It was a lifelong dream for Dimhau to own a beauty parlour. After training as a beautician, she realised her life’s ambition by opening a beauty parlour in Lamka district, Manipur, (also known as Churachandpur) on May 1. But little did she know her dreams would go up in flames in just 48 hours.

On May 3, when ethnic violence engulfed the state with Kuki and Zomi tribes on side and the majority Meiteis on the other, Dimhau was forced to shut down her beauty parlour. As armed mobs took over the streets, with little signs of police trying to enforce even a semblance of order, ordinary people like Dimhau were the first to be singed by the fury of the mobs. “I opened my parlour on May 1, and the violence began on May 3,” says Dimhau, for whom the parlour was a gateway to a better life.

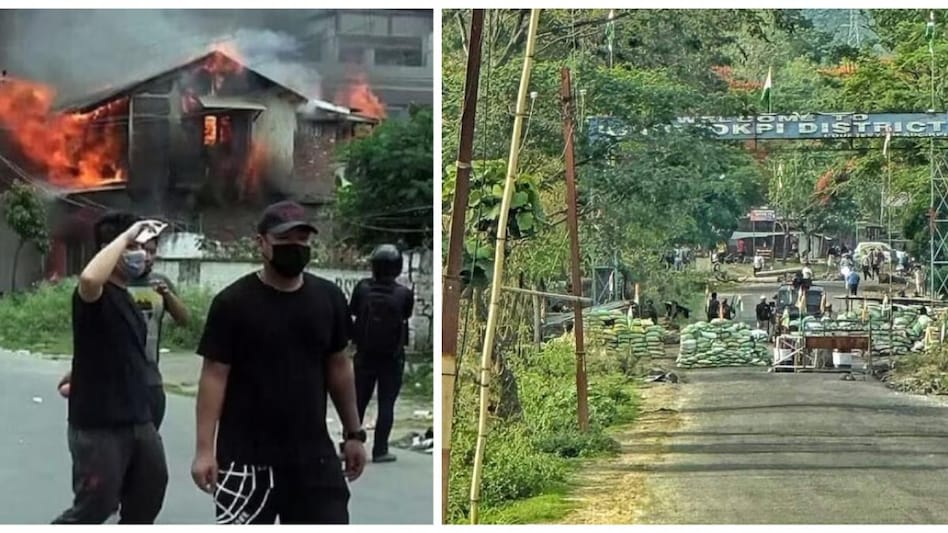

In the ongoing ethnic violence that has lasted more than two months, Lamka and Imphal have been the biggest hotspots and have seen largescale loss of property and life. Today, the entire state stands divided along ethnic lines. The breakdown of the state’s administrative machinery is complete as the killings, arson, and mob rampages show no signs of abating.

Even when curfew is relaxed for a few hours every day, it’s not of much help to small business owners. In a crisis situation people tend to prioritise essential needs over non-essential needs like visiting a beautician. “Even if I open my parlour, no one comes because of this crisis. They have other priorities,” says Dimhau. The local economy has crashed to such an extent that civil society has appealed to landlords not to charge full rent. “This is a small relief,” says the grocery shop owner in Lamka. “Even when the shop is open, people buy only essential items…mainly food items. We don’t know for how long the landlord will give discount on the rent.” The earnings of local business owners have crashed since May 3.

In the ongoing ethnic violence that has lasted more than two months, Lamka and Imphal have been the biggest hotspots and have seen largescale loss of property and life. Today, the entire state stands divided along ethnic lines.

Even the availability of essential items is becoming more difficult with each passing day, and prices have shot up due to erratic supply because of the blockade of National Highway 2 (NH-2) — the lifeline of Manipur. The 436-km highway originates at Numaligarh in Assam, connects Manipur and Nagaland to the rest of India, and goes all the way to Moreh on the India-Myanmar border. All goods coming into Manipur, including life-saving drugs, have to pass along this highway.

