Kalyan Chatterjee interviews Dr Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, an internationally renowned professional on public interest research, mountain environment and water governance in south Asia.

Kalyan Chatterjee interviews Dr Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, an internationally renowned professional on public interest research, mountain environment and water governance in south Asia.

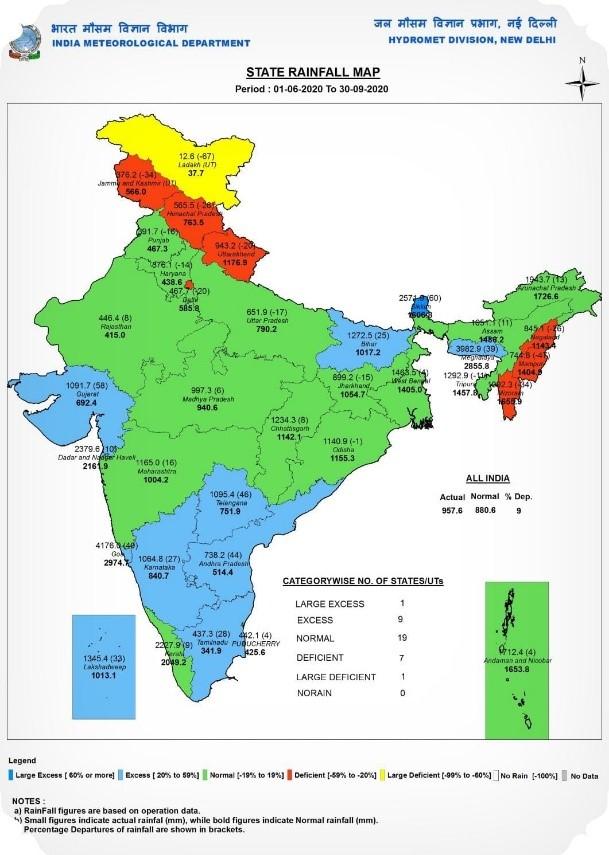

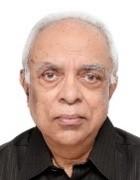

India receives an average of 120 centimetres of rainfall annually, according to the India Meteorological Department — a figure that places it among the world’s most water-abundant nations, at least in terms of volume for its landmass. Yet, paradoxically, as the summer months arrive, many of the country’s major cities are gripped by acute water shortages. India now ranks as the 24th most water-stressed country globally, according to World Population Review (WPR). Last summer offered a stark reminder, with residents in Delhi and earlier in Bengaluru queuing for hours around water tankers. What this summer holds for urban India remains uncertain, but the early signs suggest that the crisis may well deepen before it abates. Delhi and Bengaluru, however, are not isolated cases. An alarming report by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) underscores the systemic nature of the problem. Citing data from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, it notes that at least 14 other major cities — many of them state capitals — are already suffering from significant groundwater stress. The situation is expected to deteriorate further: by 2030, India’s urban water demand is projected to double the availability of raw water.

SCARCITY AMID PLENTY

This paradox of severe scarcity amid plenty is due to two factors – uneven distribution of rainfall and its concentration during the three to four monsoon months. Hydrologist Jayanta Bandyopadhyay describes this as “temporal inequity” in which heavy rain during the monsoon months causes devastating floods on the one hand while, scarcity marks the dry season on the other. To meet water needs during the lean months, when surface water flows are low, a great deal of dependence is placed on groundwater leading to severe depletion. According to NGWA, India, in fact has become the largest extractor of ground water in the world, surpassing by a large margin than the next two biggest groundwater users combined – United States and China.

Dr. Bandyopadhyay told Tatsat Chronicle: “India has reached this crisis because water resource management strategy has been guided by the philosophy that water is a strictly fixed resource and we cannot really destroy it on any significant scale. On the basis of this philosophy that water is indestructible because it is renewable, India has, in fact, extensively depleted her water resources. Disrupted water cycles can turn water from an abundant renewable resource into a vanishing non-renewable resource.”

HYDROLOGICAL DESTABILIZATION

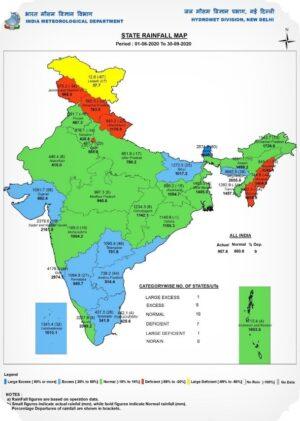

Dr. Bandyopadhyay doesn’t agree that droughts or erratic monsoons are to blame for the shortages. He said, “Fluctuations in the monsoons largely determine the incidence of drought. There are, however, many other processes which lead to the generation of water scarcity. Deforestation and destabilization of hydrological conditions in the mountain catchments can lead to drying up of rivers and streams during the post-monsoon periods because of high run-offs. In such situations ‘surface water drought’ can occur despite normal precipitation”.

