The recent adoption of the United Nations High Seas Treaty, also known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty, appears to have driven another nail in the coffin of the freedom of the seas principle that originated in the colonial era. The creation of a regime to conserve marine biodiversity in the oceans of the world underlines that the high seas are a common heritage for the benefit of mankind and cannot be cornered by a few powerful industrialised nations to profit from exclusive mining rights in the name of freedom of the seas.

The move to curtail the freedom to exploit the resources of the seas was first made more than half-a-century ago, ending with the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982. It has been reinforced by the BBNJ Treaty, expected to come into force in January 2024, having obtained the approval of 84 countries — well above the minimum requirement of 60. Like UNCLOS, the new treaty also extends to about two-thirds of all the world’s oceans lying beyond the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Finalised in June 2023 after scores of meetings and negotiations spread over nearly a decade, the BBNJ Treaty was opened for signature during the General Assembly session this September.

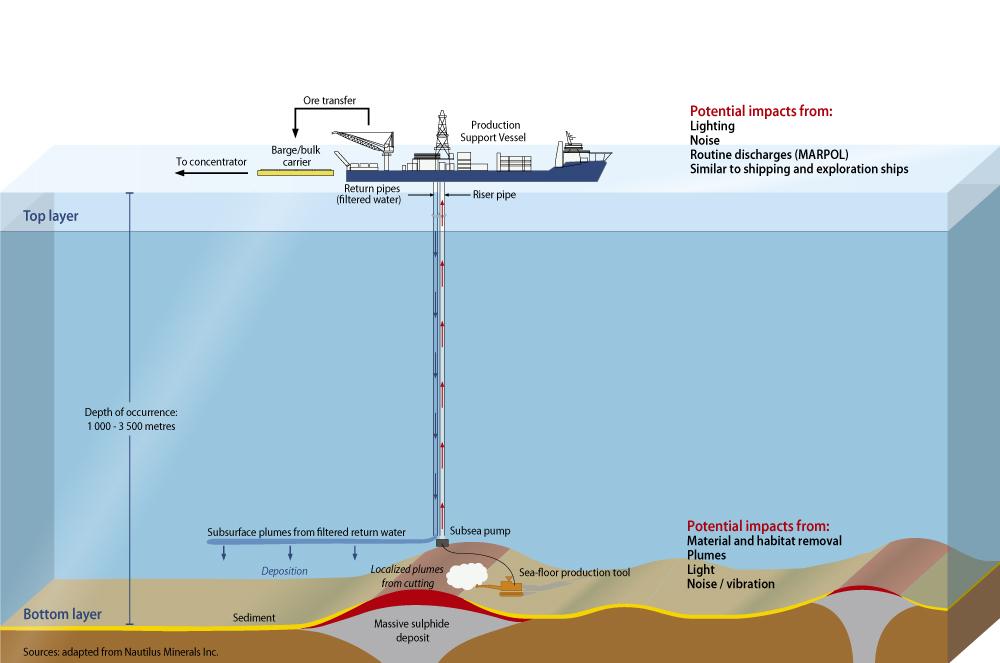

To conserve biodiversity of the high seas, the Treaty sets up a regulatory framework not only for equitable use of marine genetic resources (MGR) but also for setting up marine protected areas (MPA), especially in Arctic and Antarctic areas. Activities involving mining and research in the MPAs must not only be sustainable but be consistent with the objective of conservation. This, naturally, will affect activities on the seafloor to collect mineral nodules. India, incidentally, has not yet signed the Treaty.