In a striking shift, China has reportedly initiated contact with the Baloch Raji Ajoi Sangar (BRAS), a coalition of Baloch separatist groups long opposed to foreign presence in Pakistan’s restive southwest. This marks the second known instance of Beijing directly engaging with Baloch rebels — a move underscoring growing frustration with Islamabad’s failure to secure Chinese interests on the ground.

Baloch insurgents have repeatedly targeted Chinese personnel and infrastructure tied to the multibillion-dollar China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the crown jewel of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative in South Asia. As attacks have intensified, so too has China’s pressure on Pakistan.

The tone was unmistakable in a recent editorial published by the Global Times, a Chinese state-run outlet, during Pakistani Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar’s visit to Beijing. The article noted bluntly: “The CPEC, as a major cooperation project, still faces various risks such as the threat of terrorism. Eliminating these threats has become an urgent issue for Pakistan.”

By reaching out to insurgents once deemed untouchable, Beijing may be signalling a more pragmatic — and more transactional — approach to protecting its strategic foothold in the region.

China’s Balochistan Dilemma; China is angry with Pakistan

China is growing visibly frustrated with Pakistan’s inability to contain the long-running insurgency in Balochistan — a conflict that now threatens the future of the flagship China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). As attacks on Chinese assets and personnel escalate, Beijing is increasingly questioning the reliability of its partner in Islamabad. This raises the question as to the importance of Balochistan in CPEC’s scheme of things and how China intends to monetize its investments on ground.

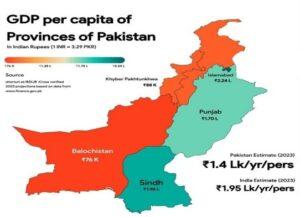

At the heart of this tension lies Balochistan — Pakistan’s largest province by land, yet among its poorest by income. Despite its wealth of natural resources, the province remains economically marginalized. Per capita income hovers below $1,000, while large-scale infrastructure and mining projects primarily benefit external actors, most notably China.

CPEC, a cornerstone of President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, was envisioned as a transformative economic corridor linking western China to the Arabian Sea via Pakistan’s Gwadar Port. But the spoils of development, including lucrative contracts in mining and transport, have largely bypassed local communities. In Balochistan, this has deepened resentment and fuelled the very insurgency China now fears.

Behind Beijing’s public calls for security lies a more fundamental concern: how to secure returns on billions of dollars invested in a region slipping further from Pakistan’s control. For China, the math is simple — infrastructure must yield dividends. But for Pakistan, the political costs of those dividends are mounting fast.

The question now is not just whether CPEC can survive Balochistan’s unrest — but whether Beijing’s patience with its partner is wearing dangerously thin.

Follow the Money: How China Profits from CPEC in Balochistan

Notably, China’s investment in Balochistan is important to the CPEC, as approximately 90% of the investment is concentrated in the Gwadar region aimed at improving the performance of Port Gwadar.

At its core, monetizing Chinese investments in Balochistan — particularly through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — is a closed financial loop: Chinese capital flows to Chinese state-owned firms, which build infrastructure in Pakistan, and the resulting profits are largely repatriated to China.

While CPEC aims to boost Pakistan’s economy and provide China with strategic advantages, security threats, deep-seated local grievances, and inequitable resource distribution have stalled progress and intensified resistance. Also, while CPEC is often framed as a win-win for both nations, in practice, the economic benefits have been uneven. For Beijing, this growing instability undercuts both its economic returns and strategic ambitions — and fuels its mounting frustration with Islamabad.

Monetization of Chinese investments in Balochistan

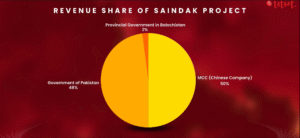

The example of the Saindak Copper-Gold mine is a telling example of the process of extraction of profits. In 2021 alone, the Chinese company operating the mine reportedly made a profit of US$ 75 million. Most of it repatriated to China, with negligible benefits reaching the local population.

The pattern seen at Saindak echoes across CPEC projects where Beijing has invested in Balochistan: economic activity driven by foreign capital, managed by foreign companies, and yielding foreign profits. Most investments in Balochistan are largely concentrated in the Gwadar region to increase Gwadar Port’s commercial viability. Pakistan hosts atleast 16 CPEC projects, including Gwadar Free Zone and Gwadar Power Plant. Initially launched in 1995 as a joint venture between Pakistan’s state-owned Saindak Metals Ltd. and China’s Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC), the project was valued at $350 million and leased to MCC for 10 years. Under the original terms, MCC received 50% of the revenue, the Government of Pakistan 48%, and the provincial government in Balochistan received just 2%. The lease was later extended, with Pakistan’s share of revenue going up to 53%, and Balochistan provincial government’s share increased to 6.5% — a symbolic increase; critics argue, given the scale of mineral wealth extracted. Beyond profits, the raw copper extracted from Saindak is exported almost entirely to China. According to sources, copper exports from the mine reportedly surpassed $1 billion in the first eleven months of 2023 — yet the region remains plagued by poverty, underdevelopment, and resentment.