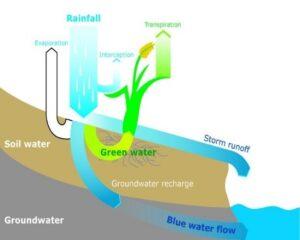

He further added, “Soils can lose their effective moisture conserving capacity through complex processes and the consequent aridization may be described as soil water drought. And this can happen despite normal rainfall and hydrologically stable catchment. While various forms of drought can be generated independently, rainwater, surface water, soil water and ground water are not ecologically separable. These systems are intricately linked in a water cycle that describes the dynamics of the continuously changing water resource. Under normal conditions streams and rivers have perineal flows derived from groundwater sources in the upper catchments, whereas groundwater in the flat plains of river basins is recharged from the surface water available from streams, lakes, and rivers”.

In Dr. Bandyopadhyay’s opinion, the problem is essentially one of governance. Dr. Bandyopadhyay said, “Separate institutions govern groundwater and surface water. While the Central Groundwater Board (CGWB) deals with only groundwater, surface water is the responsibility of Central Water Commission (CWC). But the two do not talk to each other”. He further points out that coordination between them is necessary as groundwater and rainwater that feeds surface water are linked. He feels that legal provisions have to be introduced so that like surface water, groundwater too is state-owned, and its use regulated. It might be politically difficult to achieve but can be done gradually.

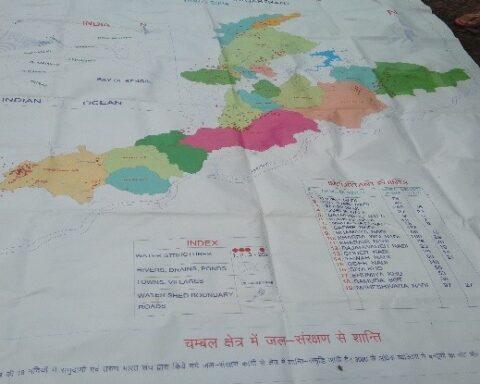

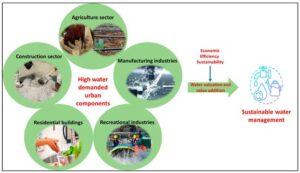

INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT

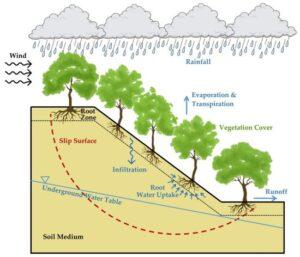

Touching upon the rapid growth in urban populations, Dr. Bandyopadhyay said, “As of now there is no control either over urban migration or over groundwater use. The only way out would be to adopt an integrated approach to water resource management. Water engineering is required to match the inequity in precipitation from the sky with equity of the demand. This needs water engineering that helps to store the water from surplus period to meet the needs of the lean season. A holistic basin-wide approach needs to be adopted since urban water scarcity cannot be treated in an isolated fashion”.

THE PROBLEM

The main problem is that India has been unable to achieve a balance between use of groundwater and the need to prevent depletion by adequate measures to systematically replenish groundwater during the period of plenty to prevent excessive dropping of the level of the water table. Between 1990 and 2014, the water table in north India fell on an average by 8 cm each year.

Dr. Bandyopadhyay’s contention is borne out by the ORF study that has found that the four cities, including Delhi and Bengaluru have seen large increases in population without corresponding major augmentation of their raw water storage capacities. The report estimated that the per capita availability of water in Delhi had shrunk from 95 cubic metres in 2001 to just a little more than half this quantity by 2011. It had reduced by more than half in all the other cities covered by the study – Bengaluru, Chennai and Coimbatore.

The factors identified for triggering this dire situation by the 2021 ORF report were rapid urbanisation and population growth, coupled with no added raw water sources, archaic water infrastructure and inefficient water governance means that most Indian cities are ill-equipped to handle the increasing water scarcity and water stress. The report, whose authors were geologist Biplob Chatterjee and ecologist Aparna Roy was published by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in 2021, and based on a comprehensive first-hand study of water supply and demand in four major water-stressed cities – Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Coimbatore.

While Bengaluru is totally dependent on groundwater, Delhi draws from both surface sources and groundwater. Delhi Jal Board’s (DJB’s) water supply is made up of 90 per cent surface water and just 10 per cent ground water. But, much of the water demand in slum areas is met by suppliers who operate private water wells. According to one study in India an estimated 340 million people depend primarily on self-supply sources and many medium-sized cities are highly dependent on private wells for domestic self-supply which can amount from 40 to 60 per cent of water supplied.

