But where moral persuasion and peaceful efforts by Sarvodaya leaders like Vinoba Bhave and Jaya Prakash Narayan achieved limited success, the rejuvenation of rivers in Karauli district of Rajasthan on Chambal Basin seems to have done the trick. As water began to flow in the rejuvenated rivers, round-the-year groundwater and wells were recharged bringing greenery and agricultural prosperity to this arid and impoverished area. This in turn persuaded the bandits to give up their life of crime and work for water conservation and farming instead – a true change of heart.

The Diagnosis No One Expected

The real issue, however, was identified in 1986, by Mangoo Kaka, an elderly villager from Gopalpura village, in Alwar district (not Chambal basin). Mangoo put his finger on the heart of the problem – the severe shortage of water, made farming impossible and forced the village youth to migrate to nearby towns for a livelihood. Night blindness was common in the area and Mangoo too had been a victim, till he was cured by Dr. Rajendra Singh of Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS), who worked on government-sponsored health and educational projects in the area, in 1986. He told social worker Dr. Rajendra Singh something no official report had captured: “Treat the earth. Put water back into its belly.”

This could be accomplished by using traditional ways of conserving rainwater. For generations, traditional water-harvesting structures had sustained these semi-arid landscapes. In the past it was practiced, before the government introduced programmes of groundwater development – borewells, mining, etc. However, boring had an adverse impact – a steady decline in the water table was observed, so much so that, parts of Alwar had to be declared as a dark zone –no surface water, no subsurface water and no ground water. Borewells, mining, and deforestation had drained the land dry, driving young men toward migration—and in the Chambal region, toward crime.

Mangoo himself though old and frail, offered the traditional know-how; Dr. Singh and the Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS) team provided the muscle. Together they rebuilt Johads and check dams, slowing monsoon runoff and reviving aquifers. Over time, this process recharged groundwater and within a few years brought flowing rivers perennially. Rainwater from the hill tops of the Aravalli Range in Alwar, that earlier used to rapidly runoff the slopes, now collected in the waterholes and recharged groundwater, through aquifers of horizontal fractures in the red sandstone rocks, not only at the lower levels but also the rivers. Villages that had been written off as “dark zones” saw wells refill, fields bloom, and rivers flow again.

Water as a Weapon for Peace

The ripple effects of severe water shortage crossed into the notorious Chambal Basin. Dr. Singh’s attention was drawn to the Chambal area by a lady named Bhagwati Gurjar from Alwar. Bhagwati was married off for money to a dacoit Jagdish, in Karauli, Chambal region, who abandoned her soon after their wedding. The breakthrough came when Bhagwati returned to her home in Alwar years later, and saw the transformation water had brought. She urged Dr. Singh to help her at the drought-stricken Karauli village Chaudakiya Kalan, which suffered from a similar scarcity of water.

A small dam on her land changed everything!

Bhagwati harvested her first bumper mustard crop and invited Jagdish home with new clothes bought from her earnings. The hardened bandit, Jagdish was moved by these emotions, in a way sermons never achieved. Soon Jagdish surrendered, served his sentence, and joined TBS’s water work. Not only this but Jagdish also persuaded many other bandits to give up their violent ways and work to conserve water that could provide them with gainful employment, food and freedom from fear of the police, now that water was available.

The transformation in Gopalpura was magical. Water levels rose in 20 nearby wells and agriculture was resumed in 100 acres of farmland. Further, grass began to grow around the pond and trees started to flourish and the ecosystem restored. Dr. Singh eventually went on to win the Magsaysay Award in 2001 for the work on water conservation, but more significantly he was able to spread the experiment to the neighbouring Chambal Basin Districts as well.

Lives Rewritten by Water

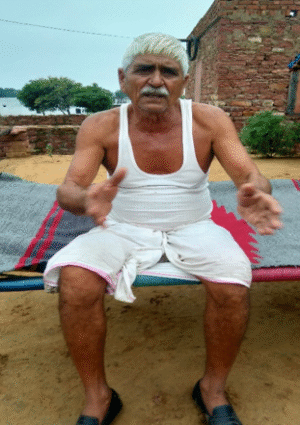

Former bandit Bachhi Singh((68) of Bhudkheda village in the former princely state of Karauli in Eastern Rajasthan, 280 km south of Delhi, is a perfect example. Less than 30 km to the east lie the Chambal River and its notorious ravines whose maze-like twists and turns provided a safe-haven to dacoit gangs of yore. Especially as police were afraid of entering the area. As of 2023, more than 1500 people have quit crime and violence and are now engaged in water conservation activities and farming, according to TBS.

