Come February 2022 and the 21-year-old Himalayan state of Uttarakhand will be plunged into yet another Assembly election amidst increasing voter apathy. The question is, what will those lining up at the polling booths in wintry conditions get in return for their vote?

The state, carved out of Uttar Pradesh in 2000 after a prolonged struggle led mostly by women has seen 11 chief ministers come and go in 21 years. The longest tenure was that of Congress stalwart Narain Dutt Tewari who, ironically, was credited with the slogan, “Uttarakhand will be formed over my dead body.”

Nityanand Swami of the BJP took office in November 2000 and took major decisions like setting up of a new capital and a high court, keeping in mind the traditional rivalry between Garhwal and Kumaon. And since the capital, Dehradun, was in Garhwal, the high court was set up in Kumaon.

Right from the start, the stars seemed to be conspiring against Uttarakhand as instability hit the Swami government from the first day itself with some ministers refusing to take the oath of office but relenting later. Still, within a year, the ‘gentlemanly’ Swami’s tenure was cut short by a revolt of BJP MLAs and Bhagat Singh Koshyari took charge in October 2001. This mid-term change of horses that had failed in Delhi and elsewhere failed here too as the BJP lost the first election in Uttarakhand in 2002 and N.D. Tewari was anointed chief minister.

This was unfair as the Congress had won the battle under the leadership of Harish Rawat, a tough leader with a strong base in the party’s Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC) and Seva Dal. But insider manipulations and string-pulling by Satpal Maharaj put Tewari on the throne. Looking at today’s short-cut seeking Congress leaders, it is important to remember that Rawat not only agreed to the high command decision but remains in the Congress till date, never wavering in his loyalty to the party.

Merry-go-round

Merry-go-round

Since then the state has seen the BJP and Congress coming to power alternately and infighting, especially in the BJP, that has resulted in several faces like Ramesh Pokhriyal Nishank, Koshyari, B.C. Khanduri (twice), Trivendra Singh Rawat, Tirath Singh Rawat and now Pushkar Singh Dhami occupying the chief minister’s chair. It must be admitted that these leaders have been honest to a fault and have never hesitated in levelling corruption charges against their own partymen!

But where does this merry-go-round take Uttarakhand, reverentially called Dev Bhoomi? Literally in circles and leading nowhere.

Having watched the growth of the state from its infancy (I was there as the first Hindustan Times correspondent in 2000) to an adult of 21, and speaking to various stakeholders, one inevitable conclusion is that the basic problems the state was born with remain as they were. Some have only become worse because the politicians have no solutions, and the bureaucrats are a happy lot in the sunshine of Dehradun while the rest of India fights pollution and early morning fog.

The biggest challenge before the state remains restoration of the balance between the remote villages, some with only a few families, and those nearer the big cities-which remains unresolved, as reflected in the Election Commission’s figures from 2017.

Successive governments have failed to provide the four basic needs-employment, roads, health and education-to people, creating “ghost villages.”

Of the 70 Assembly constituencies, 12 have a population of less than 90,000. The maximum population of 1.93 lakh happens to be in Dharampur (Dehradun) and the least in Purola, 78,000 (Uttarkashi). Others in the under-90,000 category are Tehri, Dhanolti, Lansdowne, Pratap Nagar, Deoprayag, Gangotri, Gopeshwar, Kedarnath, Narendranagar and Chaubattakhal.

When the state was carved out of Uttar Pradesh, the main grouse of the people was that decisions taken in Lucknow were not percolating to the remote hill areas.

Only the names seem to have changed since then. Today, all development activities are centred around Dehradun, Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar which are in the plains while the hill areas still witness migration on a large scale.

