First came the long-awaited extradition of Tahawwur Rana — accused of involvement in the 2008 Mumbai attacks — was extradited from the United States to face trial in India. The attacks, which left more than 160 people dead, remain one of the country’s darkest chapters.

Recently, Belgian authorities have detained Mehul Choksi, the fugitive diamond magnate accused of orchestrating one of India’s largest financial frauds. His arrest marks a significant milestone in a case that has spanned continents and tested the patience of Indian investigators.

The back-to-back developments reflect a broader shift — not only in India’s resolve to bring fugitives home, but also in its ability to build strong cases, navigate international legal systems, and mobilize diplomatic pressure when necessary.

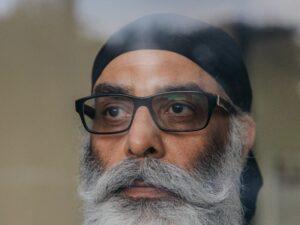

But as India demonstrates increasing reach and resolve abroad, it finds itself under scrutiny for the very tools it may be using to extend that reach. India must thank Canada for ‘revealing’ its covert action capabilities. In June 2023, the killing of Khalistani separatist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in British Columbia — initially dismissed as the result of gang violence — spiralled into a diplomatic flashpoint. Canadian authorities soon accused India’s external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), of orchestrating the assassination. What followed was a series of leaks to the press, including claims that Canadian intelligence had identified Indian officials allegedly operating undercover in Canada. Western media outlets, notably The Washington Post, seized on the revelations, casting a harsh spotlight on India’s overseas intelligence operations. Missing from much of the commentary, however, was the broader historical context: intelligence services around the world, particularly during the Cold War, have long engaged in covert actions, including targeted killings.

India, in this light, was not necessarily rewriting the rules — merely stepping into a domain long occupied by the world’s most powerful intelligence actors. For Canada, the uproar provided both justification and political cover for a sharp downturn in bilateral ties, even as it grappled with growing concerns over foreign interference on its own soil. The allegations of Indian participation of the killing of Nijjar are part of the carefully orchestrated campaign by Canada as part of its ongoing efforts to implicate (without any evidence) New Delhi’s interference in their electoral system. This is where the narrative began. However, it did not stop just there, and more articles appeared, questioning India’s right to conduct such activity.

Delhi rightly rejected the allegations, it also pointed to two important aspects which got smothered by the noise generated by the media. The first was that it was unbecoming of the West to reveal confidential information against the basic principles of international intelligence cooperation. The second aspect relates to a certain indignation that New Delhi could attempt to conduct such activity on their own soil.

The Canadian media reports were followed by US media houses going gung-ho about how Modi’s India targeting dissidents seeking protection overseas ‘as part of a wave of aggression’. The Washington Post (April 29, 2024) claimed that former R&AW chief Samant Goel had ordered the alleged plot to kill Khalistani sympathizer and supporter, Gurpatwant Singh Pannun on US soil. Strangely, nowhere does this narrative mention that Pannun is a terrorist wanted in India for promoting the Khalistani cause. The Post story links the killing of Nijjar with the Pannun plot to the targeted killings of terrorist entities in Pakistan, alleging that R&AW is behind the act.

Furthermore, the Canadian actions of making selective leaks to the media provided India’s western neighbor, Pakistan with an excuse to allege that India was involved in the killing of individuals and entities closely linked to terrorist infrastructure inside Pakistan. At last count, more than 25 jihadi elements have been killed inside Pakistan since 2020, the latest instance being the killing of Hafez Saeed’s close aide, Abu Qatal, on 16 March 2025. Qatal, an Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT) operative and nephew of Saeed had been charged by India for the 2023 Rajouri attack and 2024 Reasi attack, was killed by unknown assailants in Peshawar. The UK Guardian newspaper claimed (April 04, 2024) these killings were ‘orchestrated’ by sleeper-cells put in place by R&AW operating out of the United Arab Emirates.

