This they do by cutting down this invasive species, South American Mesquite, turning it into biochar and applying it to their fields to improve soil quality and secure a sustainable future for their land and livestock.

Hitherto they had been producing charcoal from mesquite wood (botanical name Prosopis Juliflora).

Charcoal had a market in nearby industries that wanted to meet their energy demands through recycled carbon rather than fossil fuel. But today, instead of charcoal the herders produce biochar which is mixed with compost and ploughed back into the field and no longer burnt. This process ensures that the carbon that would otherwise have been released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide is trapped in the soil earning them carbon credits for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and carbon sequestering. The credits are then monetised in the international carbon market.

In 2022-23, pastoralists from Bhuj, major contributors to milk to cooperatives like Amul, generated 2000 carbon credits valued at $183,000 (Rs. Twenty crore approximately). They produced 800 tonnes of biochar and in the bargain were able to benefit the ecosystem of the region by improving soil quality that helped restore 11 square kilometres of grasslands.

While the beneficial effects of charcoal (of which biochar is a form) on soil fertility is believed to have long been known in practices of slash and burn agriculture in many parts of the world including India (Jhoom) for at least 2000 years. Its use as a means of carbon capture has only begun to receive attention of environmentalists in recent years. Initially the interest was confined to the use of biochar for soil improvement. Its potential as a mechanism of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and carbon sequestration began to gain serious attention only in the wake of the 2015 Paris Climate Summit, that underlined the threat posed by global warming and pushed for urgent steps, not just to cut current emissions but towards reducing the total amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

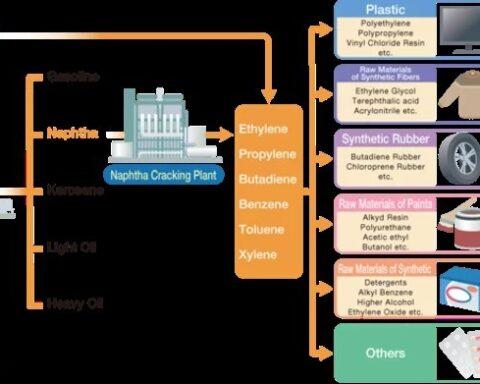

BIOCHAR: AN ALTERNATE FUEL

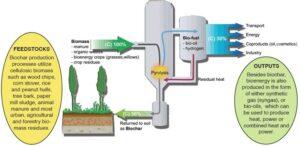

Both biochar and charcoal are carbon-rich materials obtained by burning biomass in limited oxygen at about 400⁰ to 600⁰ C in a controlled process called pyrolysis. The main difference is in their end use – charcoal is mainly used as a fuel while biochar is used both for soil enhancement and carbon sequestration. In modern pyrolysis methods biomass is burned in a container with little oxygen. As the materials burn, the flame ‘curtain’ produced by the fuel gases allows little to no contaminating fumes to escape. An added advantage: the bio-oil or syngas, a fossil-fuel thus produced during the process can be used for low grade heating or, even as bio-diesel after suitable treatment.

The production of biochar presents a viable alternative to the common post-harvest practices on farms, where biomass is either left to decompose or, when time is short before sowing, burned. Both methods release harmful green-house gasses (GHG) into the atmosphere. Decomposition results in the release of methane and burning produces carbon dioxide, both GHGs deplete soil nutrients. More troubling still, burning rice and wheat stalks releases toxic gases and large amounts of particulate matter, posing serious health risks to millions of people.

The production of biochar presents a viable alternative to the common post-harvest practices on farms, where biomass is either left to decompose or, when time is short before sowing, burned. Both methods release harmful green-house gasses (GHG) into the atmosphere. Decomposition results in the release of methane and burning produces carbon dioxide, both GHGs deplete soil nutrients. More troubling still, burning rice and wheat stalks releases toxic gases and large amounts of particulate matter, posing serious health risks to millions of people.

Instead of burning or leaving crop residue to decompose, converting it into biochar — a solid mass composed of 70 to 80 percent carbon — offers a far more beneficial alternative. When this biochar is powdered and mixed with compost in the soil, it enhances soil quality in numerous ways, including significantly boosting its water retention capacity. But it provides a much more crucial service to check global warming by sequestering carbon as the biochar (carbon) remains locked in soil for hundreds of years.

Crops capture climate-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere for their growth through photosynthesis, while when their residue is converted into biochar, the captured carbon can be stored in the soil. This meets all the requirements for being added to the carbon sink which records carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, converted into storable form, and verifiably stored outside the atmosphere. Every carbon unit, equivalent to one tonne of carbon dioxide, sequestered through biochar methods is certified only after the carbon trail is meticulously and transparently followed from its extraction from the atmosphere to its final storage point. In carbon markets the unit is also known as a tradeable carbon credit.

Crops capture climate-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere for their growth through photosynthesis, while when their residue is converted into biochar, the captured carbon can be stored in the soil. This meets all the requirements for being added to the carbon sink which records carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, converted into storable form, and verifiably stored outside the atmosphere. Every carbon unit, equivalent to one tonne of carbon dioxide, sequestered through biochar methods is certified only after the carbon trail is meticulously and transparently followed from its extraction from the atmosphere to its final storage point. In carbon markets the unit is also known as a tradeable carbon credit.

BIOCHAR PRODUCED GLOBALLY

In 2020, Biochar was accepted as a scientifically grounded climate protection strategy formally for the first time in Europe. Where, carbon sinks created by industrial production of biochar and its subsequent application in agriculture began to be certified initially in accordance with European Biochar C-Sink (EBC) standards and later in accordance with Global Biochar C-Sink standards to create tradeable climate services.

