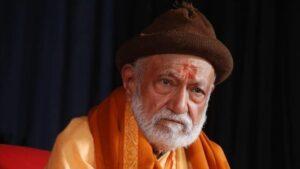

Magsaysay Award Winner Dr. Rajendra Singh—revered as India’s “Waterman” for his five decades of work in reviving rivers—has called for urgent recognition of rivers as legal persons. In India’s cultural tradition, rivers have long been revered as mothers, worshipped and protected well before the law ever acknowledged such rights. But today, he laments, sacred ghats have been commercialized, and rivers have been reduced from Mai (mother) to kamai (a means of earning). Many are now little more than waste channels, in danger of running dry unless immediate, decisive action is taken.

In an interview with Tatsat Chronicle, Dr. Singh recalled the landmark 2017 judgment of the Uttarakhand High Court, which declared the Ganga and Yamuna legal persons with rights akin to those of humans—a bold attempt to save rivers “losing their very existence.” The ruling was quickly stayed by the Supreme Court, but environmentalists saw it as an urgent corrective to decades of river diversion for irrigation and hydropower, which have depleted flows and eroded groundwater recharge.

Eight years later, no government has implemented or even examined the idea, despite the judgment drawing international attention and often being cited alongside New Zealand’s groundbreaking law granting legal personhood to the Whanganui River. The missed opportunity speaks volumes about political priorities and the inertia of environmental governance.

A Global Crisis of Flow

While global experience with granting legal personhood to rivers is limited, the urgency of such measures is hard to ignore. Human activity—industrial waste dumping, dam construction, and aggressive river diversion—has pushed the world’s waterways to a breaking point. Only 21 rivers longer than 1,000 kilometres now remain undammed, still connected to the sea.

According to International Rivers, a global non-profit, more than 58,500 large dams currently block 67 percent of the planet’s rivers, undermining biodiversity, threatening livelihoods for millions, and destabilizing the deltas that shield coastlines from erosion. In many cultures, the loss of a free-flowing river is regarded as a cultural and ecological calamity.

This is where the “Rights of Nature” approach gains urgency. At its core, it rejects the notion that nature is merely property for human exploitation. Instead, it recognizes that ecosystems possess inherent rights to exist, thrive, and regenerate. By rewriting legal systems to serve the environment rather than harm it, this framework directly addresses the persistent failures of modern environmental law.

Guardians for the Voiceless

For centuries, the natural environment has been governed under a property-based legal regime, leaving rivers and other natural features without legal identity or agency. “The laws we have are not rising to the threats we face,” warns Monti Aguirre, Latin America Coordinator at International Rivers. “Legal structures that treat rivers and nature as an object for human exploitation are enabling today’s crises. A Rights of Nature approach offers transformative change at a time where it could not be needed more.”

Narendra Chugh of the Pune-based Jal Biradari shares this view with Aguirre. “Rivers can’t express themselves,” he says. “They need a guardian to look after their interests.” Chugh believes that recognizing rivers as legal persons would impose accountability and empower courts to protect them. The Uttarakhand High Court attempted exactly that in 2017, naming the Director of Namami Gange, along with the state’s chief secretary and advocate general, as guardians—or “the human face to protect, conserve, and preserve” the Ganga and Yamuna.

But the state resisted. In its appeal to the Supreme Court, the Uttarakhand government argued that its chief secretary and advocate general could not shoulder such responsibility because the Ganga flows through multiple states. This overlooked the fact that the Namami Gange Director—whose jurisdiction spans state borders—was also named a guardian. Chugh was blunt: “How can they agree to be guardians when these are the very people exploiting the soul of the river?”

The Choice Before Us

The debate is no longer about whether rivers need protection—it is about whether our legal and political systems are willing to acknowledge their right to survive. Legal personhood is not a symbolic gesture; it is a structural change that shifts the burden of proof from those defending rivers to those seeking to exploit them.

In the end, Dr. Singh’s plea is as much about law as it is about values. If India—and the world—fail to give rivers a voice in the legal system, they will continue to be treated as lifeless commodities, until they are lifeless in fact.

A Global Movement Finds Its Voice

The Rights of Nature approach is gaining momentum across continents—from the Americas and Oceania to Africa and Asia. In New Zealand, known by its Māori name of Aotearoa, the concept found expression in legislation rather than judicial pronouncements. Rooted in the indigenous principle of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship—where humans are stewards, not owners, of the natural world—this philosophy was enshrined in law as early as 1990.

Since then, the New Zealand Parliament has passed two landmark laws: the Te Urewera Act of 2014, recognizing a national park as a legal person, and the Whanganui River Settlement Act of 2017, granting the same status to the Whanganui River. These were not symbolic gestures but legal commitments to protect ecosystems as living entities with rights.

Dr. Rajendra Singh, who heads the voluntary organization Tarun Bharat Sangh, praised the New Zealand model but expressed little hope that such laws would take root in India—despite their deep resonance with the country’s cultural and spiritual traditions. “In India, people hold the Ganga as holy, yet treat it like a garbage truck,” he said, citing the government’s inaction even after environmentalist and engineer Guru Das Agrawal died in 2018 following a 111-day fast to demand the river’s cleanup.

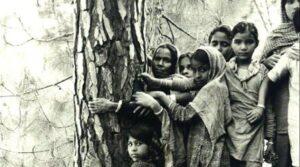

India’s history, ironically, includes one of the world’s most influential environmental movements: the Chipko, or “tree-hugging,” movement of the 1970s in the Himalayas. Rooted in the kinship between people and nature, Chipko inspired global campaigns against deforestation, noted for its non-violence and the active involvement of women, tribal communities, and local residents. Yet, decades later, the political will to protect rivers in the same spirit appears elusive.

Defining Rights for Rivers

The push for Rights of Nature intensified in 2017, the same year as the Whanganui River legislation, when river advocacy groups Earth Law Center and International Rivers drafted the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Rivers. Modelled on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it declared rivers to be living entities and enumerated six fundamental rights: the right to flow; the right to perform essential ecosystem functions; the right to be free from pollution; the right to feed and be fed by sustainable aquifers; the right to native biodiversity; and the right to regeneration and restoration.

The declaration also sounded an alarm over escalating threats: pollution, excessive water diversion, and physical alterations from dams and other infrastructure. Such measures, while profitable for some, face strong opposition from vested interests wary of restrictions on dam and barrage construction. Farmers reliant on canal irrigation—particularly for water-intensive crops like rice and sugarcane—also fear the economic impact of limiting river diversions.

The Indian Legal Dilemma

Asim Sarode, former president of the NGT Lawyers Association, called the 2017 Uttarakhand High Court judgment pathbreaking but criticized its religious framing. “We can only succeed if the approach is scientific, like the Whanganui River Act in New Zealand,” he said. Sarode pointed out that, despite the Supreme Court stay, the judgment remains on record and could be revived if environmentalists chose to test the judiciary’s evolving attitude toward ecological protection.

He sees it as a potential starting point for a new jurisprudence based on the legal personhood of rivers and nature—an idea with precedents in international law. The Rio Declaration of 1992 established that sustainable development requires human life in “harmony with nature.” In 2009, the UN General Assembly went further, proclaiming April 22 as International Mother Earth Day, affirming the idea of nature as a rights-bearing entity.

The Rights of Nature issue also revives the debate between anthropocentrism and non-anthropocentrism that includes ecocentrism, biocentrism and even universal consideration. It poses the question – whether a forest is merely a stand of timber, a river a source of power, a quarry just a repository of stone—or whether these are integral components of a living, interdependent web that sustains both human and non-human life. The answer to that question may determine the future not just of our rivers, but of our survival.