Soon after the Nijjar killing in Canada, the Guardian reported that a secret ISI document had revealed India’s plans to target and kill all terrorist entities based in Pakistan who were responsible for attacks in India or on Indian interests. The newspaper cited an unnamed Indian intelligence official who reportedly stated that R&AW wanted to pre-empt the terrorists and therefore, ‘with clearance from the highest level in the government’ decided to strike at terrorists inside Pakistan and elsewhere. The underlying message became clear that India was now on the warpath and would do anything, even if it meant operating in enemy territory to eliminate its opponents, especially those linked to terrorist networks. Thus, be it pro-Khalistani elements in Canada or terrorist entities in Pakistan, the Indian state was willing to strike to the heart of the enemy, a determined India.

The trail of killings across Pakistan uses similar tactics and targets are usually high-profile entities associated with leading terrorist organizations like the Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Tayyaba. Recall that in December 2024, Abdul Rehman Makki, the second-in-command of the LeT and a mastermind of the 26/11 Mumbai attacks, was killed. Hafiz Saeed has since been in mortal fear of being targeted and even refrained from attending Makki’s funeral. However, more importantly, most of those killed are those wanted in connection with attacks in India like 26/11. This generates a motive for India’s involvement. It is probable that the Pulwama attacks in 2019 triggered Indian thinking on the issue. Past experience shows that India had the capability, the challenge was the overseas dimension. But it would have been easy to hire someone to do the job, rather than get directly involved.

The covert dimension to intelligence operations globally is well known and instances of such activity abound during the cold war. This was mainly a consequence of the rivalry between the US and Soviet Union. Today, the same rivalry has brought China into the frame. A 2022 New York Times report (September 14, 2022) informed that China’s economic and military influence had enabled ‘covert operations that extend well beyond the traditional intelligence gathering’ and that these had grown in scale and threatened to ‘overwhelm’ Western security agencies.

Similarly, Israel has for long used covert action to meet its national security interests. Targeted killings of Hamas and Hezbollah leaders and cadres in recent years reflect their ever-increasing sophistication. In all cases, the factor of deniability is very important. India is not far behind when it comes to covert action and many instances have contributed to the national interest. R&AW’s role in the creation of Bangladesh is a case in point.

As questions swirl over India’s alleged role in overseas assassinations, particularly in Pakistan and Canada, it is worth noting that such operations are not without precedent in Indian intelligence history. In the realm of counter-terrorist operations with regards to Pakistan, former R&AW officer B. Raman first revealed (The Kaoboys of R&AW) the operationalization of CIT-X and CIT-J units by R&AW in the 1980s to tackle Pakistani terrorists and Khalistani extremists. The former unit was tasked with targeting terrorist elements within Pakistan, while the latter focused on getting rid of Khalistani extremists, both within India and in Pakistan. These disclosures offer a historical lens through which to view current developments — including a spate of targeted killings in Pakistan involving individuals affiliated with designated terrorist groups. While no official confirmation has emerged, the precision and pattern of these attacks have inevitably raised questions about whether Indian intelligence is once again operating across borders with deliberate intent.

That such speculation now arises so readily speaks to both the increasing sophistication of India’s intelligence apparatus and the evolving nature of its national security doctrine. But interpreting these developments requires a calibrated perspective — one that balances the imperatives of state security with the norms of international conduct.

The real question may not be whether such operations occurred, but whether India, like other global powers before it, now sees covert action as a necessary, if controversial, tool of statecraft.

Covert action acts as a deterrent and supplements foreign policy. However, in some cases, like that of what is occurring in Pakistan, the deterrent factor is very much at play. After the surgical strikes in 2016 and Balakot aerial strike, it became necessary to target Pakistani operatives (as well their proxies including the Khalistanis) on foreign soil. The scale and intensity of this Indian operation will be debated for a long time, but the results as far as Pakistan is concerned are there for all to see. Further, embroiled in Afghanistan and the economic downturn domestically has ensured that Islamabad’s focus remains internal.

Accusations of targeted assassinations by India in the Western media are not new. The pitch made today is more by way of questioning India’s need to engage in such activity. Perhaps a gentle reminder is needed for those who don’t play by the rulebook that others too can play the same game, in their national interest. Covert action by India that is both deniable and effective must be engaged in. This approach must dovetail with diplomatic action whenever and wherever required. What is required is a recognition of India’s skills in this regard, but ‘leaking’ of the use of such capability is best avoided. That is the message that New Delhi has consistently conveyed to its friends around the world.