The regulations which the government notified in June vest the central government with the power to approve the diversion of forest land for industrial and infrastructural purposes without the consent of forest-dweller gram sabhas, greatly abridging the rights they are entitled to under a landmark Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006.

Now, the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Rules, 2022 allow the Centre to give final approval for the use of forest land for non-forest purposes. But before land acquisition happens, state governments have to settle rights of project-affected persons under the 2006 law, popularly known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA). Under the FRA, forest-dwellers could not be evicted till their rights are recognised (or their claims rejected). This means rights holders will be entitled to compensation and rehabilitation for loss of land, livelihoods, and habitats but cannot veto their displacement.

This is not a harmonious reading of the Forest Conservation Act with the Forest Rights Act, which recognises 13 individual and community rights of forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest-dwellers (OTFD). These include the right to use the land they occupy for housing and cultivation and to convert pattas, leases, and grants given by local authorities into titles. Communities have grazing and fishing rights and are entitled to collect, use, and sell minor forest produce like bamboo, cane, tussar, honey, wax, lac, tendu leaves, and medicinal herbs. Other traditional rights are recognised but not the right to hunt or trap wild animals.

The Forest Rights Act, 2006

The FRA recognises the rights of those Scheduled Tribes who were ‘primarily resident’ on forest land in their possession as of December 13, 2005. This condition also applies to Other Traditional Forest Dwellers, except that they should also show that they were in possession of the land for three generations as of that date, each generation being counted as 25 years. That is, they should have inherited land occupied on or before December 13, 1930.

The process of recognition and vesting of rights under the FRA requires the gram sabha to call for claims, which should be filed within three months. They will consolidate the claims, verify them, prepare a map delineating each claim and pass a resolution recognising and vesting the right with the district collector’s endorsement. For the resolution to be valid, at least 50% of the gram sabha members have to be present, and at least half of those present must be rights holders or claimants.

The Act allows forest land to be used for amenities like schools, dispensaries, water tanks, anganwadis, fair price shops, roads, electricity and telecommunication lines and minor irrigation canals provided the area used is less than one hectare and has the gram sabha’s assent. Under the Act, no forest dweller can be evicted unless their rights are recognised.

Vinod Tiwari, an Indian Forest Service officer and additional secretary, Ministry of Coal, differs. He says gram sabha consent is not needed under the FRA for diversion of forest land for non-forest uses like industrial and infrastructure projects. He says the Act is for the recognition of rights of forest-dwellers. When displaced from their lands, the rights holders are entitled to compensation, rehabilitation, and resettlement under a 2013 law.

Tribal rights activists see this as a narrow reading of the FRA. They agree that gram sabha consent is not expressly mandated in the Act. But it is implied by the right given to communities “to protect, regenerate or conserve or manage any community forest resource, which they have been traditionally protecting and conserving for sustainable use”. How can they exercise this right when displaced from their habitats, they ask. This is also the view of the tribal affairs ministry. The FAQs or explanations of FRA provisions on its website state this.

The amendments to the Forest Conservation Rules, carried out earlier this year, go against principles which the Supreme Court enunciated in a 2013 ruling while upholding the environment ministry’s rejection of approval given to the Orissa Mining Corporation for extracting bauxite in Niyamgiri for Vedanta’s alumina refinery. Mining would have impacted the livelihoods and way of living of Dongaria Kondh and Kuthia Kondh tribals, the court noted. The hill abode of their deity, Niyam Raja, would suffer collateral damage. The Supreme Court said gram sabha consent was needed for diversion of forest land under the FRA and they should factor in not only economic rights but also cultural and religious ones in their decisions.

The new rules supersede the ones notified in 2017. Those required the district collector to not only complete the process of recognising and vesting of rights under the FRA but also “to obtain consent of each gram sabha having jurisdiction over the whole or a part of the forest land” indicated for diversion. The July and August 2009 guidelines of the environment ministry imposed similar conditions. Each proposal for diversion of forest land had to be accompanied by letters “from each of the concerned gram sabhas” saying that the formalities and processes under the FRA for settlement of rights had been carried out and their informed consent had been obtained.