Bachhi is one of more than 1,500 outlaws who have left crime since water revived the Sherni River and its tributaries. Today he sits peacefully on a charpoy, sharing a hookah with his brothers, far from the days of hiding in the ravines. He no longer suffers from the anxieties from constantly running from the police. Like many others Bachhi had several serious cases registered against him. “Now I am free from all cases”, he says. From the raised red-sandstone-and-mud platform next to a lean-to can be seen a row of five pucca (brick-and-mortar) houses in the distance that belong to Bachhi and his four brothers. “I am contented,” he says. “I no longer frighten anyone, nor am I afraid of anyone. Everyone has started loving me and my family is happy.”

Why shouldn’t he be? Thanks to water availability round the year, enough wheat, millets and maize and fodder now grow on their land to feed their families and cattle. Some surplus is left for the market as well. “Production of wheat and maize has increased ten-fold,” said Dr. Rajendra Singh whose TBS pioneered the rejuvenation of rivers in the region. Water chestnut cultivation and pisciculture are the spinoffs that have supplemented their incomes further. The return of water restored not just fields but dignity.

From Badlands to Farmlands

But it wasn’t always this way. Till barely a few years back, Sherni River, a tributary of the Chambal, saw water flow only during the monsoon months. For most parts of the year the river was bone dry. By 2010, wells and borewells dried up, due to over-drawing of groundwater and no recharge. Further, monsoon water just rushed down the slopes as traditional conservation structures fell into disrepair. The culprits were deforestation and sandstone mining. Groundwater was tapped for use in stone cutting and washing the red dust, which then flowed into fields making them barren.

It must be pointed out here that the average annual rainfall in this district is between 20 and 25 inches.

TBS began working in the village of Bhood Kheda only about a decade back, though work in Karauli started 35 years back.

The first step was building of a 100-metre-long stone. Followed by an earthen dam next to a depression on the hills slope’s first level, creating a waterhole known as Kaachre Ka Tal. It filled up during the monsoons and stopped the water from running off the slopes. Only after it was full, the water overflowed from a spillway into the narrow sub-stream of the Sherni, that originates in the forests of Banswari.

The Sherni used to be perineal till about 1980, after which the river was flowing only during the monsoon. But once Kaachre Ka Tal filled up with water, it not only flowed into the sub-stream through the spillway, but an additional trickle flowed into it from the horizonal fracture in the surrounding rocks, and groundwater recharged.

Water from the waterhole was used to irrigate surrounding fields at a lower level through siphon action – no polluting motorised pumps. Anicuts were constructed further downstream, as the stream got wider. In a Kunda village, a well that had run dry a few years back, was filled with water, while water gushed out of a borewell next to the main stream, which too had run dry previously.

Soon, all around were farmlands in which paddy has been sown, as jowar (sorghum) crops ripen. Overall, the picture in this rural village of Karauli is one of prosperity which returned with the rejuvenation of rivers. Water was now available for not only irrigating fields but also providing sufficient water and fodder for cattle.

A Lesson for a Heating Planet

Rainwater conservation in Karauli village, not only led to rejuvenation of rivers, also in turn led to rejuvenation of ecology and livelihood in the short run, and mitigation and resilience in the long run. Most importantly, it had a positive social impact in weaning dacoits away from a violent life of looting and extortion.

According to a document, ‘Rejuvenation of Rivers’, October 2022, increased droughts and floods are the result of a development model, that is nature-destructive and unstainable. On one hand, it has led to increasing temperatures, and on the other, a degradation of ecosystems that form natural carbon sinks.

The Chambal story offers a powerful climate lesson. Most extreme weather events—from droughts to floods—are rooted in damaged water systems. Most of the climate change disasters were water related and solution to resilience to these disasters also lies in water.

TBS argues that even switching entirely to clean energy won’t build resilience without restoring rivers, aquifers, and forests. River rejuvenation leads to increase in green cover, after all, are far better carbon sinks, than carbon capture and storage (CCS) and other carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods which are mostly in their infancy.

Conclusion:

Where the Chambal once symbolised fear, it now showcases one of India’s most remarkable grassroots transformations. What moral persuasion and policing couldn’t achieve, water did—quietly, patiently, and decisively!

While moral persuasion by Sarvodaya leaders Vinoba Bhave and Jaya Prakash Narayan could only achieve partial success, Dr. Rajendra Singh proved that a change of heart of dacoits was possible. The simple expedient of making water available once again brought agricultural prosperity and weaned away bandits from a life of lawlessness. They saw hope in earning a living in a lawful way. He proved that it was not the ‘eye-for-an-eye’ tradition but the severe scarcity of water that was the curse of the Chambal that had brought it such disrepute.

It turned a landscape of banditry into a landscape of hope!