The story of largescale land subsidence in the hill town of Joshimath in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand is what an existential crisis looks like in real life. It’s also a story that foretells what the future holds for many of the Himalayan towns that have evolved into concrete Lego blocks, stacked atop one another, waiting for one major natural disaster to bring them crashing down like a house of cards.

The Joshimath story has as many acts and subplots, if not more, as any Greek tragedy—quirk of nature, human avarice, bureaucratic sloth, administrative and corporate chicanery, state-sanctioned remorseless exploitation of natural resources, contempt for ecological sensitivity, and the chasing of the development mirage. Ultimately, it’s the people, who also played their part in the story—sometimes knowingly, sometimes unwittingly—who are paying the highest price.

At the time of writing, approximately 900 houses and commercial establishments in some worst-affected localities of Marwari, Manohar Bagh, Gandhi Nagar, and Singdhar have been either marked as unsafe or identified for demolition after developing cracks in the walls and floors due to massive subsidence. Gangs of construction workers in yellow hard hats and fluorescent bibs, contracted by the State Disaster Management Authority, are working heavy earth moving equipment and sledgehammers to pull down buildings and houses marked for demolition. The sound of industrial equipment crashing into concrete rents the air like doomsday reverberations.

At the time of writing, approximately 900 houses and commercial establishments in some of the worst-affected localities have been either marked as unsafe or identified for demolition

“We completed building the extension to our house just a year ago for the purpose of renting. But now it has been marked for demolition,” says Usha Bhandari, resident of Manohar Bagh, pointing to the red (unsafe) and black (demolition) stickers that the officials from the Central Building Research Institute (CBRI) have stuck on the outer walls of the pleasant living room that overlooks a clump of Malta orange trees. “We don’t even know how much compensation the government will pay, if it pays at all.” The crack-meters installed by CBRI officials on the walls of her house record the ever-widening crevices through which the settled life of her family is slipping into the darkness of the earth.

As one walks down the winding footpath that connects Manohar Bagh to the tehsil office through the main bazaar on either side of the Joshimath-Badrinath highway, one sees and hears iterations of the same story with slight variations in the impact the disaster has had on families’ lives. The thread of being uprooted from the only place most of them have ever known and the looming loss of livelihood strings the Joshimath tragedy that’s unfolding a centimetre at a time.

In the tehsil (local administration) office, hundreds of men and women have been protesting under the banner of the Joshimath Bachao Sangharsh Samiti (JBSS) since early January, when the news of Joshimath’s subsidence made national headlines. They paint a grim picture of despondence and official apathy, even as Uttarakhand Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami continues to issue banal statements that gloss over the gravity of the unfolding catastrophe.

On the ground, the narratives shared by people grappling with the worst crisis in their lives are far removed from the parallel universe in which the BJP-led state government has sought refuge. On January 25, Dhami proclaimed that 70% normalcy had already returned to Joshimath even as more houses developed cracks. The president of the party’s state unit, Mahendra Bhatt, went a step further to slander the agitators, whose lives have been uprooted overnight, as “Maoists” and “China agents”.

As one walks down the winding footpath that connects Manohar Bagh to the tehsil office through the main bazaar on either side of the Joshimath-Badrinath highway, one sees and hears iterations of the same story

These utterances by the ruling party’s politicians sound like glass shards in the ears of women like Gita Parmar, whose family had to vacate their ancestral home. “The past 25 days have been horrifying. The government has given us one room for my family of eight in which we are forced to live like cattle,” she says. “Some days we get food, on other days we are left to fend for ourselves. Our children are in a state of depression. My daughter was scheduled to appear in the pre-board examination, but she is in no state to take it. They want to go back to their home but can’t because the cracks are widening by the day.”

“On the morning of January 5, when we woke up, we noticed huge cracks in the floor of our house and of our neighbours,” narrates Tulika Devi of Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 1. “We immediately informed the administration and that’s when we came to know that houses in other areas too have either tilted or developed cracks. It’s like we have been hit by a tragedy.”

On the bitterly cold morning of January 2, hell broke loose in the town of roughly 25,000 people when news spread of a massive breach in the boundary wall of JP Colony in Marwari through which a torrent of muddy, silt-laden water gushed. Over the next few days, cracks started appearing in the walls of houses, shops, and on the Joshimath-Badrinath highway that bisects the main bazaar under the looming backdrop of Haathi Parvat (Elephant Mountain). As more houses developed cracks or started sinking, panic and chaos reigned in the area, with a clueless administration failing to provide answers to citizens.