Shortages aggravated by leakages, are of the order of 20 to 45 per cent which makes it imperative for India’s urban water management system to prioritise upgrading and replacing major parts of the distribution infrastructure to plug leakages. In Delhi, for example, the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) supplies 935 million gallons of water every day to its inhabitants. Even taking the lower figure, the loss would be about 200 million gallons per day, a quantity that a water short city can hardly afford to lose. Poor water management affects the aim of reaching piped water to all residents particularly those large sections that live in slums or peri-urban areas outside the reach of the infrastructure. In Delhi alone about three million people live in slums, nearly a fifth of its population. The situation in Bengaluru is similar, while nearly a third of Chennai’s residents live in slums. They meet their water requirements from private water wells.

The ORF study said that though peri-urban areas in the four cities have been included within city limits, their urban local bodies have been slow in extending the city water infrastructure, both supply and sewage discharge management, in these areas. The water distribution network in peri-urban and slum areas have been restricted to single tap connections for a cluster of houses. Consequently, residents of these areas have been compelled to resort to large scale groundwater extraction.

Informal water vendors, sometimes described as the ‘tanker mafia’, make hay in conditions of severe scarcity by drawing groundwater in peri-urban areas to supply water to core urban areas in tankers. The tanker vendors resort to aggressive pricing and groundwater mining, even going to the extent of stealing water meant to meet agricultural needs. Groundwater mining has led to a situation in which more groundwater being extracted than is recharged during the monsoon period in Delhi, Bengaluru and Chennai. Data collected by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) shows that in all these cities groundwater overdraft reaches upto 170 per cent. This suggests that the cities are yet to establish an appropriate framework to control and manage groundwater resources.

THE SOLUTION

The simple solution offered by Dr. Bandyopadhyay “Reuse, Reduce and Recycle – the three ‘R’s that need to be followed to forestall the looming water scarcity. By reusing the same water for different purposes reducing water demand. Recycling can genuinely increase the water supply and even double it, as the same water is being used twice. Though it has been put into practice in some pockets, it is easier said than done”.

GREEN WATER CREDITS

A slightly more complex market-based solution has been offered by

Nilanjan Ghosh and Soumya Bhowmick in a report prepared by the ORF in partnership with beverage major Bisleri. The market-based approach presented in the 2025 report ‘Trading Blue Gold: A Blueprint for Water.

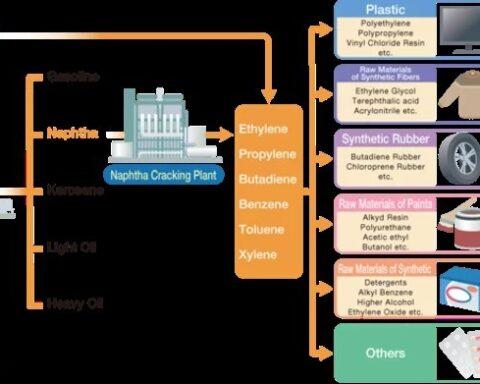

Credit Valuation in India’ is the concept of Green Water Credits (GWC) which is modelled after carbon credits. Green water is moisture held in the soil and normally represents the largest component of precipitation. It is managed by farmers and foresters and increases productive transpiration, reduces soil evaporation, controls runoff, encourages groundwater recharge and decreases flooding. GWC is a financial mechanism that supports upstream farmers to invest in improved green water management practices. To achieve this a GWC fund needs to be created by downstream private and public water use beneficiaries.

The ORF Report points out that despite its importance green water management has been neglected, as traditional water management focuses on blue water or the surface and groundwater only. The GWC framework quantifies the economic value of sustainable practices such as terraced and ridged farming that prevent runoff and encourage absorption by the soil as well as water saving practices like levelling and drip irrigation. Farmers implementing green water practices earn credits based on measurable improvements, while downstream users fund these credits in exchange for enhanced water resources. Though the authors of the ORF Report have suggested a model to calculate the dollar value of credits, there is no widely accepted models yet.

Acute water shortage is not merely a question of infrastructure. It is a failure of long-term planning, governance, and environmental stewardship. Despite decades of warnings, urban growth has far outpaced the capacity of water supply systems, and mismanagement of groundwater resources has pushed many regions to the brink. Rainwater harvesting, wastewater recycling, and sustainable urban planning has been discussed ad nauseam, yet implementation remains spotty and insufficient.

The coming summer may test not just the resilience of India’s cities, but the political will of those charged with managing them. Water is no longer just a resource — it is an existential challenge, demanding urgent, coordinated, and transparent action.

By Kalyan Chatterjee