In 2020, Biochar was accepted as a scientifically grounded climate protection strategy formally for the first time in Europe. Where, carbon sinks created by industrial production of biochar and its subsequent application in agriculture began to be certified initially in accordance with European Biochar C-Sink (EBC) standards and later in accordance with Global Biochar C-Sink standards to create tradeable climate services.

The window of opportunity for small farmers of developing countries like India opened in 2022 when the Switzerland-based Ithaka Institute began to develop a mechanism of monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) of small-scale production of biochar. Small farmers producing limited quantities of biochar from their field waste were designated as artisan producers. In March 2024 Global Biochar C-Sink Register issued a set of guidelines for carbon sink certification for artisan biochar production, which could be registered on the newly-created Global Artisan C-Sink. The guidelines created the basis of a trustworthy artisan carbon sink designed to accommodate small-holder farms as well as farmers cooperatives. These guidelines were made applicable only to low income, lower middle-income and higher middle-income countries.

India is one of the world’s largest producers of cereals, generating an estimated 228 million tonnes of surplus crop residue annually, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE). However, much of this residue comes from small farms, typically ranging from 1 to 2 hectares, where the volume produced is uneconomical to justify the operation of industrial-scale biochar production plants. But new guidelines could pave the way for India to generate enough carbon credits to either meet its net-zero emissions targets or trade them on global carbon markets.

India is one of the world’s largest producers of cereals, generating an estimated 228 million tonnes of surplus crop residue annually, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE). However, much of this residue comes from small farms, typically ranging from 1 to 2 hectares, where the volume produced is uneconomical to justify the operation of industrial-scale biochar production plants. But new guidelines could pave the way for India to generate enough carbon credits to either meet its net-zero emissions targets or trade them on global carbon markets.

PASTORAL PRODUCERS:

The practicality of this approach was demonstrated by the semi-nomadic herders of Kachchh, whose raw material was not crop residue but the invasive Mexican Mesquite, which is converted to biochar in Kon Tiki kilns operated by the farmers.

The biochar is then applied to the soil, improving water-retention capacity among other benefits. Gurugram-based climate-tech company Varaha Earth assists the herders in recording data on the amounts of biochar produced, the source of their feedstock, and the application of the biochar to the land. The company also helps convert this data into carbon credits, which are then sold on international voluntary carbon markets. The partnership was facilitated by Bhuj-based non-profit Sahjeevan which acted as the bridge with Varaha on behalf of the herder communities. “It’s a win-win situation,” said Sandeep Virmani, founder president of Sahjeevan who has been working in the region for three decades.

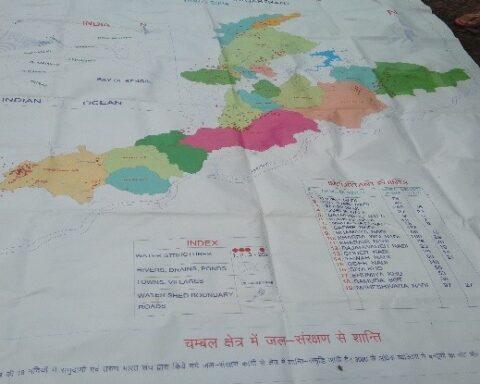

Sahjeevan has played a key role in organizing the Maldhari pastoral community of Kachchh, whose cattle graze on the Banni Grasslands — the second largest in Asia. These grasslands, however, are under threat from the invasive mesquite tree. It was introduced in the area over half-a-century ago, at a time when the dominant view about the environment considered Kachchh as a marshy desert wasteland which needed to be drained out and re-greened. It wasn’t until a few decades later that the true value of the 2,500 square-kilometer grassland was recognized, as it became clear that the diverse ecosystem it supported was rapidly disappearing, with mesquite now spreading across 1,500 square-kilometer.

While efforts to root out mesquite has been underway since 2012, it began to make a headway only after 2019 when Sahjeevan succeeded in assisting village panchayats in the region to form community forest resource management committees (CFRMC) under the 2006 Forest Rights Act. These committees supervised the burning of mesquite wood in small scale Kon Tiki kilns to convert it into biochar, powder it and apply it to the grasslands, thus meeting the criteria for certification by Global Artisan Biochar.

The challenge, however, lies in the fact that instead of a single centralized plant, there are hundreds of small-scale kilns. Pastoralists must be trained not only to operate these kilns properly but also to track and register the quantities of biochar produced, as well as the source of the feedstock, in order to secure certification. This is where Varaha Earth comes in, offering the technical expertise needed to aggregate biochar production from these small-scale producers. The company ensures that the herders adhere to carbon-neutral, nature-based practices, streamlining the process and making certification possible.

Kaushal Bisht, marketing head of Varaha, in an interview with Tatsat Chronicle, said that the herders who were producing biochar and following green practices registered themselves on an application developed by Varaha. “Datasets were collected that obtained insights into whether that land and green practices were in place,” he added. Validation is done through satellite imagery of the key characteristics of farms and forests and identified through remote sensing models using observations from satellite imagery, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and widefield plot network. Varaha has an interface with the Global Artisan Biochar registry where it registers the carbon credits of the Kachchh herders.

“High quality carbon credit generation through removed or sequestered GHGs are further converted into high quality carbon credits via third party validation, verification and issuance through Verra and other credible agencies,” said Mr. Bisht. The credits are then purchased by institutional buyers interested in offsetting their GHG emissions.

Writer: By Kalyan Chatterjee