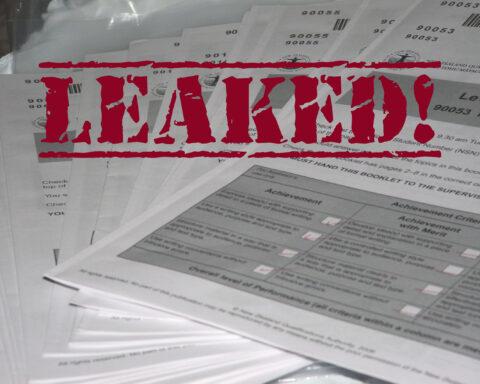

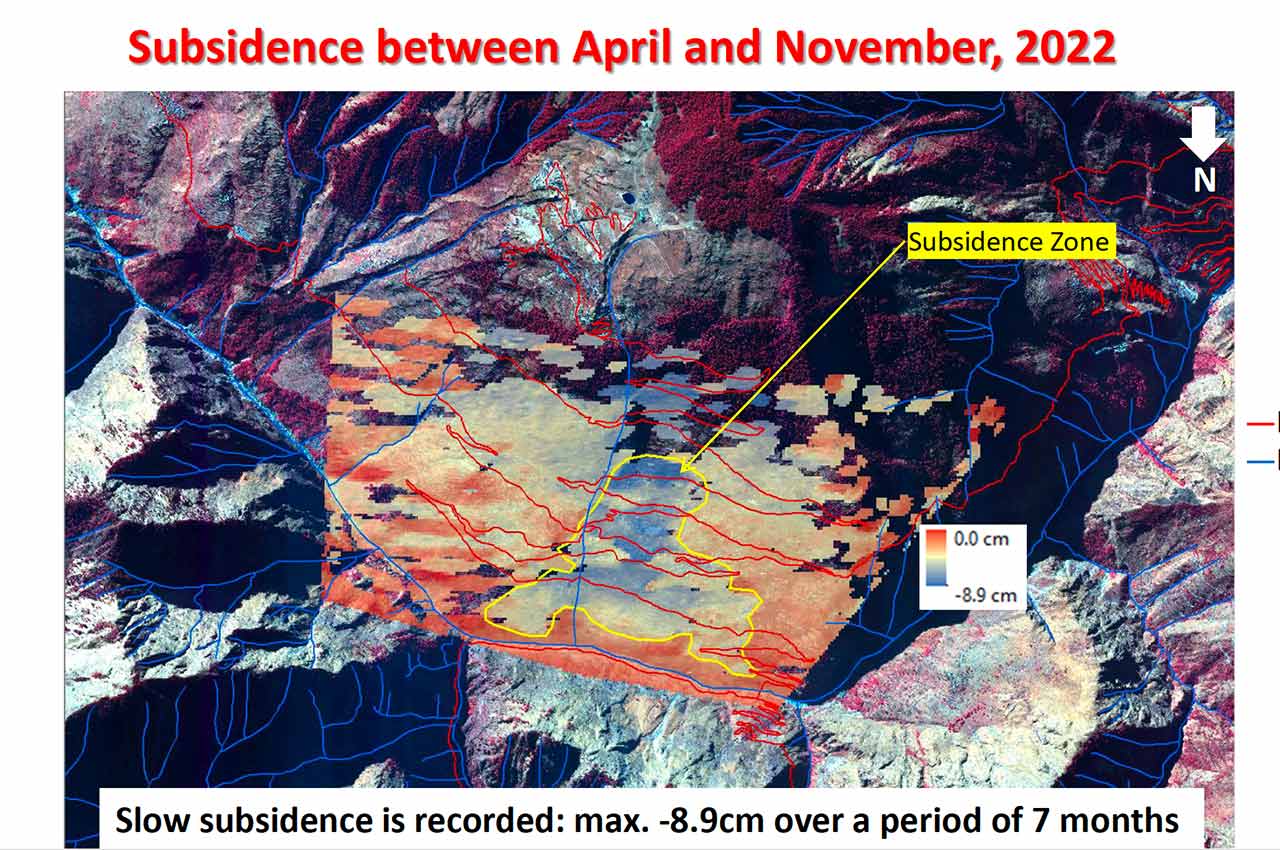

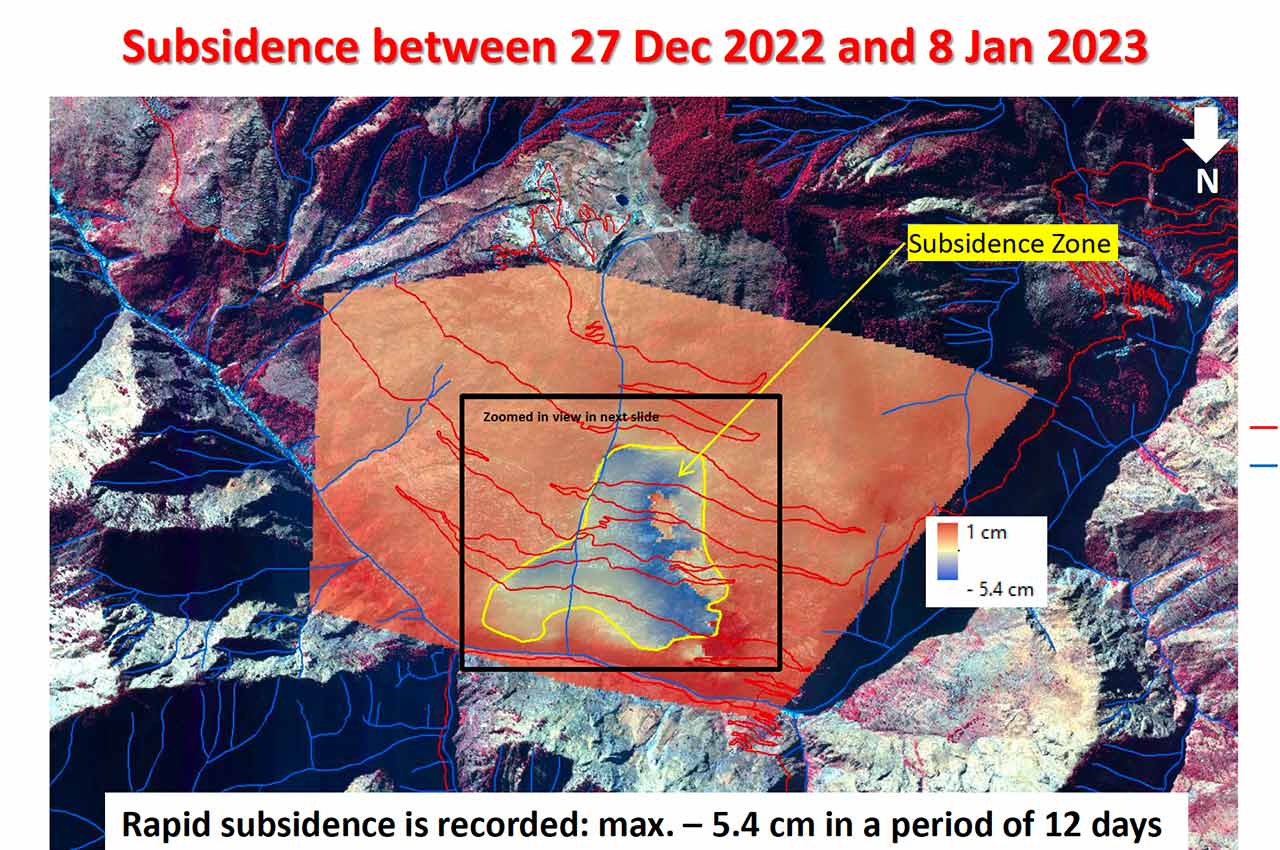

On January 13, the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) released a short report based on the analysis of satellite data. It noted that between December 27, 2022, and January 8, 2023, rapid subsidence of 5.4 cm was observed compared to the slow subsidence of 8.9 cm that was recorded over the seven-month period of April to November 2022. In other words, the slow creep of the slope on which the town rests was already taking place before the events of January this year took over. However, ISRO was forced to remove this report from its website after the Ministry of Home Affairs issued an office order through the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) on January 14, putting a gag on all government officials and organisations sharing any data or information about Joshimath’s subsidence.

On January 13, the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) released a short report based on the analysis of satellite data