Given the significance of NH-2 for the movement of goods and people, it’s often blocked as a tool of political blackmail. This crucial highway has been blocked hundreds of times over the years by various political groups who lord over it. This time, NH-2 was blocked by Kuki groups in retaliation against the Meiteis, who predominantly inhabit the Imphal valley. Imphal being the commercial hub, any blockade of NH-2 results in disruption of supply of goods to the hill districts which are located deeper in the state.

According to a 2017 study by P.R. Chiru, assistant professor, Department of Management, Sanai International University, Manipur, the economic loss due to the blockade of NH-2 in 2010-11 was estimated to be ₹239.2 crore, in 2011-12 it was ₹553.23 crore and in 2012-13 it amounted to ₹520.73 crore. The Department of Economics and Statistics of the Government of Manipur estimated that the 120-day blockade of NH-2 in 2017 caused a loss of ₹2.67 crore per day to the state’s exchequer. These losses did not include destruction of property and vehicles that were torched by the mobs.

The other economic lifeline is NH-37, connecting Imphal with the Jiri-Silchar road. When NH-2 is blocked, this road manages to keep the state supplied with essential commodities. But, being a more circuitous route, the freight costs increase, which impacts prices. To keep southern districts like Churachandpur supplied, traders have to rely on the Silchar-Aizawl-Churachandpur road in such times. “It takes more than 36 hours to complete the journey in one direction,” says Mangkhum, a trader of essential food items who plies between Silchar and Churachandpur. “It’s such a long journey that the freight is very high…we have no choice except to increase the prices.”

When the situation is normal, the hill districts remain poorly supplied because most of the distribution hubs located in the Imphal valley prioritise supplying the more densely populated neighbouring areas first before venturing deeper into the state. When there are blockades, the people in the hill regions have no option but to depend on supplies from neighbouring states.

The majority of the rural population, dependent on agriculture, suffers due to the difficulty in movement at times of social strife. Handloom, which is another major economic activity, too takes a hit, impacting the livelihoods of women. Other small businesses bear the brunt whenever there is turmoil in the state.

Rebati, a woman farmer from Bishnupur district, told me that she is unable to tend to her fields in the foothills due to fear of violence. In rural Manipur, there are many farmers like her who are unable to plant rice during this planting window due to apprehensions of mob violence. “As of now, we are dependent on the kitchen garden, fish from the pond near our homes and our grain stock,” says Rebati. “We are currently unable to cultivate our land in the foothills.”

Even in peaceful times, Manipur has been importing rice from other states such as Punjab. Now, with the NH-2 blockade, the rice stock in the state is likely to deplete in the near future. According to media reports, in early July the president of the Irabot Foundation, Gopen Luwang, warned that a prolonged crisis could lead to widespread starvation in the near future. Civil society organisation have assessed that this year’s rice production in the state could witness a significant deficit of about 40,000 metric tonnes due to the ongoing crisis.

Rebati, a woman farmer from Bishnupur district, told me that she is unable to tend to her fields in the foothills due to fear of violence. In rural Manipur, there are many farmers like her who are unable to plant rice during this planting window

Like any other state, Manipur too is recovering from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the present crisis perpetuated by ethnic violence comes as a severe setback and is likely to leave a lasting impact on the state’s economy. Even during the pandemic lockdown, the intra-state connectivity was not affected. Now, however, with the internet shutdown and road blockades all over the state, traders and small businesses in Manipur are facing grim prospects.

Before the current cycle of violence broke out on May 3, Manipur was taking strides in the tourism sector. A clutch of high-profile events such as hosting of one of the G20 working group meetings, the Femina Miss India final, and the Sangai Festival were aimed at projecting the state as a viable tourism destination. In 2019-20, Manipur had a tourist footfall of 179,436 visitors, out of whom 12,102 were foreigners.

Even if the violence stops in the near future, it will take years for Manipur to recover from the severe economic setback. This round of ethnic violence, unlike any in the past, has already left deep scars on society and has created a massive trust deficit. The longer the intra-community tensions are allowed to simmer, the longer it will take Manipur to bounce back and alongside the government’s ‘look east’ policy will be consigned to oblivion.