised interview that the state had supported and financed militant groups dating back to the Afghan conflict of the 1980s.

“We have been doing this dirty work for the United States for about 3 decades… That was a mistake, and we suffered for that,” he said. These revelations, unusually direct for sitting and former government officials, suggest a limited but notable departure from the denials that have characterized Pakistan’s official line for decades.

A Public Farewell That Reveals Pakistan’s Enduring Ties to Extremism

According to reports, Masood Azhar, the leader of Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), claimed that ten of his relatives were killed in India’s missile strikes during Operation Sindoor on May 7, 2025. The targets included a LeT building near Bahawalpur. The strikes were part of India’s retaliation for the Pahalgam attack. Further, Indian Armed Forces’ precision strikes on Terror hubs in Pakistan, reportedly killed Abdul Rauf Azhar, the operational head of JeM and mastermind of the IC-814 hijacking. Azhar was involved in the kidnapping and murder of Wall Street Journal journalist Daniel Pearl in 2002.

In a stark reminder of Pakistan’s enduring ties to proscribed terrorist organizations, a recent funeral in Muridke, near Lahore, underscored the state’s complicity. Hafiz Abdul Rauf, a senior figure in Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), led prayers for three men—Qari Abdul Malik, Khalid, and Mudassir—reportedly affiliated with Jamaat-ud-Dawah (JuD), the banned group founded by Hafiz Saeed, the alleged mastermind of the 2008 Mumbai attacks. The ceremony was attended by members of the JuD, personnel from the Pakistan Army, police officers, and civil bureaucrats. In a striking display of state endorsement, the coffins were draped in the Pakistani national flag—a gesture typically reserved for national martyrs, not members of internationally designated terrorist organizations.

This public display underscores the deep entanglement between Pakistan’s state apparatus and extremist groups. The recent funeral ceremony serves as a stark reminder of the state’s ongoing complicity and the challenges in addressing the nexus between state institutions and terrorist networks. Such overt displays of solidarity not only weakens Pakistan’s claims of combating terrorism but also reinforce international concerns that elements within the state continue to legitimize, protect, and even honor individuals tied to banned terrorist outfits.

Pakistan’s Militant Nexus: A Network of Global Terror Ties

For over three decades, the trail of global Islamist terrorism has passed, in some form, through Pakistan. From the 9/11 plotters to the 2008 Mumbai attacks, and from deadly bombings in London to insurgencies across South Asia, the evidence is both voluminous and damning: Pakistan continues to serve as a staging ground, sanctuary, and support system for militant actors operating far beyond its borders.

The problem is not peripheral. It is foundational. Pakistan’s security establishment—particularly its powerful Inter-Services Intelligence agency—has long enabled groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba, Jaish-e-Mohammed, and The Resistance Front, many of which are linked to Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Despite international designations and sporadic crackdowns, these groups persist, often under new names and with continued ideological cover. Despite international sanctions, Pakistan remains home to organizations like the Karachi-based Al-Rashid Trust, which was designated by the U.S. in 2001 for financing global Islamist terrorism. Similarly, Lashkar-e-Taiba, one of the most lethal and well-organized militant groups operating in South Asia, continues to function within Pakistan—often under the guise of charitable work—despite its direct links to major attacks, including the 2008 Mumbai massacre.

Even more troubling is the history of Pakistan’s nuclear scientists reportedly interacting with terror networks. In 2002, U.S. intelligence uncovered evidence of direct contact between Osama bin Laden and two senior Pakistani nuclear scientists, Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood and Abdul Majid. Islamabad’s decision not to prosecute those involved only deepened global concerns about the state’s willingness—or ability—to control its most dangerous assets.