Unique geography, fragile ecology

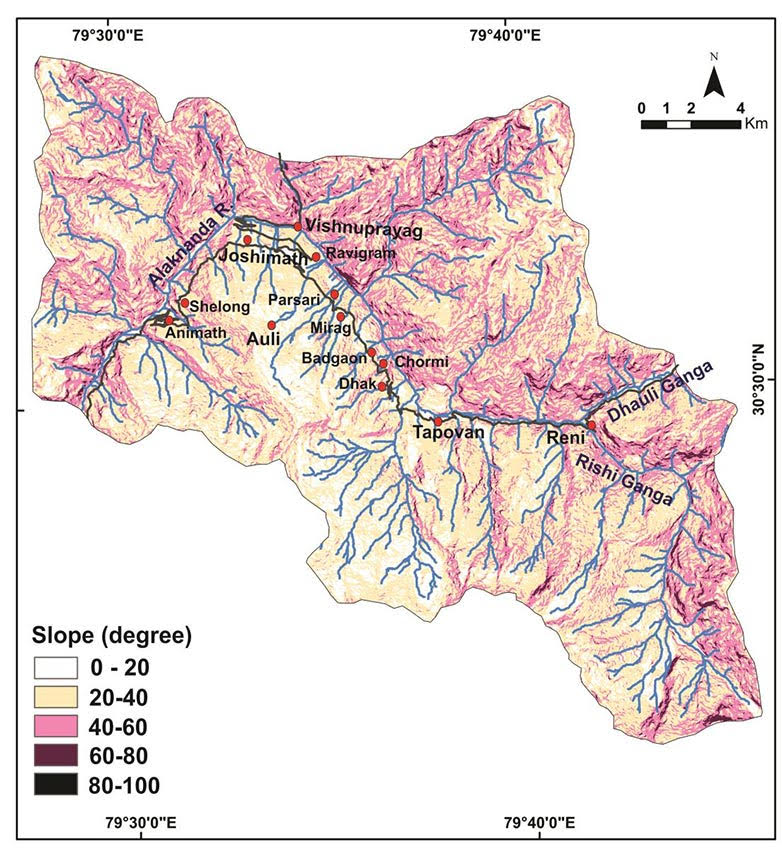

The tragedy that’s now unfolding in Joshimath in slow motion has been in the making for more than five decades. The construction of largescale hydro power projects that involves blasting rocks using dynamite and drilling tunnels through the mountains despite dire warnings sounded in multiple government and non-government reports about the fragile ecology of the surrounding areas, excessive construction to cater to religious tourists on the Char Dham Yatra, Jyotir Math and Hemkund Sahib pilgrimages with no regard for building byelaws, lack of civic infrastructure like sewage systems and impermeable drains carrying household wastewater, widening of NH 7 that entailed hacking neck-craning cliffs with gradients ranging from 50O to 70O and, finally, a quirk of nature have coalesced to script this environmental disaster. But the human imprint on the disaster is undeniable.

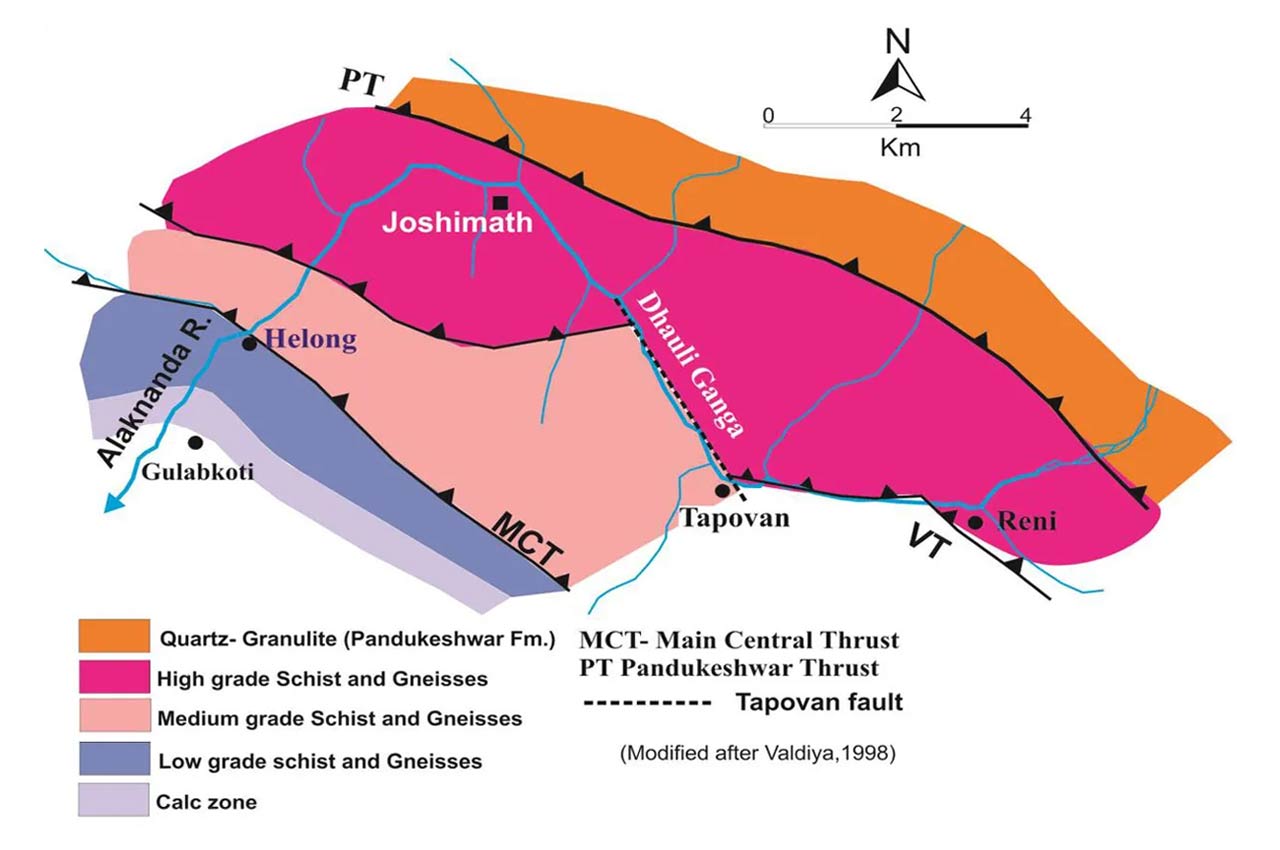

Joshimath lies on the brow, approximately 10 km northeast of the MCT, which runs from Helong in the west to Tapovan in the east. It has been identified as the most seismically active zone

To begin with, one needs to travel back to the time of the continental drift that gave birth to the Himalaya when the Indian plate got pushed under the Eurasian plate, creating a tectonic arc called the Main Central Thrust (MCT). The MCT runs through the length of the mountain system, stretching for more than 2,900 km from the Eastern Karakoram in the northwest to the Eastern Himalaya in Arunachal Pradesh. The MCT is not a sharp cut in the plates, it is rather a shear zone with width ranging from 5 km to 20 km. The area north of the MCT is para-glacial, referring to ancient moraine deposits after the glaciers receded.