Tribal rights activists see this as a narrow reading of the FRA. They agree that gram sabha consent is not expressly mandated. But it is implied by the right given to communities to protect or manage community forest resource

“It is completely wrong,” says Raipur-based Alok Shukla, convener of the Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan (CBO), when asked about the amendment. CBO is a platform of 23 tribal rights groups which has been protesting against the opening of the Hasdeo Aranya coal belt for mining. (See box.) Shukla says the amended forest conservation rules would put the state government in conflict with tribals because they would have to deal with the fallout of the Centre’s approvals.

Hasdeo Aranya Coal Belt

This is a 45,883-hectare area with 23 coal blocks. In 2010, Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh designated it as ‘no-go’ for mining. No-go means no forest clearance. A coal block having 30% or more area under forest cover was ‘no-go’. Weights were also assigned to forest quality. Very dense forests had a weight of 0.85, moderately dense forests 0.55 and open forests 0.25. An area with weighted forest cover of 10% was ‘no-go’.

Currently, seven blocks have been allocated to different companies. In 2011, Ramesh reversed his decision and allowed mining in one block, citing six reasons. This block was allotted to Rajasthan’s state power production utility. The mining was done by an Adani company. Mining operations in Parsa East Kete Basan (PEKB) Phase I began in 2013. In 2014, the National Green Tribunal stayed mining on the grounds that the environment ministry had not considered the impact on biodiversity, including on elephants. The Supreme Court stayed the order. But the mine has been exhausted and it is closed.

When PEKB Phase II was being prepared for mining with the felling of trees in February, tribals erupted in protests that are continuing. The state government withdrew clearance to two blocks allocated to the Andhra Pradesh Mineral Development Corporation and Chhattisgarh’s state power generation utility following gram sabha protests. The Centre has taken four blocks off the auction list at the state government’s instance. In August, an MLA from former Chief Minister Ajit Jogi’s Janata Congress Chhattisgarh introduced a resolution in the assembly urging the government to withdraw clearances for all allotted blocks where mining has not commenced.

Tiwari says activists ensured the rights were vested in forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes in campaign mode after the FRA came into effect in January 2008. The pushback, in his view, is mainly from those OTFDs who have difficulty in proving occupation since 1930. They do not let gram sabhas convene, knowing they cannot be evicted so long as their claims for rights are not recognised or rejected.