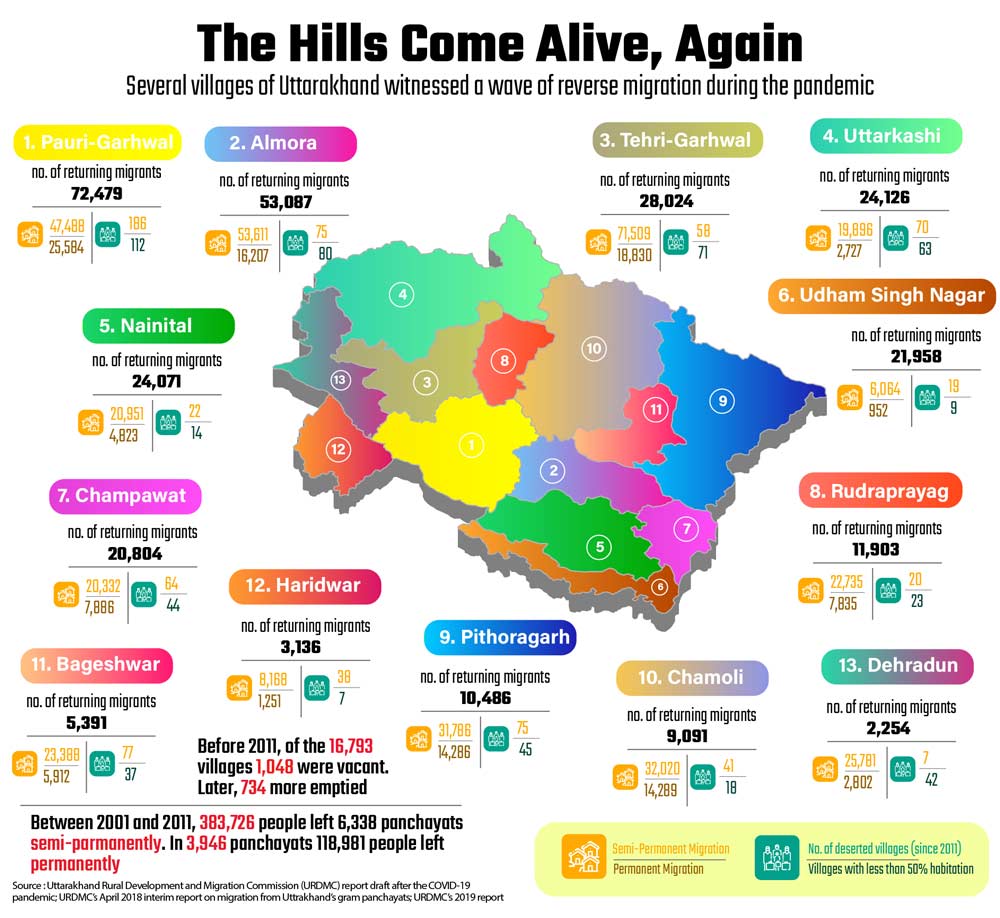

As many as 764 villages have been declared ‘ghost villages’ where no one wants to live and the recent electoral list reveals that out of 78.15 lakh voters, 3.83 lakh had left home in 2017.

Interestingly, every party with the possible exception of the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal admits that this is true, but they dismiss the issue as inconsequential. Says Harish Rawat, former chief minister and most senior Congress leader, “Migration is not bad, per se. If a qualified doctor or professional is in demand in any part of the country or the globe, no one should stop him. Yes, migration should not be due to lack of job opportunities. That has to be stopped by providing employment in the constituency itself. During my tenure the unemployment index had come down to 1.5, it has gone up to 9.5 today.”

The BJP vice-president, Dr Devendra Bhasin, who links migration to history, echoes the sentiment. “Migration and unemployment have been with us historically, even before the state was born. But migration is of two kinds, one for the opportunity of good jobs which should be welcome while the other is due to lack of employment and is something we are trying to check.”

Hanging fire

When it comes to the “other migration”-created by a lack of local opportunities-that the state’s leaders talk of so glibly, it reminds me of my first posting to Dehradun in 1998. I was shocked to hear from leaders like Suryakant Dhasmana, vice-president of the Pradesh Congress Committee now, who said youths were leaving in desperation, so much so that in several villages they could not find four youths to carry a dead body to the pyre.

Not much has changed in 21 years of statehood and leaders are least bothered because their own children are happily settled abroad.

Some side effects of this mass migration in Uttarakhand have been brought out in a paper, “Bringing Forward the Left-Behind: Impact of Male Out-migration on Women in Hill Districts of Uttarakhand”, by Prakriti Sharma, a consultant at Athena Infonomics. She uncovered some very interesting facts while working on a research paper in 2019 for TERI School of Advanced Studies.

When Uttarakhand was carved out of Uttar Pradesh, the main grouse of the people was that decisions taken in Lucknow were not percolating to the remote hill areas. The problem still exists, with Dehradun replacing Lucknow.

Talking about her study, Sharma said, “We conducted our study in four villages of Almora (but others were doing it in almost all villages of Uttarakhand) from January to May to find out how the migration of men was affecting the women who were left behind to take care of both the home and the fields.”

One determination was of course that agriculture in these villages was becoming feminine-oriented by default. Secondly, the workload of women had doubled but it was convenient for the men to let it remain so even when some of them had returned. Soorajast Pahad Mast holds as good today as it did then.