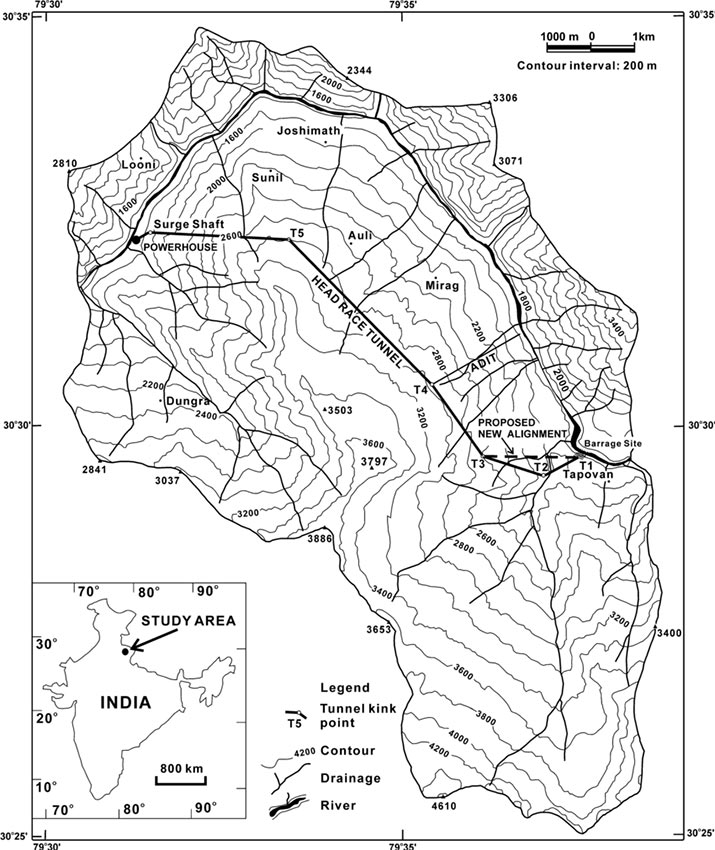

Joshimath lies on the brow, approximately 10 km northeast of the MCT, which runs from Helong in the west to Tapovan in the east (see Figure 2). It has been identified as a Grade 5 seismically active zone. But that’s not all.

Sometime in the ancient past, a massive landslide cascaded from the high mountains up north, bringing down with it a mass of glacial and glaciofluvial debris (boulders, rocks, silt, clay and so on) that settled on a concave bowl of schist. “Joshimath is located on old landslide deposit which was first reported by Heim and Gansser way back in 1939. According to them, the slopes dominated by massive boulders between Joshimath and Tapovan were triggered by a landslide in the geological past from a mountain crest located at ~4000 m in the east of Kauri pass,” notes a publicly released research report that was commissioned by JBSS last year. The report is authored by S.P. Sati, head, Department of Basic and Social Science, College of Forestry, Ranichauri; Navin Juyal, former geologist with Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad; and Shubhra Sharma, assistant professor, Physical Research Laboratory.

“The seismically active nature of the terrain is manifested by highest uplift rate of around 2 mm/yr around Joshimath. Geomorphologically the terrain around Joshimath encompasses both glacial and glacio-fluvial landforms. The slopes are dominated by precipitous slopes covered with gigantic fans and cones of active and stabilised landslide debris,” write the authors of the report.

The slopes and mountains in the area surrounding Joshimath are dominated by a large number of streams that disgorge glacial melt, originating above 4,000 metres, into the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers

The sharp elevation gain between Helang (Helong) at 1,551 metres (5,089 feet) and Joshimath at 1,875 metres (6,150 feet) makes it a natural barrier to the annual South-West Monsoon or the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM). “The average annual precipitation is around 1,500 mm of which around 80% is contributed by the ISM and many a times cloud bursts on the precipitous slopes of the MCT zone is common. Since the rocks are sheared and fissile, which makes the slopes around Joshimath extremely vulnerable to slope destabilisation,” write Sati et al.

Further, the slopes and mountains in the area surrounding Joshimath are dominated by a large number of nullahs (streams) that disgorge glacial melt, originating above 4,000 metres, into the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers (Figure 2). Most of these streams are fast-flowing and bring down a considerable quantity of silt, moraine and boulders left behind in the receding glacier era along with summer snowmelt and monsoon rain. Cloudbursts in the steep gorges of these water channels during the monsoon are common, releasing an enormous cascade of water. The mix of debris and water causes severe erosion of the mountain spurs, or toe cutting, and triggers large landslides.

These streams are not only the source of life-sustaining water for the villages, they also charge the subterranean springs, which are the cleanest source of potable water and support aquatic life like snow trout. The aquifers, fed by these streams, act as load-bearing layers. Below the snowline, an ecosystem of alpine grassland and forests provides stability to the steep slopes and hosts a wide variety of mountain fauna. On the flip side, the hydropower companies see these streams as their wet dreams in a literal sense. For them, they represent vast untapped potential for hydro-electric power to meet India’s rising demand for electricity. Therein lies the rub.

According to the Supreme Court-appointed, 11-member Expert Body (EB) report—set up under reputed environmental scientist Ravi Chopra of the People’s Science Institute in the aftermath of the Kedarnath disaster in June 2013—the state can potentially harvest 27,039 MW of hydropower by setting up 450 small, medium and large projects. “So far 92 projects with a total installed capacity of 3,624 MW have been commissioned. Of these, 15 large and medium projects account for 95% of the installed capacity. Another 38 projects with an installed capacity of 3,292 MW are under construction. Here too 8 large and medium projects account for 97% of the capacity,” says the EB report that was submitted to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change in 2014.