CPEC’s Hidden Ledger: Who Really Profits in Balochistan?

The Gwadar Port in Balochistan, a flagship project of CPEC, is another example of Chinese investment in the province. The Port aims to connect China with the Arabian Sea. The Port offers China an alternative energy route to the Malacca Strait, where 80% of China’s oil imports pass through.

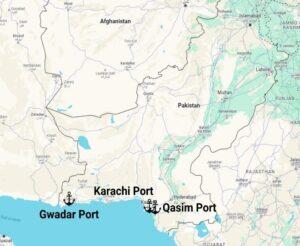

Pakistan has three main international ports, namely Karachi Port, Qasim Port, and Gwadar Port. Despite years of fanfare and billions in investment, Gwadar Port remains an underperforming node in Pakistan’s maritime network. According to Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance, the port handled a mere 34,000 tonnes of cargo in the 2023–2024 fiscal year — a figure dwarfed by the 64 million tonnes managed by Karachi Port and 34 million tonnes by Port Qasim.

This stark underperformance underscores Gwadar’s lack of commercial viability — but also highlights the deeper strategic rationale behind China’s investment. While trade volumes remain minimal, the long-term calculus appears military. In time, it is plausible that Chinese naval vessels will use the port for logistical turnaround and operational support, anchoring Beijing’s presence in the Arabian Sea under the guise of economic development.

There is no doubt about the immense geostrategic value of Gwadar, due to its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz. By securing control over Gwadar, China gains direct access to the Arabian Sea. However, the challenge is that China gets the lion’s share of all the profits from CPEC investments. With the Gwadar port, for instance, 90% of the limited revenue goes to the Chinese operating company. The Pakistani government receives only 10%, while nothing goes to the Balochi regional government.

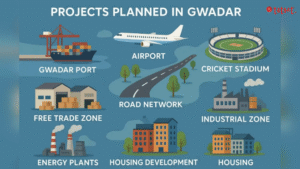

In a gesture framed as economic goodwill, China announced in August 2015 that it would convert previously approved concessionary loans for Gwadar-based projects — totalling $757 million — into interest-free loans. Thus, Pakistan would only have to repay the principal value. While touted as evidence of Beijing’s commitment to Pakistan’s development, critics argue it was a calculated move to tighten strategic influence under the veneer of financial generosity.

Projects being financed by these loans include: installation of breakwaters in Gwadar costing US$ 130 million, a US$ 360 million coal power plant in Gwadar, a US$ 27 million project to dredge berths in Gwadar harbor; construction of the US$ 140 million East Bay Expressway project; and a US$ 100 million 300-bed hospital in Gwadar. But the situation gets even more piquant. Constructed with a US$ 230 million Chinese grant, the opening of New Gwadar International Airport suffered several delays prior to its soft launch in early 2025. It is Pakistan’s largest airport by area, and built near Gwadar port, also remains largely unused. As per an agreement between Pakistan and China, 91% of the revenue generated by Gwadar Port will go to China Overseas Ports Holding Company and 9% to Gwadar Port Authority. In March 2019, Pakistan’s Senate was informed that in the last three years, total gross revenue of Pak Rs 358.151 million had been generated from Gwadar Port, out of which Gwadar Port Authority received only Pak Rs 32.324 million.

China Builds, China Gains — Balochistan Gets Left Behind

The challenge for Pakistan from Chinese CPEC investments – the government in Islamabad accepted sovereign guarantees at high rates on Chinese investments but rarely found the money entering their financial system. Chinese funds mostly went from Chinese financial institutions to Chinese companies that built the infrastructure in Pakistan mainly Balochistan. Further, the Pakistani State still has the responsibility of paying back the loans and/or the sovereign guarantees. Uncertainty over the political situation and security situation ultimately convinced the Chinese to slow down their investments in Pakistan.

The above narrative amply demonstrates the reasons why Balochistan remains an area of interest for China. It is about extracting the region’s natural resources and taking away all the profits from the investments, be it in the field of energy, infrastructure or even ports. That is the harsh reality of Chinese investments in Pakistan and more specifically, Balochistan.