Despite periodic cooperation with the United States and other allies, often under diplomatic or financial pressure, Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts have appeared more performative than structural. Arrests have frequently come only after foreign intelligence has forced Islamabad’s hand. Public denials from Pakistani leadership regarding the presence of terror figures on their soil have repeatedly been disproven, most famously when Osama bin Laden was discovered living in Abbottabad. Figures such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammad and Yasir al-Jaziri were not captured in remote tribal areas or impoverished madrassa enclaves, but in affluent neighborhoods of Karachi and Islamabad—districts largely populated by military officials and civil servants. In at least one instance, a serving Pakistani army major was implicated in harboring a top terrorist figure. These details point to a deeper, more systemic problem: elements within Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have long sustained covert ties to extremist groups.

The situation is further complicated by the blurred lines between Pakistan’s political elite and extremist factions. Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), another group with deep roots in Pakistan, was reportedly founded by Masood Azhar with the backing of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the Afghan Taliban, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), and several Sunni extremist factions within the country, according to Australian national security sources.

Figures like Masood Azhar—implicated in numerous high-profile attacks, including the 2001 Indian Parliament assault and the 2019 Pulwama bombing—have operated for years with relative impunity. While international pressure has at times resulted in brief detentions or asset freezes, there has been little meaningful accountability.

Masood Azhar’s militant pedigree stretches back to the mid-1990s, when a group linked to Harkat-ul-Mujahideen—an early incarnation of his later outfit, Jaish-e-Mohammed—kidnapped six Western tourists in Jammu and Kashmir, demanding his release. One hostage was killed, and the rest were never found. U.S. intelligence later confirmed Harkat’s role in targeting Westerners to further its extremist agenda. Azhar’s influence extended far beyond South Asia; the BBC once called him “the man who brought jihad to Britain,” citing his ties to individuals connected with multiple major terror plots – 7/7 London bombings, the 21/7 attempted attacks, and the 2006 transatlantic airliner bomb plot. IC814 hijacking was led by Masood Azhar’s brother, Ibrahim Athar and his younger brother Abdul Rauf Asghar had planned this attack.

Additional reporting from GlobalSecurity.org notes, reports of direct financial backing from al-Qaeda and its alleged political ties to Pakistan’s Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (Fazlur Rehman faction), blurring the boundary between extremist violence and mainstream politics. The U.S. Treasury has sanctioned key operatives and front organizations linked to JeM, including the Al Rehmat Trust, which it identified as a logistical and financial conduit for the group. JeM founder Masood Azhar has been designated a Specially Designated Global Terrorist, placing him and his network squarely under international sanctions.

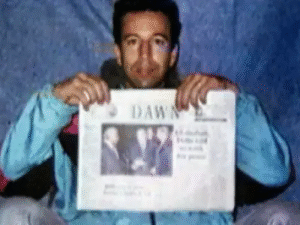

Air India flight IC-814 were taken hostage by the militants of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, Source IC814.com

Stanford University’s Mapping Militant Organizations project outlines how JeM has cultivated operational ties with a constellation of jihadist actors, including the Taliban, al-Qaeda, LeT, Al-Rashid Trust, and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi. This dense web of relationships has made the group one of the most interconnected and resilient players in South Asia’s militant landscape.

Stanford University’s Mapping Militant Organizations project outlines how JeM has cultivated operational ties with a constellation of jihadist actors, including the Taliban, al-Qaeda, LeT, Al-Rashid Trust, and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi. This dense web of relationships has made the group one of the most interconnected and resilient players in South Asia’s militant landscape.

The notion that Pakistan’s challenges with extremism can be addressed through development aid is a persistent illusion. International financial assistance has often freed up domestic resources for militarization and religious radicalization rather than fostering reform. The deeper issue lies in the ideological foundations of the Pakistani state and the entrenched alliance between the military, religious hardliners, and militant proxies. Real change will require more than new leadership—it demands a structural transformation in governance and ideology. Until then, Pakistan remains not merely a sanctuary for militant groups, but a central node in the global terror network.

Together, these connections reveal a sobering reality: Pakistan remains not just a host to militant groups, but a hub of ideological, financial, and operational collaboration among globally sanctioned terrorist entities.

********

Author: Dr. Bhashyam Kasturi and Dr. Sumi Gupta