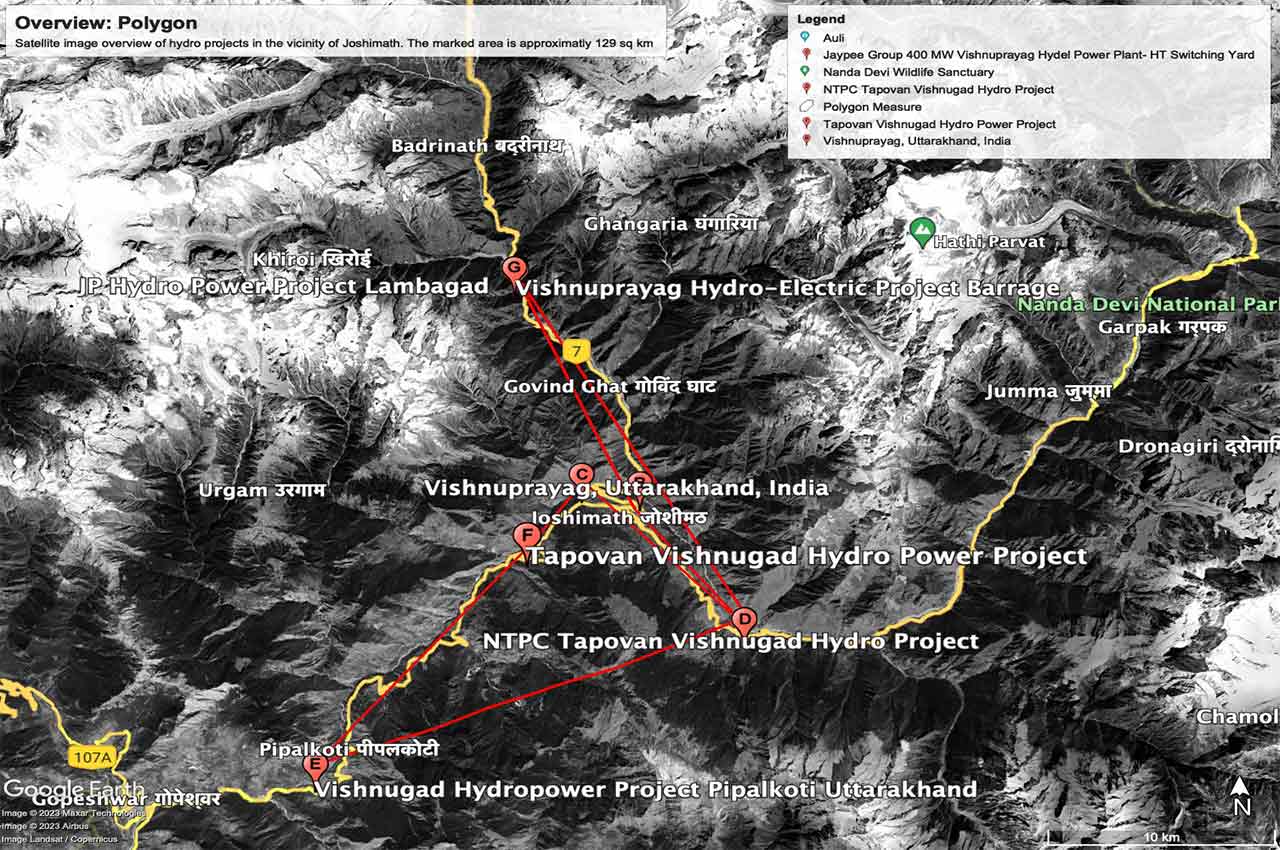

In Joshimath’s case, the town is hemmed in by three large hydropower projects (see Figure 4) —Vishnugad-Pipalkoti (444 MW), Tapovan-Vishnugad (520 MW) and Jaypee Vishnuprayag (400 MW)—with a total power generation capacity of 1,364 MW. All three projects are in various stages of completion, though classified as run-of-river type, involve largescale construction of barrages and boring long tunnels through seismically active and landslide-prone zones.

In the present instance, the NTPC Tapovan-Vishnugad project is the focus of people’s ire. They hold the ongoing work and a series of past mishaps while drilling the head race tunnel (HRT) responsible for their current predicament. It has an 11.77-km HRT meant to carry water from the barrage at Tapovan (1,789 m) on the Dhauliganga, approximately 8 km upstream of its confluence with the Alaknanda, to the power plant just below Selang (1,356 m) and runs under Joshimath. The townsfolk point out that since the construction of the project started in 2003, there have been signs of trouble. The latest mishap took place in February 2021, when the barrage site suffered substantial damage after an avalanche triggered a flash flood in the Rishi Ganga, which drains into the Dhauliganga, a few kilometres upstream of the project site.

The apprehension is not misplaced. Since its inception in 2003, this project has been dogged by controversy and accidents. Joshimath’s residents point out that the project was set up in gross violation of the recommendations of the Mishra Commission Report of 1976, when Uttarakhand was still part of Uttar Pradesh (UP).

“We have been warning the administration and the concerned authorities for more than two decades about the dangers of constructing large hydropower projects in this extremely ecologically fragile zone,” says Atul Sati, convener of JBSS. “Way back in 1998-99 when the work on Jaypee Vishnuprayag started that involved largescale blasting and drilling, we observed that the toxic dust settled on the grazing land of Chaien village, and cattle and goats started dying. This is the village that was known for supplying milk and milk products right up to Badrinath. The Malta trees died…and by 2007 the houses developed cracks.”

The inhabitants of the hamlet rose in protest at the destruction of their livelihood, but it fizzled out after the company held out a promise of jobs and civic facilities. “In 2001 protests resumed after people realised that they were short-changed and demanded compensation of ₹5 lakh. But police broke up the protest quite brutally, and eventually a compensation of ₹2.5 lakh was awarded to the villagers,” Atul told Tastat Chronicle. Today, Chaien is virtually a devastated village.

In 2003, when surveying for the Tapovan-Vishnugad project started, activists and Joshimath residents wrote to the then President of India, seeking his intervention to cancel the project. The approximately 100-km-long Dhauliganga is a minor river but the last 50 km has six hydropower projects, both large and small.

The townsfolk point out that since the construction of the project started, there have been signs of trouble. The latest mishap took place in February 2021, when the barrage site suffered substantial damage

Tone deaf to early warnings

Joshimath, sandwiched between the MCT and the Trans Himalaya Thrust, has long been identified as a geologically fragile zone. In the late 1960s, the earliest signs of land slippage and slope creep were observed there. When the residents raised an alarm, the UP government constituted an inter-disciplinary expert committee under the chairmanship of M.C. Mishra, Garhwal commissioner, to identify the cause of slope creep and suggest mitigating measures.

Though this committee couldn’t pinpoint the exact reasons for slope creep, it made several clear-cut recommendations to protect the area. The chief among them were:

- Complete ban on excavating boulders either by digging or blasting and a ban on felling trees, besides undertaking extensive plantation work in the area between Marwari and Joshimath and sealing of the cracks and fissures.

- Providing supports to hanging boulders at the foot of the hill on which Joshimath rests and undertaking largescale scouring or river taming measures by using concrete blocks to prevent toe cutting of the spur, especially in the Dhauliganga gorge.

- Imposing a complete ban on the collection of construction material in a five-kilometre radius of Joshimath.

- Pausing all construction activity until a detailed geological study is completed and ban on slope excavation.

- Construction of pucca (impermeable) drains carrying wastewater and closing all soak-pits and replacing them with a sewage system.