The study revealed one positive side effect of this exodus of men in that the education level of girls went up but, unfortunately, the aim was not to hike their awareness but to increase their matrimonial eligibility.

The decreasing area of agricultural land and consequent drop in agricultural produce has been another cause of worry about which this report says, “With agriculture as the primary activity of most households, 60.25% of households owned about 17,000 square feet of land or less. Out of this, 89% women did not have property rights over that land which restricted their control and ownership.”

The 2011 census report recorded that there were 968 ghost villages in Uttarakhand (a government survey in 2017 put it at 764) and about 70,000 hectares of land was non-agricultural, though unofficially the figure is said to be 1 lakh hectares.

Yet none of this seems to worry the politicians of the state, most of whom prefer to remain in Dehradun or cities like Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar. When the new state was formed all the ministers loved to be invited to programmes in Dehradun to be felicitated and the sale and prices of flowers shot up. Organisers of some programmes told journalists that if they invited two or three ministers, they got calls from others asking why they had been left out.

This is distasteful hypocrisy because when the choice of a capital for the new state was being discussed there was much talk of making Gairsain, a desolate area almost mid-way between Garhwal and Kumaon, the capital.

Nityanand Swami announced Dehradun as the ‘interim’ capital because it was the only city with good rail, road and air connectivity. However, it remains an ‘interim’ arrangement till date because no politician worth his salt dares to openly speak out against making Gairsain the state capital. Subsequent chief ministers have paid lip service to this sentiment by declaring Gairsain either as the summer capital or the winter capital.

Avadhash Kaushal, who runs an NGO called Rural Litigation Entitlement Kendra to fight for the rights of the Van Gujjars in the Rajaji National Park, says, “People are running away from the villages because successive governments have failed to provide the four basic needs-employment, roads, health and education.”

Harish Rawat, during his tenure as CM, did try to check the migration problem by empowering women. “In two years, I should be in a position to say that half the business in the state will be run by women,” he was quoted as saying in an interview. He himself was out of office in two years.

Dehradun was announced as the ‘interim’ capital, to buy time to develop Gairsain as the state capital. However, subsequent chief ministers have paid lip service to this sentiment.

Talking of his electoral plank this time, Rawat told this writer, “The economy of the state is in the doldrums, prices are at an all-time high, people’s hopes and ambitions have been crushed and there was huge corruption even during the pandemic when the testing for the coronavirus was being done. We had brought the Lokayukta to the state but it has not been implemented.”

Will Rawat be the face of the Congress in the elections?

Ganesh Godiyal, UPCC president, says, “I am not authorised to comment on this. But I can definitely say that if we come to power we will implement the programmes initiated by Harish Rawatji during his tenure.”

Refusing to comment on the frequent changes in chief ministers by the BJP in the state, Dr Devendra Bhasin, who is also the party spokesperson, takes credit for the creation of the state, revealing that a letter written by the brother of then RSS Sarsanghchalak Balasaheb Deoras demanded a separate identity for two reasons-one, that it was a state that bordered China, and, two, the hill regions were seeing no development. Both the Samajwadi Party and Congress were against the new state, he says, and adds that Uttarakhand was created by Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

Bhasin claims that the state has done very well in its battle against the coronavirus and, despite the pandemic, the employment scenario has improved. “One of the innovations the BJP has initiated is the homestay concept under which people can rent their homes in the villages to visitors and tourists who prefer these to staying in hotels. This concept is catching on and should be a great boost to the common man’s income,” he said.

But the ground reality is that the state has not moved ahead in any direction.

Poor leadership

Commenting on this, Shivanand Chamoli, one of the founding members of the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal, says, “We have not progressed because we got a third-class bureaucracy and third-class leaders imposed from Delhi. Corruption among the bureaucrats is rampant because the political leaders are illiterate and totally dependent on the bureaucracy.”

He is right to a great extent. I remember the first chief minister, Swami, saying, “I have to leave now because Tolia Saheb has called us.” R.S.Tolia was the first chief secretary of the newly formed state.

Kaushal, of the Rural Litigation Entitlement Kendra, expresses disappointment. “These politicians are a bunch of liars. They promise the moon during elections but even after 21 years the state lags behind on all the parameters of development besides employment, roads and continuing migration. People are leaving the villages more than ever before.”