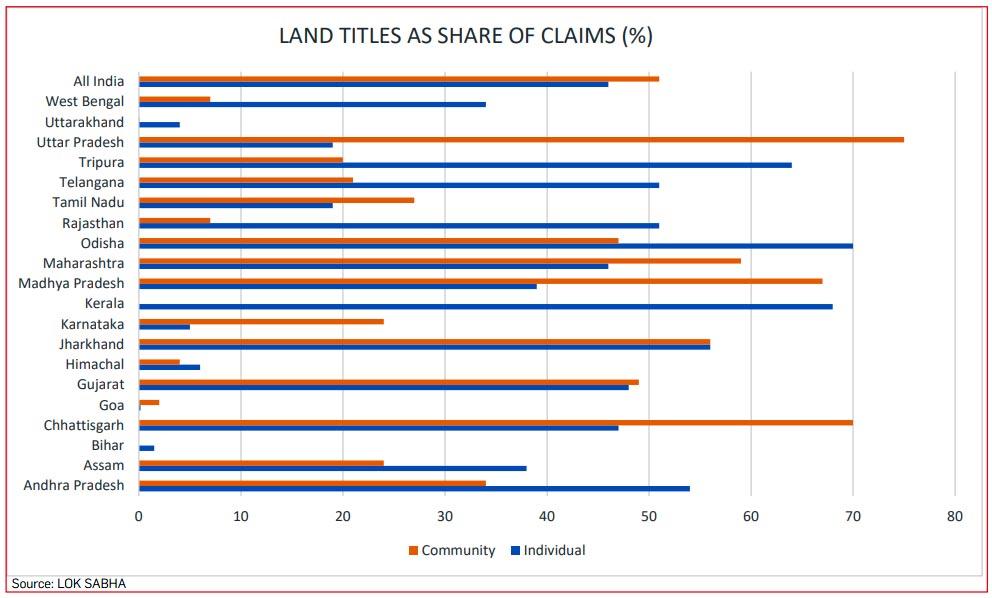

STs and OTFDs have filed a large number of claims for recognition of their rights. Up-to-date figures are not available, but in reply to a question in the Lok Sabha the government said that 4.09 million individual and 1.49 lakh community claims had been filed as of September 30, 2020. But the rejection rate is quite high. At the national level, 56% of individual claimants and 49% of community applicants did not get titles. (See graph for state-wise details.)

Congress Party Opposes The Latest Amendments

The Congress party says these amended rules will end the ‘ease of living’ for the vast many. The amendments destroy the purpose of the FRA, it says. Once forest clearance is granted, everything else becomes a mere formality and almost inevitably no claim will be recognised or settled. The state governments, it says, will be under even greater pressure from the Centre to accelerate the process of diversion of forest land. The new rules have been promulgated without consultation of even the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Environment, Forests and Climate Change. The Forest Rights Act, 2006 wanted the Forest Conservation Act, 1960 to be implemented in a manner that is consistent with it

Even in areas where gram sabha or panchayat approval is mandatory for land acquisition, state governments carve out exemptions, says Ulka Mahajan, founder of the Raigarh (Maharashtra)-based Sarvahara Jan Andolan (SJA). The Provisions of the Panchayat (Extension of the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) apply to Fifth Schedule areas. These are tribal majority areas in 10 tribal minority states (excluding the Northeastern states). Tribal land in Palghar and Thane districts was acquired through such carve-outs, says Mahajan. The SJA was active in opposing Mukesh Ambani’s 14,000-hectare Navi Mumbai Special Economic Zone.

According to Shukla, in Chhattisgarh, coal mine developers and the state government have tried to bypass PESA, saying it is not applicable to land acquired for coal blocks under laws that pre-date it, like the Coal Bearing Act, 1957. Gram sabhas were sidelined on this pretext in the Parsa coal block allocation, Shukla says.

Though compensation for acquired forest land is four times the price fixed by the government for purposes of stamp duty (the ready reckoner rate), or the average of registered property prices in the past three years, the amount which land losers get can be quite low. Mahajan says forest dwellers who lost land to Chippi airport in Sindhudurg district of Maharashtra got “a few thousand rupees” that would not last even a few months. The Chhattisgarh government has set floor rates, according to which forest land losers will get four times the average of three years’ market prices or at least ₹6 lakh an acre for non-agricultural land, ₹8 lakh per acre for agricultural land and ₹10 lakh per acre for double cropped land. But people dependent on forest resources cannot be adequately compensated in cash. The loss extends beyond the current generation, says Mahajan.

It is clear that the forest conservation rules have been amended to ease the business of mining. Despite the emphasis on renewables, coal will remain the mainstay of India’s energy production. Eighty percent of power is now produced from coal. The demand in 2021-22 was 914 million tonnes, of which 741 million tonnes was domestic supply. According to credit rating agency CRISIL, power demand grew by 6% in 2021-22, for the second year in a row, above the pre-pandemic long-period average of 5%. The government wants coal production to grow by 7% to 8% a year to meet rising power demand and reduce dependence on imported coal. Demand for coal is expected to peak at 1.5 billion tonnes in 2030. That would require extensive mining and expeditious diversion of forest land.

The government said that 4.09 million individual and 1.49 lakh community claims had been filed as of September 30, 2020. But government data shows the national rejection rate is high

Project developers, according to Tiwari, are willing to pay the cost of diversion of forest land, including compensation to rights holders, rehabilitation, and compensatory afforestation. It is the delay in handing over land that affects project execution with a ripple effect on the national economy.