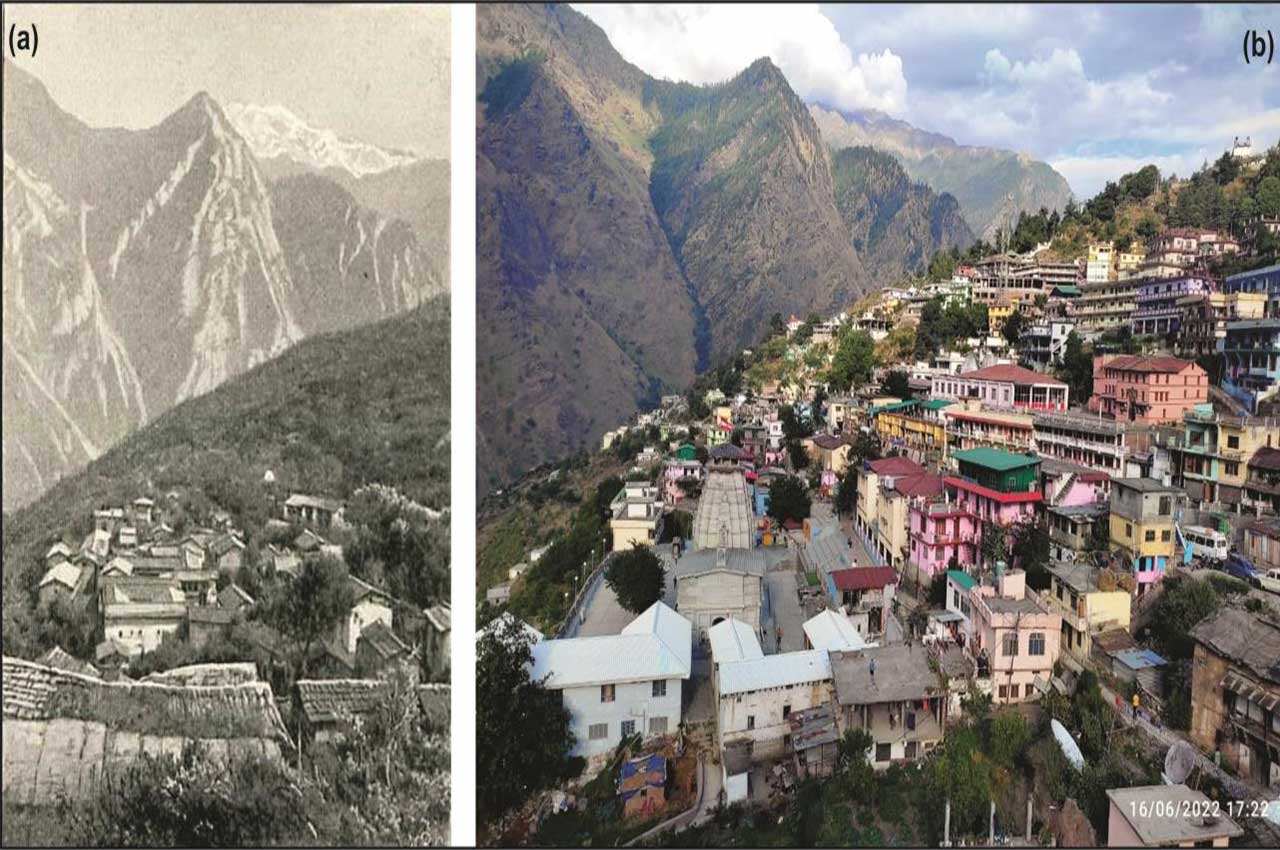

Unfortunately, most of these recommendations remained on paper. The town continued to expand in an unplanned manner (see picture). Utter disregard for the warning against boulder extraction for the construction of mega hydropower projects became the order of the day while chasing the rainbow of development. No river taming measures were undertaken in the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda gorges, despite both rivers having a long history of causing massive toe cutting of the spur over decades.

The construction of the Joshimath bypass from Helang as part of the 825-km Char Dham Yatra road project is passing through the precise vulnerable area which the Mishra Commission Report had red-flagged

Now, the construction of the Joshimath bypass from Helang as part of the 825-km Char Dham Yatra road widening project is passing through the precise vulnerable area which the Mishra Commission Report had red-flagged in 1976. This is one project on which Prime Minister Narendra Modi has staked considerable political capital, after he announced in 2016 the widening of the road corridor connecting the four religious sites (dhams)—Gangotri, Yamunotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath—at an election rally in Uttarakhand. Following the PM’s announcement, environmental groups and activists filed a number of petitions, highlighting the risks and dangers that the road widening project posed to the environment and local people.

On December 14, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled against a clutch of petitions filed by the Dehradun-based Citizens for Green Doon & Others that opposed the widening of 825 km of highways to 10 metres with a paved shoulder on the grounds of addressing national security imperatives. Curiously, the Char Dham Yatra road widening project started as a tourism project and morphed into a national security project in 2020 to ease the travel and transportation of armed forces and defence equipment to bases in Uttarakhand. Joshimath is one of the most important bases in the state for servicing defence needs on the India-China border beyond Mana village towards Niti Pass and Mana Pass.

In 2019, during the course of the hearings, the High-Powered Committee (HPC) was set up under the chairmanship of Chopra at the direction of the SC to study the impact of the project, provide recommendations and oversee adherence to environmental norms. However, Chopra resigned from the committee in a huff in February 2022, after a bench headed by the current Chief Justice of India, then Justice, D.Y. Chandrachud, accepted the arguments of the Ministry of Roads, Highways and Transport (MoRTH) for road widening in its December 2021 order. It also handed over the oversight work of the three highways of ‘strategic importance’—Rishikesh-Gangotri, Rishikesh-Mana and Tanakpur-Pithoragarh—to a committee headed by retired Justice A.K. Sikri. The HPC mandate was reduced to just two non-defence roads: Rudraprayag-Kedarnath and Dharasu-Janki Chatti.

The HPC in its interim and final reports highlighted the MoRTH’s chicanery to circumvent the mandatory Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) requirement for large infrastructure projects

“As elaborated in the HPC final report of 13.07.2020, the directions and recommendation made by the HPC in the past have either been ignored or tardily responded to by MoRTH. This experience does not inspire confidence that the response of MoRTH will be much different in relation to the two non-defence roads. In the circumstances, I do not see any purpose in continuing to head the HPC or indeed, even to be a part of it,” wrote Chopra in his resignation letter to the SC.

The HPC in its interim and final reports highlighted the MoRTH’s chicanery to circumvent the mandatory Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) requirement for large infrastructure projects. It deployed the clever ploy of splitting the Char Dham Yatra road project into 53 smaller projects, each less than 100 km, for which EIA is not required.

A task force constituted under G.B. Mukherjee, secretary, Tribal Affairs, in 2008 to study the impact of climate change in the Indian Himalayan Region in its 2010 report too echoed the recommendations of the Mishra Commission. “No construction should be undertaken in areas having slope above 30O or areas which fall in hazardous zones or areas falling on spring and aquifer lines and first order streams,” it said.

The task force further recommended that, instead of commissioning individual EIAs on a project-to-project basis, a comprehensive plan should be formulated for conducting a holistic study of the Himalayan ecosystem. “A new perspective to replace the practice of project-based environmental impact assessment (EIA), with Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) needs to be introduced.” The report underlined the “urgent need for a region and entire basin-based Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) rather than individual project-oriented Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) that neglect the summation effect”. In 2013, an Inter-Ministerial Group (IMG) headed by the then Planning Commission member, B.K. Chaturvedi, in its report on the seasonal flow of the Ganga, recommended that seven tributaries of the Ganga in the Himalaya, including the Rishi Ganga and Dhauliganga, be left untouched. The Expert Body report of 2013 also recommended leaving the area north of the MCT undisturbed for being an unstable para-glacial zone and prone to cloudbursts.

In 2014, the SC accepted the recommendations of the EB report that identified the ecological harm posed by 24 hydro-electric projects in the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi basins and ordered a stay on further work. “Given the massive scale of construction of HEPs in Uttarakhand it may be worthwhile to set up a formal institution or mechanism for investigating and redressing complaints about damages to social infrastructure. The functioning of such an institution can be funded by a small cess imposed on the developers. It is also suggested that to minimize complaints of bias, investigations should be carried out by joint committees of subject experts and the community.” The report also recommended alternative methods of road construction in eco-sensitive zones.

On ever-increasing urbanisation, the EB warned that “concentration of large populations within an urban conglomeration may have unforeseen consequences—if there are natural disasters”. The present crisis in Joshimath is also a manifestation of this socio-economic problem, but it’s not unique to this place. Most of the Himalayan towns suffer from over-urbanisation and lack of civic infrastructure. To counter it, the EB recommended policy-driven initiatives that would boost small-scale economic activity in villages and devolution of power to local bodies like panchayats and mahila mandals (women’s collectives), among other initiatives.