Anoop Nautiyal, a Dehradun-based social activist and founder of the Social Development of Communities (SDC) Foundation who briefly dabbled in politics five years ago when he joined the Aam Aadmi Party, which has declared Col (retd) Ajay Kothiyal as its chief ministerial face in the 2022 assembly polls, makes a crucial observation. “The big change that has come about in 21 years is that while earlier leaders like Nityanand Swami were worried about being pulled up by the party high command if newspapers reported against them, today no one is bothered about what the media writes. You can sit on a dharna and even die but it does not change things one bit.”

Communication from leaders is no longer meant for the community, but is for other political parties.

Another important observation he makes is, “Communication from leaders is no longer meant for the community. Their messages are meant for other political parties and those leaders who claim they fought for the state are only raising emotive issues because they don’t know how to handle the issues of administration.”

Judging from the wind’s direction, the Congress seems to have dug in for a tough fight. Severely dented by mass desertions at one time, the Uttarakhand Pradesh Congress Committee got a major boost when one of its stalwarts, Yashpal Arya, a prominent Dalit, rejoined the party.

Godiyal, terms it ‘reverse migration’ and says it is the beginning of erstwhile Congress leaders rejoining before the elections.

Uttarakhand has seen the BJP and Congress coming to power alternately and infighting, especially in the BJP, that has resulted in several faces becoming chief minister.

He disagrees that all the problems of the state remain as they were because issues of roads, electricity and water were mostly resolved during the tenures of Congress leaders ND Tewari and Harish Rawat. “Yes, I agree that problems of employment, health and education remain to be tackled and our manifesto that is being prepared after consultations with major stakeholders will declare a major thrust on employment,” says Godiyal.

The BJP, of course, is all set to field its young chief minister, Pushkar Singh Dhami, whom even some in the opposition are secretly rooting for.

State leaders agree that problems of employment, health and education remain to be tackled in Uttarakhand.

India’s sixth-richest state in per capita income terms

Development has been somewhat lop-sided in Uttarakhand even though it is the sixth-richest state in India in terms of per capita income. While the lower reaches have seen explosive growth, the more mountainous areas have languished in comparison and agriculture continues to be a mainstay of village incomes. In fact the gap is wide between the plains areas and the hills, with the per capita income being significantly lower in the latter. Besides traditional agriculture that revolves around missed cropping, floriculture and horticulture are significant pillars of the state’s agricultural economy.

Said a Congress leader, on condition of anonymity, “If the BJP manages to stay afloat this time it will complete its five-year term. Mark my words.”

Dhami is confident of returning to power in Dehradun but he has little to show in terms of achievements other than on the basis of programmes initiated by the Centre, as opposed to results by way of his predecessors’ efforts. If they were so competent, they would not have been thrown in the dustbin, anyway.

Dhami has also said on the occasion of the state’s anniversary that he is confident of breaking the jinx about one party not winning consecutive elections. “We have road connectivity …thanks to the ambitious Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojna launched by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is taking it forward,” he told a news channel.

And then the added emphasis, as if to warn potential rivals in the party, ever ready to pull the rug from under the feet of anyone too ambitious, “I have the blessings of the top leadership-PM Narendra Modi, home minister Amit Shah and party president J.P. Nadda.”

At the recent party conclave too, Dhami spoke proudly about the work “being undertaken by the Central government in Uttarakhand” lest the credit be taken by any of his predecessors.

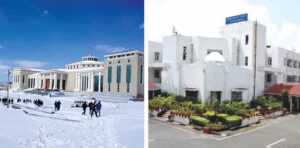

The two capitals of Uttarakhand, the new assembly building at Garsain (left) in Chamoli district up in the mountains which is

the summer capital, and the state assembly building in Dehradun. Photos: UKVIDHANSABHA.UK.GOV.INWith such credentials, it would be interesting to watch the results of this match in Uttarakhand in February between the seasoned Harish Rawat and the hard-working young Pushkar Dhami.

Uttarakhand has seen the BJP and Congress coming to power alternately and infighting, especially in the BJP, that has resulted in several faces becoming chief minister.

Successive governments have failed to provide the four basic needs-employment, roads, health and education-to people, creating “ghost villages.”

When Uttarakhand was carved out of Uttar Pradesh, the main grouse of the people was that decisions taken in Lucknow were not percolating to the remote hill areas. The problem still exists, with Dehradun replacing Lucknow.

Dehradun was announced as the ‘interim’ capital, to buy time to develop Gairsain as the state capital. However, subsequent chief ministers have paid lip service to this sentiment.

Communication from leaders is no longer meant for the community, but is for other political parties.

State leaders agree that problems of employment, health and education remain to be tackled in Uttarakhand.