Whether it is the Char Dham highway connecting Kedarnath, Badrinath, Yamunotri and Gangotri in the Himalaya, the inter-linking of rivers or mining in forested areas, the Modi government has been impatient with environmental concerns. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been vocal about the judiciary holding up clearances. In February, the Indian Express reported that veteran environmentalist Ravi Chopra had resigned as chair of the high-powered committee (HPC) set up by the Supreme Court to oversee the Char Dham highway, saying his “belief that the HPC could protect the fragile (Himalayan) ecology has been shattered,” after the court allowed wider roads than the HPC had recommended, for strategic reasons.

Tiwari says Nimby (not in my backyard) makes little difference to global warming. If coal is not produced domestically, it will have to be imported. Reduced consumption and frugal living—which people are not willing to accept—will reduce overall planetary emissions, not sourcing coal from Australia or Indonesia. To mitigate the environmental fallout of mining, he proposes mixed-tree species forestry on agricultural land that is fallow for reasons like a shortage of farmhands due to people migrating to cities for better paying occupations, or farm owners not being able to manage crop agriculture for whatever reason.

Currently, compensatory afforestation begins after a project is awarded. Between the felling of forest trees for mining projects and the development of compensatory forests there is a net addition of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. This gap can be closed if farmers grow forests on fallow land which they could sell or rent out to mining projects towards meeting their forestry obligations.

Our forests don’t just provide ecological services. They sustain the lives of 275 million rural people, according to a 2005 World Bank report. Mining imposes costs on them

But can a plantation replace a natural forest that has evolved over centuries? Restoring a limestone or dolomite quarry or an open cast coal mine is not easy because the topsoil is buried under excavated overburden, which is dead soil. But it can be done as Delhi University’s Centre for Environmental Management of Degraded Ecosystems (CEMDE) demonstrated at Purnapani, near Rourkela. (See box.)

Restoring A Dolomite Quarry

Purnapani is about 40 km from Rourkela. It was a dolomite (iron ore) and limestone quarry of the Steel Authority of India. Work on ecologically restoring the 200-acre area began in 2007. This is a tough job because in mines and quarries the topsoil is buried under overburden, which is dead soil. Ecologically restoring an abandoned quarry or mine begins with planting of grasses and legumes to attract soil microorganisms. These microbes enhance the soil’s organic carbon content and its moisture retention capacity.

C.R. Babu, professor emeritus of Delhi University’s Centre for Environmental Management of Degraded Ecosystems (CEMDE), says Purnapani is now a five-storeyed forest of native species, with the tallest trees about 100 feet high. The number of species has reached 250 against 50 to 60 species usually found in forests. To give tribals a stake in sustaining the forests, there are enclaves of ber, arjuna and asan trees which host tussar silkworms. There are also patches with trees and plants that attract lac insects and honeybees. The quarry is now a reservoir teeming with fish.

The initial cost of restoration was estimated at ₹3 crore. Babu says in all about ₹8 lakh per acre—or about ₹16 crore—has been spent. Restoration is inexpensive, he says, but takes time, effort and dedication. CEMDE is also developing biodiversity parks at the Bhurkunda and Damoda coal mines in Jharkhand.

Babu says Purnapani should be the model for compensatory afforestation and there should be a national mission to restore exhausted mines.

Our forests don’t just provide ecological services. They sustain the lives of 275 million rural people, according to a 2005 World Bank report. Mining imposes costs on them while the gains accrue disproportionately to another set of people. Even if it pinches, it might be better to import costlier—and better quality—coal from liberal democracies like Australia with governance structures that minimise social and ecological costs, than displace vulnerable people living in sensitive ecologies in our country, where corporates have little regard for regulations. The amendments to the Forest Conservation Act should trigger a debate on the trade-off between economic growth and its environmental sustainability. The economy-wide costs of extreme weather events caused by destroyed forests might be more than the economic gains of cheaper power.