Riddled with mishaps, always controversial

When viewed through the filter of multiple expert opinions and analysis in these reports, it’s fairly clear that land subsidence in Joshimath, to use a cliché, was a disaster waiting to happen. The Tapovan-Vishnugad project has courted opposition and controversy right from its inception. The EIA for the project was undertaken by Wepcos Ltd., a public sector undertaking, but its report is not in the public domain.

“On August 13, 2004, NTPC held a public meeting, which was supposedly meant to address the concerns of the people of Joshimath and neighbouring villages. But the contents of the EIA report were not made available to anyone prior to the meeting,” says Atul. “Still, we participated and asked the officials on what basis the project was planned; whether there was any updated river flow, glacial melt, or sedimentation data available, or any other data that challenged the findings of the Mishra Commission…they could not provide any answers to our questions. It was clear that the public meeting was pointless and a sham.”Atul also alleges that most of the gram pradhans (elected headmen of villages), who either belonged to the BJP or Congress, except one Dharam Singh Rana of Lata village who belonged to the CPI, signed their consent under pressure from state government and NTPC officials. This paved the way for the project.

Scraps of information about the EIA available in the public domain come from various secondary sources. One such document is a summary EIA (SEIA) submitted to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2007. According to the abridged report, the project was classified in Category A “because the substantially reduced river flows will result in degradation in the river section between the weir (barrage) and tail race outlet”, resulting in reduced flow over an 18-km section. It also states that tunnelling work would result in excavation of 3.1 million cubic metres of debris, out of which only 900,000 cubic metres would be utilised for construction work. The rest of the construction material would be excavated from nearby government-approved sites. It’s clear even from the sparse SEIA that the project resulted in major geological disturbances in an area that had been clearly red-flagged by the Mishra Commission in 1976. It also did not conform to the recommendations of reports that were released in later years.

Accidents have been a regular feature since construction work started in November 2006. The initial project outlay was ₹2,978 crore. According to a research paper titled Change in Hydraulic Properties of Rock Mass Due to Tunnelling, published by Bernard Millen, Giorgio Höfer-Öllinger, and Johann Brandl, on December 24, 2009 the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) got trapped 900 metres below the surface at a distance of 3,016 metres from the mouth of the tunnel (chainage) while passing through a steep fault zone and punctured a water bearing layer (hydro strata), causing water to gush in at the rate of 700 litres per second. According to activists, the water flow has still not stopped, though it has reduced.

This incident was widely reported in the local press and caused an uproar in Joshimath. But there were two more incidents of TBM trapping that went under-reported. The second and third incidents occurred in rapid succession in February and October 2012 at chainage 5,840 metres and 5,859 metres—at a distance of barely 19 metres. In both cases, the TBM got jammed 700 metres below the surface and water gushed in yet again.

The authors of the paper also state that excavation for building the Tapovan-Vishnugad HRT caused largescale changes to the hydraulic properties of the rock mass surrounding the tunnel. “The changes occurred in high stress fields and effected rapid and largescale deformation or relaxation (>100 mm) in sections of (heavily) jointed rock mass and fault zones surrounding the TBM,” wrote Millen et al, in unambiguous terms. In simple terms, the surrounding area outside the tunnel was also impacted, which obviously includes Joshimath.

The location of the barrage is such that it has been prone to natural disasters and has taken a heavy toll of human life. The South Asia Network of Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) has listed 17 instances until now

These findings blow holes in NTPC’s assertion that the Tapovan-Vishugad project has not impacted the geological characteristics of the area around Joshimath. These TBM trapping incidents, activists and locals say, prove their allegation that no proper geological and geomorphological studies were carried out as part of the EIA.

The location of the barrage is such that it has been prone to natural disasters and taken a heavy toll of human life over the years. The South Asia Network of Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) has listed 17 instances until now when this project came under the cloud either due to mishaps, natural disasters, and gross violation of environmental regulations by the contractors.

In the June 16, 2013, Uttarakhand flash floods, which claimed more than 6,000 lives, both the diversion tunnel and diversion dyke suffered extensive damage. The barrage of the Jaypee Vishnuprayag project gave way, sending a huge volume of water downstream into already swollen rivers. Following the incident, the lead contractors for tunnelling, L&T and Alpine Mayreder, pulled out, citing safety reasons. However, it is common knowledge among environmental scientists who have worked in the region that the real reason for the lead contractors pulling out was that NTPC allegedly furnished incorrect geological data at the time of signing the contract. Investigation by scientists commissioned by L&T revealed that the area was unsafe for tunnelling and that was the reason for TBMs getting trapped repeatedly. The dispute between NTPC and L&T, though it reached the courts, was eventually resolved in an out-of-court settlement.

In February 2021, the project was hit by yet another disaster. This time the damage was more extensive. On February 7, a glacier outburst was recorded in the Nanda Devi biosphere, close to the source of the Rishi Ganga at over 4,000 metres which drains into the Dhauliganga just below Reini village. There are many competing theories as to what precipitated the glacier outburst. But the outcome was that a massive volume of ice, snow, water, boulders, rocks, and silt came crashing down the Rishi Ganga gorge, blowing everything in its path, including the 13.5 MW Rishi Ganga hydro-electric project.

Approximately 200 people lost their lives in a matter of a few hours. They were mostly workers stationed at the two project sites. NTPC faced severe criticism for its inept post-disaster handling

Then this rampaging slurry turned north, crashing into the Tapovan-Vishnugad barrage. The volume of the slurry was so large that it entered the diversion tunnel (see picture) in which construction workers were going about their jobs at the time. Approximately 200 people lost their lives in a matter of a few hours. They were mostly workers stationed at the two project sites. NTPC faced severe criticism for its inept post-disaster handling. They claimed that the surge was so fast and sudden that their early warning system failed. NTPC’s several claims, however, were comprehensively rebutted by eyewitness statements and local official accounts.

NTPC claimed to have suffered damage worth ₹1,500 crore after the Rishi Ganga flash flood. By 2014, the cost of the project overshot from an intial outlay of ₹2,978 crore to ₹3,846 crore. News reports indicate now the cost has shot up to ₹13,000 crore after factoring in damages and delays, seriously affecting the project’s viability.

Over the years, India’s biggest public sector power producer lost complete credibility with the people in and around Joshimath. It is the main reason that now the townspeople hold NTPC responsible for triggering land subsidence and slope creep. Simple posters with #NTPCGoBack have been pasted all over the town even as people sit in protest to have the company, state government and local administration held to account.

The extent to which the governing arms of Indian democracy have become dysfunctional can be gauged from the fate of a public interest litigation (PIL) that was filed in the Uttarakhand High Court after the Rishi Ganga flash flood. On July 13, 2021, one Sangram Singh of Reini village, Atul Sati, and three other activists registered a PIL in the top court of the state. They prayed that all permissions granted to the Rishi Ganga and Tapovan Vishnugad projects prior to February 2021 be cancelled; NTPC be directed to pay compensation to the affected people; proper rehabilitation be undertaken for the people of Reini; and conservation and ecological restoration work be taken up in the area.

A day later, on July 14, 2021, a bench of the Chief Justice of Uttarakhand High Court, Raghavendra Singh Chauhan, and Justice Alok Kumar Verma dismissed the PIL in its first sitting. “This petition seems to be highly motivated petition which has been filed at the behest of an unknown person or entity. The unknown person or entity is merely using the petitioners as a front (sic). Therefore, the petitioners are merely puppets at the hands of an unknown puppeteer,” said the order. Terming the petition a misuse of the PIL tool, the court imposed a penalty of ₹10,000 on the petitioners. “The court in its order said we did not provide any evidence of being ‘social activists’. But the fact is the petition was supported by 120 pages of annexures with details backed with data,” says Atul. They have filed an SLP in the Supreme Court challenging the Uttarakhand HC order.

The extent to which the governing arms of Indian democracy have become dysfunctional can be gauged from the fate of a public interest litigation (PIL) that was filed in the Uttarakhand High Court

Ostrich syndrome

In keeping with contemporary India, where the new normal appears to be suppression of information and data, the government’s handling of the unfolding disaster in Joshimath has been opaque. The agencies that have been deployed to ascertain the reasons for slope creep and subsidence have been gagged into silence. From ISRO data—which was yanked off the public platform—it was clear that subsidence was already on, starting April 2022. Between April and November, the affected area sank by 8.9 cm over seven months, which works out to an average of 1.27 cm per month. Then, in a matter of 12 days, the area saw rapid subsidence of 5.4 cm. “A subsidence zone resembling a generic landslide shape was identified (tapered top and fanning out at base). Crown of the subsidence is located near Joshimath-Auli road at a height of 2180 m,” said NRSC.

This data matches with eyewitness accounts. “In May 2022, we observed water seeping through the ground in several places and soon after cracks started appearing in the houses,” says Bharat Singh Kunwar, a veteran activist who took part in Uttarakhand’s statehood agitation in the 1990s. It was brought to the notice of the local administration. Witnessing inaction on the part of the administration, in June the people of Joshimath and JBSS requested S.P. Sati and his team to conduct a study on their behalf. Their report said that determining the cause of subsidence would require deeper research. “The existing studies pertaining to the geological setting and ecological diversity around Joshimath are fragmentary in nature thus require an integrated approach with emphasis on terrain stability and natural resource management. Specifically, a detailed multi-temporal mapping (multi-decadal) of geological, geophysical, ecological, and anthropogenic intervention at cadastral level should be carried out,” it said.

Pertinently, the observations on the road widening and building of the Helang bypass are cautionary. “However, while widening the road we must keep in mind that as we climb up from Helong the road stretch between Sailang and Paini which passes through the old landslide deposits is subsiding at multiple places,” it said.

This report galvanised the state government to commission its own study, headed by Piyoosh Rautela, executive director, Uttarakhand State Disaster Management Authority (USDMA). The 27-page report submitted in September 2022 contained a host of recommendations but remained conspicuously silent on the impact of three large hydropower projects surrounding Joshimath, impact of tunnelling on rock mass, and on repeated disasters and accidents that have hit the Tapovan-Vishnugad project. Nor does it talk about crude methods like dynamite blasting and rock cutting for road widening and building the Helang bypass. The USDMA report is bereft of any new geological data, except for recycling some of the findings of previous reports.

Instead, the report by the five-member SDMA committee recommends a host of plausible mitigating steps such as managing pore pressure, drainage improvement, implementing building byelaws, and so on. In one instance, it says that some of the houses developed cracks because they lacked a foundation! “At many places, the houses are observed to be constructed without adequate support of the foundation. In some cases, foundation is observed to be absent. In other cases, the foundation is not supported by retainingwalls,” says the report. On managing pore pressure, it recommended making all uncovered surfaces impermeable. “All open surfaces be therefore identified and made impervious by providing a layer of rammed clay on these,” it says.

In comparison to the near-unanimous conclusions and recommendations in more than half a dozen other reports, the SDMA document reads like a deflection operation for failing to monitor large infrastructure projects like hydropower projects and the Char Dham Yatra road widening.

Interestingly, in May 2010, when Rautela was still teaching in HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar, he co-authored a paper with M.P.S. Bisht which was published in Current Science journal. This paper was published a year after the first incident of TBM trapping in 2009. “It is interesting to note that a private company was preferred by National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) over the Geological Survey of India, for undertaking geological investigations related with the project. These investigations failed to take cognizance of the earlier geological investigations carried out in the area and did nothing to establish the depth of overburden all through the tunnel alignment,” Rautela and Bisht wrote. This observation is exactly what the activists and townspeople have been accusing the NTPC of for a long time.

The authors also note that puncturing of the hydro strata could lead to subsidence. “This sudden and largescale dewatering of the strata has the potential of initiating ground subsidence in the region.” They conclude by saying, “It is too early to foresee the full long-term implications of this event, but these are sure to be serious. This is a clear case of negligence on the part of the agency undertaking the exploration in this sensitive zone. It calls for stringent compliance of the preliminary investigations together with harsh punitive measures for the ones who fail to comply.” That the opinion of the same person would differ so wildly in a span of 12 years is intriguing.

According to Uttarakhand government data, the secondary sector comprising electricity, gas, water and other utility services contributed 44.85% to the Gross State Domestic Production in 2019-20

Uncertain fate

What lies in store in the coming days, months and years is unknown, even as more houses and roads develop cracks. How long the town that came up around the 13th century temple of Jyotir Math that embodies the legacy of Adi Shankaracharya, from which it derives its name and because of which it is one of the holy peeths (temporal seats) of Hinduism, will survive is at the moment uncertain. But what is certain is that circumstances are primed for a major calamity.

Kunwar, now in his sixties, has witnessed Uttarakhand’s formation, evolution and degradation over the past two decades. “When the state was formed, the people of Uttarakhand had big dreams. They wanted to script their own future and prosperity,” he says, sitting beside a fire on a cold and wet evening outside his dhaba in Helang. “But the way the so-called development of the state unfolded is not only tragic, it’s also devastating. Politicians of both the BJP and Congress, who have ruled the state at various times, saw our rivers, forests and mountains as an easy source of money. It’s their greed that has brought us to this precipice, and the people played along. Building hydropower projects and dams has become an epidemic disease here…very little effort has been made to develop an alternative economic model, which is more environment and people friendly.”

According to Uttarakhand government data, the secondary sector comprising electricity, gas, water and other utility services contributed 44.85% to the Gross State Domestic Production (GSDP) in 2019-20. Out of this electricity generation contributed a whopping 74% to the secondary sector basket. It’s clear where the state’s priority lies. The rivers are seen as a veritable golden goose. As for the people and the environment, they are headed for doom. But who cares, except that the Joshimath story is a warning foretold, especially for Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and other hill states, which too have hitched their wagons to the hydropower gravy train.

With additional inputs from Jasvinder Sidhu